Thirty-five years after his death, does Western Christianity have anything to learn from the Hindu who learned so much from Christ?

All the books are being reissued now, both the authorized and unauthorized biographies, many with a photo of Ben Kingsley rather than Gandhi on the cover, and a slash of color heralding “the book that inspired the epic film” or words to that effect. Mahatma Gandhi, the Great Soul, the wizened old man who through his personal force struck down an empire, is back in the news, thanks to Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi. Thirty-five years after his death, the mass media have granted a few more nanoseconds of historical time to the man who changed the landscape of the globe.

Gandhi lived life in italics. There was no one like him: no one more disciplined, or stubborn, or consistent, or creative, or baffling, or lovable, or infuriating. Many of the political principles we take for granted today, as well as the muffled sounds of protest that echo in the streets of Jaruzelski’s Poland and Pinochet’s Chile and Botha’s South Africa, originated in the mind of this man who led a fifth of humanity into the twentieth century.

Now, 35 years later, it is time to begin to assess Gandhi, his life and beliefs, by asking what relevance he has in our speeded-up world of nuclear tension, environmental carnage, and militant nationalism. And because he was a saint—a Hindu saint, certainly, but one strategically informed by Christian thinkers—we in the church must pause to ponder what message he has for us also. Gandhi died three years after America used the atom bomb, an event that convinced him more than ever that for the planet to survive the world must look to the East for solutions, not the West. The West has always looked to the East, he claimed, citing Jesus, Buddha, Moses, Zoroaster, Mohammed, Rama. The alternative he foresaw was a global cataclysm brought on by decadence, materialism, and armed conflict.

I recently spent a month in India, Gandhi’s homeland. Its prophet is honored there, even revered, but hardly followed. Giant textile mills have supplanted the wooden spinning wheels. The corruption of India’s bureaucracy is legendary. And, three bloody wars after Gandhi, his nation flirts with the ring of power that haunted Gandhi: nuclear weapons. Even so, India cannot get the strange little man out of its consciousness. Nor, as Attenborough’s film reminds us, can the rest of the world.

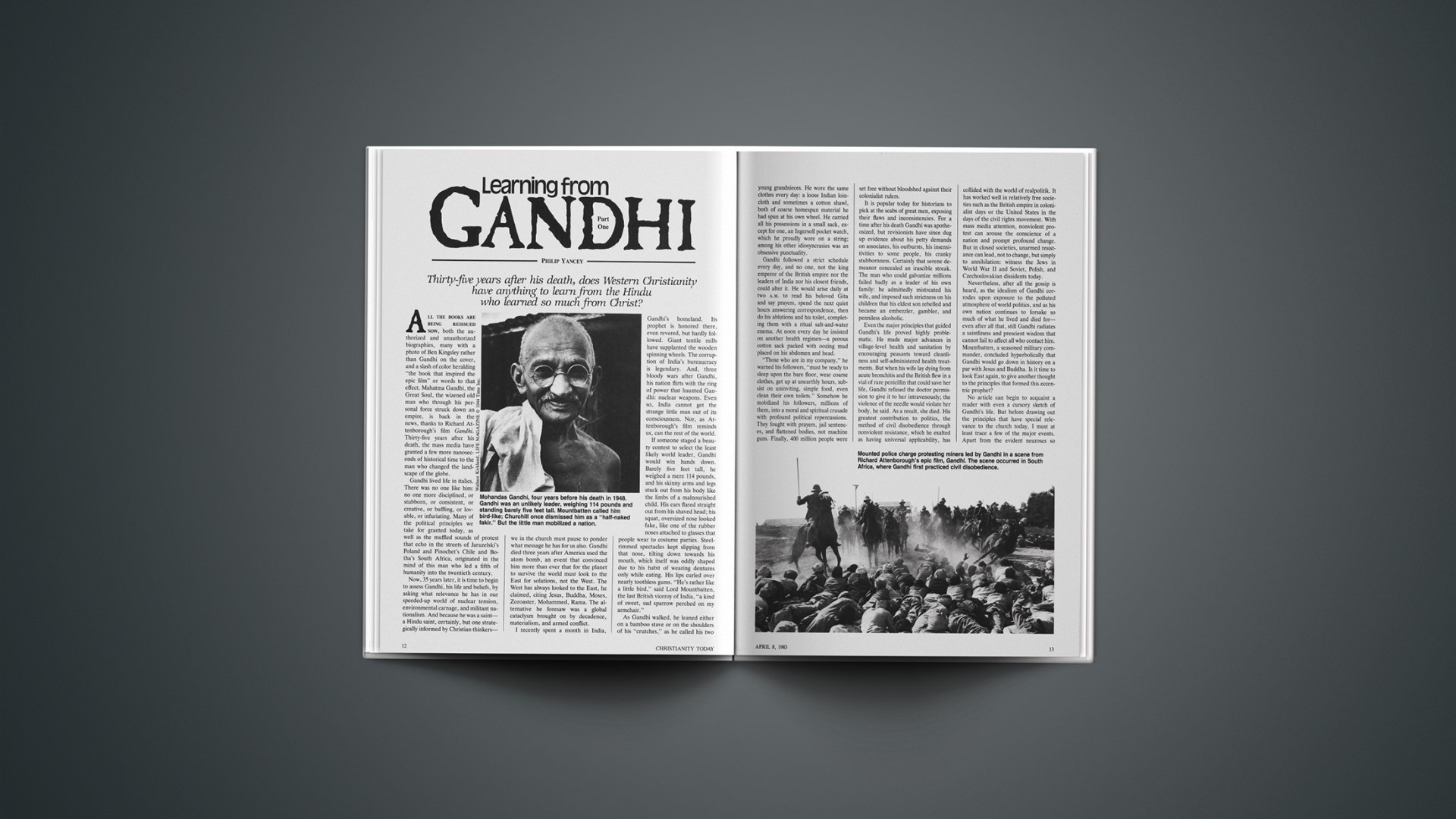

If someone staged a beauty contest to select the least likely world leader, Gandhi would win hands down. Barely five feet tall, he weighed a mere 114 pounds, and his skinny arms and legs stuck out from his body like the limbs of a malnourished child. His ears flared straight out from his shaved head; his squat, oversized nose looked fake, like one of the rubber noses attached to glasses that people wear to costume parties. Steelrimmed spectacles kept slipping from that nose, tilting down towards his mouth, which itself was oddly shaped due to his habit of wearing dentures only while eating. His lips curled over nearly toothless gums. “He’s rather like a little bird,” said Lord Mountbatten, the last British viceroy of India, “a kind of sweet, sad sparrow perched on my armchair.”

As Gandhi walked, he leaned either on a bamboo stave or on the shoulders of his “crutches,” as he called his two young grandnieces. He wore the same clothes every day: a loose Indian loincloth and sometimes a cotton shawl, both of coarse homespun material he had spun at his own wheel. He carried all his possessions in a small sack, except for one, an Ingersoll pocket watch, which he proudly wore on a string; among his other idiosyncrasies was an obsessive punctuality.

Gandhi followed a strict schedule every day, and no one, not the king emperor of the British empire nor the leaders of India nor his closest friends, could alter it. He would arise daily at two A.M. to read his beloved Gita and say prayers, spend the next quiet hours answering correspondence, then do his ablutions and his toilet, completing them with a ritual salt-and-water enema. At noon every day he insisted on another health regimen—a porous cotton sack packed with oozing mud placed on his abdomen and head.

“Those who are in my company,” he warned his followers, “must be ready to sleep upon the bare floor, wear coarse clothes, get up at unearthly hours, subsist on uninviting, simple food, even clean their own toilets.” Somehow he mobilized his followers, millions of them, into a moral and spiritual crusade with profound political repercussions. They fought with prayers, jail sentences, and flattened bodies, not machine guns. Finally, 400 million people were set free without bloodshed against their colonialist rulers.

It is popular today for historians to pick at the scabs of great men, exposing their flaws and inconsistencies. For a time after his death Gandhi was apotheosized, but revisionists have since dug up evidence about his petty demands on associates, his outbursts, his insensitivities to some people, his cranky stubbornness. Certainly that serene demeanor concealed an irascible streak. The man who could galvanize millions failed badly as a leader of his own family: he admittedly mistreated his wife, and imposed such strictness on his children that his eldest son rebelled and became an embezzler, gambler, and penniless alcoholic.

Even the major principles that guided Gandhi’s life proved highly problematic. He made major advances in village-level health and sanitation by encouraging peasants toward cleanliness and self-administered health treatments. But when his wife lay dying from acute bronchitis and the British flew in a vial of rare penicillin that could save her life, Gandhi refused the doctor permission to give it to her intravenously; the violence of the needle would violate her body, he said. As a result, she died. His greatest contribution to politics, the method of civil disobedience through nonviolent resistance, which he exalted as having universal applicability, has collided with the world of realpolitik. It has worked well in relatively free societies such as the British empire in colonialist days or the United States in the days of the civil rights movement. With mass media attention, nonviolent protest can arouse the conscience of a nation and prompt profound change. But in closed societies, unarmed resistance can lead, not to change, but simply to annihilation: witness the Jews in World War II and Soviet, Polish, and Czechoslovakian dissidents today.

Nevertheless, after all the gossip is heard, as the idealism of Gandhi corrodes upon exposure to the polluted atmosphere of world politics, and as his own nation continues to forsake so much of what he lived and died for—even after all that, still Gandhi radiates a saintliness and prescient wisdom that cannot fail to affect all who contact him. Mountbatten, a seasoned military commander, concluded hyperbolically that Gandhi would go down in history on a par with Jesus and Buddha. Is it time to look East again, to give another thought to the principles that formed this eccentric prophet?

No article can begin to acquaint a reader with even a cursory sketch of Gandhi’s life. But before drawing out the principles that have special relevance to the church today, I must at least trace a few of the major events. Apart from the evident neuroses so gleefully mined by revisionist historians, the measure of a man like Gandhi depends on his responses at hinge moments in life. Those few moments reveal Gandhi’s true greatness.

Prophets in the tradition of an Elijah or John the Baptist are not easily imagined in a modern setting. What would one look like? What would he wear? What would he say if confronted by shopping centers and nuclear bombs, if followed by an army of reporters, if asked his opinion on the inevitable civil war? Like some of those prophets but in a modern context, Gandhi offers a startling, innovative response. He redefined politics and spirituality, brought Britain to its knees, fused a nation, and changed the globe forever. Though not a Christian by belief or practice, Gandhi attempted to an impressive degree to live out some of the very same principles that characterized Jesus. His life deserves a moment’s reflection.

Protests

Gandhi’s doctrine of civil disobedience evolved gradually. In two decades in South Africa he had led marches, taken his share of beatings, spent a few hundred days in jail, and had experienced the mixed results of protest under oppressive regimes. Upon return to India he confronted a very different situation. There, his concern was not for a minority, a tightly knit Indian community in a strange land, but a majority, 400 million citizens strong, composed of diverse subcultures in a subcontinent ruled by the powerful British. As Britain started tightening the screws against Indian nationalism and protest, notably in the Rowlatt Act, Gandhi meditated long hours about the appropriate response. It came to him early one morning, in the twilight moments between sleep and consciousness. He decided to call for a day of mourning. No activity at all. India would respond with utter quietness. Shops would close, traffic would cease, the country would simply shut down for one day. Nothing like it had been attempted before in history, and we who live in its wake, after dozens of adaptations around the world, can easily miss the extraordinary genius of that response.

Gandhi devised a suitable reply to the classically colonialist system of exploitation. Britain was growing raw cotton in India, transporting it to England for milling and manufacture, and shipping the finished product back to India for sale at high prices. To break the chain, Gandhi urged every Indian, villager or city dweller, to spend at least an hour a day spinning cotton. He set the example himself, digging up an old wooden spinning wheel that he used the rest of his life.

When Britain imposed a tax on salt, a staple that every person, no matter how poor, required, Gandhi countered with his famous Salt March, a 250-mile, painstakingly slow march to Bombay. Millions of cheering peasants hailed his entourage along the way while nervous officials back in London anxiously watched every step of his snail-like progress. One man was stitching together the fabric of a nation. He arrived in Bombay, waded out into the sea, and scooped up a fistful of salt. He held it in the air like a scepter as a symbol of defiance to the empire. Let India gather her own salt, and boycott everything British. (Contrast that approach with the American colonists’ response to Britain’s stamp tax.)

Gandhi proved to be a thorn in the side of the British because orthodox means could not put down his unorthodox protests. When they hauled him into court and threatened a jail sentence, he calmly asked for the maximum sentence. Far from being a discipline, the jail environment offered more luxury than he allowed himself when free, and gave the additional benefit of extended periods of time for reflection and writing. In all, Gandhi spent 2,338 days (the equivalent of six years) in British jails. He said, “Freedom is often to be found inside a prison’s walls, even on a gallows; never in council chambers, courts, and classrooms.”

When the British tried more traditional methods of oppression—opening fire on the demonstrators—they created martyrs and only served to unite the nation further. In one notorious incident, British troops trained machine guns on a peaceful but illegal gathering, shooting 1,650 rounds and causing 1,516 casualties.

Later in his life, Gandhi’s inner voice led him to the most devastating tactic of protest, a tactic that sealed the fate of the empire and eventually was to save the new nation from anarchy. He simply fasted, depriving himself of food. Gandhi planned his fasts as carefully as a general plans military strategy. Sometimes he set them for specified lengths of time, such as 21 days, and sometimes he announced a fast unto death unless certain demands were met. The ironies defy comprehension: an ultimate weapon of intentional starvation within a nation of starving masses, a single man’s self-sacrifice as the most potent force in defeating the most widespread empire in history.

Against all odds, the tactics worked. Churchill had foamed at “the nauseating and humiliating spectacle of this one-time Inner Temple lawyer, now seditious fakir, striding half-naked up the steps of the viceroy’s palace, there to negotiate and parley on equal terms with the representative of the king emperor.” But Gandhi became Mahatma, the Great Soul. He guaranteed morality with his own life: no one was willing to risk responsibility for letting the Great Soul die. One by one, the generals, viceroys, prime ministers, and finally the king yielded to the demands of “that half-naked fakir.”

Untouchables

When Gandhi lived in India, one-sixth of the population comprised a group of people who seemed more animal than human. They lived in dark, putrid slums, amid open sewers in which swarmed rats and every other disease-bearing agent. Thousands of years before, a Hindu ruler had devised the caste system as a means of keeping the darker Dravidians in utter subjection to the ruling Aryans, and his success surpassed that of any comparable form of slavery. The Hindu doctrine of Karma gave a theological basis for the elaborate system of 5,000 subcastes, and the lowest caste of all, the Untouchables, did not dare protest. Until Gandhi, no one had taken up their cause.

You could tell Untouchables by their dark color and by their posture, for they cringed like beaten animals. The name defined them—if a caste Hindu so much as touched one, or touched a drop of water one had polluted, he would shriek away and begin an elaborate purification process. An Untouchable had to shrink from the path of a caste Hindu to avoid casting a shadow and thus defiling him. Some parts of India allowed Untouchables to leave their shacks only at night; there, they were known as the Invisibles. Untouchables gave a valuable service to society; they swept the streets and cleaned the latrines and sewers, acts a caste Hindu would never perform.

With nothing to gain but abuse and rejection from the rest of his peers, Mahatma Gandhi took up the cause of the Untouchables. In a singularly brilliant stroke, he bestowed on them a new name; they were no longer to be called Untouchables, but rather Harijans, the Children of God. At his first ashram (a commune), Gandhi stirred up a storm of protest by inviting an Untouchable to move in with him and the others. When the chief financial backer of the commune experiment withdrew his support, Gandhi made plans to move to the Harijans’ own quarters. Finally he committed the most defiling act possible for a Hindu to perform: he cleaned the latrines of the Untouchables. Back in India he adopted them as his brothers and stayed in their hovels in Calcutta whenever possible.

Years later, after independence, when all other leaders in India pressed Lord Mountbatten to accept the honorary post of governor-general, Gandhi proposed his own alternative candidate: an Untouchable sweeper girl “of stout heart, incorruptible and crystal-like in her purity.” His candidate did not get the nomination, of course, but by such symbolic actions Gandhi indelibly changed the perception of Untouchability all across India. Laws were changed and strictures removed. Social ostracism gradually melted. And today, all over India, 100 million people now identify themselves not by a curse but by a blessing—they are the Children of God.

Gandhi And Christianity

Gandhi never called himself a Christian and was never seriously tempted to become one, but he was a devout admirer of Jesus Christ. Each evening at seven he would conduct a prayer meeting which became the forum for most of his important thoughts. Sometimes he would simply stand, read the Sermon on the Mount, and sit down. He credited Christianity for two of his most significant guiding principles: nonviolence and simple living. But he had often seen the disparity between Christ and Christians. He said, “Stoning prophets and erecting churches to their memory afterwards has been the way of the world through the ages. Today we worship Christ, but the Christ in the flesh we crucified.”

Growing up in India, Gandhi had little contact with Christians as a youngster. Rumors spread in his town that if a Hindu converted to Christianity he would be forced to eat meat, drink hard liquor, and wear European clothes. Gandhi recalls one very distasteful memory of a Christian missionary on the street corner of his town pouring abuse on the Hindu gods.

As a law student in England, Gandhi had a more prolonged exposure to Christianity. Out of obligation to a friend, he read through the entire Bible. He admits that the Old Testament was uninspiring and put him to sleep, especially the book of Numbers. But the New Testament produced a profound impression. Throughout his life, Gandhi found himself going back to the teachings of Jesus.

Gandhi lived in South Africa during the most formative period of his life, and a few nasty incidents there did little to disabuse him of his notions of Christianity. He encountered blatant discrimination in that ostensibly Christian society, being thrown off trains, excluded from hotels and restaurants, and made to feel unwelcome even in some Christian gatherings.

One white woman who used to invite Gandhi for Sunday meals made it clear that he was unwelcome when she saw the influence Gandhi’s strict vegetarianism was having on her five-year-old son. Before that incident, he had attended the Wesleyan church with her family every Sunday. “The church did not make a favorable impression on me,” he concludes laconically, citing uninspiring sermons and a congregation who “appeared rather to be worldly-minded, people going to church for recreation and in conformity to custom.”

Yet while in South Africa Gandhi made a thorough study of comparative religions. He cites two books by Christian authors (Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You and Ruskin’s Unto this Last) as two of the three most influential books in his life. The third was the Bible. He read Pearson’s Many Infallible Proofs (which “had no effect on me”) and Butler’s The Analogy of Religion among a host of other Christian books and commentaries.

In his autobiography, Gandhi recounts several episodes of Christians attempting to convert him. One kindly man even went so far as to take him to the Wellington Convention, a revival-type service similar to Keswick conventions. Andrew Murray spoke, and Gandhi was quite impressed by stories he told about George Müller’s faith. This is how Gandhi recalls the convention and summarizes his difficulties with Christianity: “Mr. Baker was hard put to it in having a ‘coloured man’ like me for his companion. He had to suffer inconveniences on many occasions entirely on account of me. We had to break the journey on the way, as one of the days happened to be a Sunday, and Mr. Baker and his party would not travel on the sabbath.…

“This Convention was an assemblage of devout Christians. I was delighted at their faith. I met the Rev. Murray. I saw that many were praying for me. I liked some of their hymns, they were very sweet.

“The Convention lasted for three days. I could understand and appreciate the devoutness of those who attended it. But I saw no reason for changing my belief—my religion. It was impossible for me to believe that I could go to heaven or attain salvation only by becoming a Christian. When I frankly said so to some of the good Christian friends, they were shocked. But there was no help for it.

“My difficulties lay deeper. It was more than I could believe that Jesus was the only incarnate son of God, and that only he who believed in him would have everlasting life. If God could have sons, all of us were His sons. If Jesus was like God, or God Himself, then all men were like God and could be God Himself. My reason was not ready to believe literally that Jesus by his death and by his blood redeemed the sins of the world. Metaphorically there might be some truth in it. Again, according to Christianity only human beings had souls, and not other living beings, for whom death meant complete extinction; while I held a contrary belief. I could accept Jesus as a martyr, an embodiment of sacrifice, and a divine teacher, but not as the most perfect man ever born. His death on the Cross was a great example to the world, but that there was anything like a mysterious or miraculous virtue in it my heart could not accept. The pious lives of Christians did not give my anything that the lives of men of other faiths had failed to give. I had seen in other lives just the same reformation that I had heard of among Christians. Philosophically there was nothing extraordinary in Christian principles. From the point of view of sacrifice, it seemed to me that the Hindus greatly surpassed the Christians. It was impossible for me to regard Christianity as a perfect religion or the greatest of all religions.

“I shared this mental churning with my Christian friends whenever there was an opportunity, but their answers could not satisfy me.”

Gandhi graciously omits from his autobiography one more painful experience that occurred in South Africa. The Indian community especially admired a Christian named C. F. Andrews whom they themselves nicknamed “Christ’s Faithful Apostle.” Having heard so much about Andrews, Gandhi sought to hear him. But when C. F. Andrews was invited to speak in a church in South Africa, Gandhi was barred from the meeting—his skin color was not white.

Commenting on Gandhi’s experiences in South Africa, E. Stanley Jones concludes, “Racialism has many sins to bear, but perhaps its worst sin was the obscuring of Christ in an hour when one of the greatest souls born of a woman was making his decision.”

—Philip Yancey

India’S Ointment

As the momentum for independence swept across India and its citizens realized they were going to get their country back at last, centuries-old animosities began to boil to the surface. In sudden spasms of violence, Hindus and Moslems turned on each other with ferocity on a scale without historical precedent. Moslems in the Bengal and Noakhali districts burned the huts of their Hindu neighbors, forced them to eat sacred cows, raped the Hindu women, and butchered their husbands. Hindus fought back with a vengeance, and thousands of Indians died in the months leading up to independence. Increasingly it appeared that the whole country would explode in flames. In New Delhi, Congress party leaders met anxiously with British and Moslem officials to try to work out some compromise. Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the Moslem leader, stood firm against compromise. To him, the Hindu-controlled Congress party had already proven itself untrustworthy by excluding Moslems from power. He and 100 million Moslems were demanding a separate country called Pakistan. But Congress leaders, most notably Gandhi, saw partition as a terrible blow to their dream of a unified India. In an emotional appeal, Gandhi cried out that his own body would be broken before he could ever allow Mother India to break in two. The debates went on, and so did the rapine.

Gandhi proposed his own solution with total sincerity. In order to avoid partition, he suggested, the Congress party should turn over all the government to the Moslems, the Hindus thus voluntarily subjecting themselves to a Moslem minority one-third their size. Not everyone was up to his ideals; the Congress leadership permanently broke with Gandhi, and a separate Pakistan became inevitable.

While the officials sat in elegant palace rooms and bartered for power and land, Gandhi headed out on an “ointment” crusade. Let them argue, he said—he was going back to the people, to the angry hordes that were assailing each other so viciously. At the age of 77, he headed to the Noakhali region where the most violence had occurred, and roamed among the charred villages. He simply wanted to be there, he said, to absorb their pain and to hold prayer meetings for the love and brotherhood that he cherished. Though a Hindu, he led his ragtag group into Moslem villages to face their taunts and rocks and bottles. When he approached a village, the most famous Asian alive would beg for shelter and live on the charity of the villagers. If turned away, he would look for a tree to sleep under. If accepted, he would read from the Gita and Koran and New Testament, teach simple principles of health and hygiene, then trudge on to the next village. In all, he visited 47 villages, walking 116 miles on bruised and aching bare feet.

In each village Gandhi tried to persuade one Hindu and one Moslem leader to move into the same house together and serve as guarantors of peace. He asked them to pledge themselves to fast unto death if one from their own religion attacked an enemy. Incredibly, the method worked. While debates continued in the Delhi palaces, Gandhi’s personal ointment began to palliate the open wounds across that state and nation. For awhile the killing stopped.

Soul Force

After independence, however, India needed more than ointment; she needed huge swaths of gauze bandages to stanch the flow of blood that quite literally turned her rivers red and filled her skies with vultures. As Gandhi had predicted in his eloquent appeals against partition, independence ushered in a holocaust of death and destruction such as the world had never seen. When the boundary lines were finally announced, millions of Hindus found themselves islanded within the borders of a newly created and hostile Pakistan, and millions of Moslems found themselves in Hindu India. Thus began the greatest mass migration in human history. In all, 10 million people left their homes and attempted a frenzied march across searing plains to a new home.

Lord Mountbatten, the British viceroy who oversaw independence, knew that two areas were potential conflagrations. On the west where India bordered West Pakistan, the scene of the largest migration, hostilities would undoubtedly erupt. But the east, along the gerrymandered border of East Pakistan, threatened even greater danger. Sitting beside that border was the most violent city in Asia, Kipling’s City of Dreadful Night—Calcutta. No city in the world matched its squalor, its pullulating masses (more than 400,000 beggars), its religious bigotry, its unrestrained passions. Calcutta brazenly worshiped the Hindu deity Kali, the Goddess of Destruction. Months before, as a one-day preview of what was to come, violence had erupted in Calcutta. On that day, known as the Great Calcutta Killings, 6,000 Hindu and Moslem bodies were tossed in the Hooghly River, stuffed in gutters or left to lie in streets. Most had been beaten or trampled to death.

Mountbatten had to respond first to the western frontier as reports of atrocities came flooding over the telegraph wires. Ultimately, as many as 500,000 people were to die on that frontier. Mountbatten had no choice but to send his Boundary Force, 55,000 of the most dependable British and Gurkha army troops. But that left him no reserves for the eastern front. In total desperation, Mountbatten pled with the Great Soul, Gandhi, to go to Calcutta and there, among the Untouchables he had embraced as brothers, somehow to work a miracle. Gandhi firmly declined, for he had pledged to spend the time around independence spinning, fasting, and praying with the beleaguered Hindu minority in Noakhali.

This time, Gandhi was led to change his mind, on the eve of his departure to Noakhali. He was convinced not by Mountbatten, but a Moslem leader who came personally from Calcutta to beg Gandhi to come to his city. The man, Suhrawardy, was one of the most corrupt politicians in Calcutta, and was widely believed responsible for inciting his Moslem League followers to much of the violence on the day of the Great Calcutta Killings. Now he feared for the life of every Moslem in Calcutta, and for the very survival of the city. The desperate Suhrawardy admitted only Gandhi could ward off disaster.

Gandhi listened, reconsidered, and came up with two conditions for his going to Calcutta. First, Suhrawardy must pledge that the Moslems of Noakhali (where Gandhi had been headed) would not kill a single Hindu. If the pledge was broken, Gandhi would fast to death. In effect, Gandhi was placing his own life in Suhrawardy’s hands.

The second condition was appalling to Suhrawardy, known for his decadent, luxurious lifestyle. Gandhi proposed that he and Suhrawardy live together day and night, without arms, in the heart of one of Calcutta’s worst slums. Suhrawardy swallowed hard and reluctantly agreed to accept Gandhi’s two conditions.

So it was that two days before India’s independence Mohandas Gandhi arrived in the City of Dreadful Night. A massive crowd of Indians awaited him as usual, but this one, unlike so many others, greeted him not with cheers but with shrieks of hatred and anger. They were Hindus out for revenge, and to them Gandhi represented a meek submission to the injustices Moslems had already wreaked. Many of them had seen relatives slaughtered and wives and daughters defiled by Moslem mobs. Gandhi got out of his car amid a shower of rocks and bottles. Raising one hand in a frail gesture of peace, the 77-year-old man walked alone into the crowd. “You wish to do me ill,” he called, “and so I am coming to you.” The crowd fell silent. “I have come here to serve Hindus and Moslems alike. I am going to place myself under your protection. You are welcome to turn against me if you wish. I have nearly reached the end of life’s journey. I have not much further to go. But if you again go mad, I will not be a living witness to it.”

Peace reigned in Calcutta that day, and then Independence Day, and the next, and the next, for 16 days in all. Huge throngs gathered each evening, not as mobs bent on violence but as a congregation at Gandhi’s prayer meetings. At first a thousand came, then 10 thousand, and finally a million people jammed the streets of Gandhi’s slum to hear him lecture on peace and love and brotherhood. Once again Gandhi was confronting a political crisis with what he called “soul force,” the innate power of human spirituality.

While whole states in India were going up in flames, with millions of people fleeing their homes and thousands dying in the process, not one act of violence occurred in that most violent city. “The miracle of Calcutta,” it was called worldwide. Lord Mountbatten wrote in grateful tribute, “In the Punjab we have 55,000 soldiers and large-scale rioting on our hands. In Bengal, our force consists of one man and there is no rioting.” My “One Man Boundary Force,” he called Gandhi.

Nevertheless, the miracle did not endure. On the seventeenth day two Moslems were murdered, then a rumor spread about a Hindu victim, and before long, a few hundred yards from Gandhi’s house, a grenade was lobbed into a bus full of Moslems. The people had broken their pledge; Gandhi was to keep his. He began a fast unto death, this one not against the British but against his own countrymen. He would not eat food again unless he received repentance from all those who had committed violence and solemn vows that no more would occur.

At first no one cared. What was the life of one shriveled old man in the face of an assault on one’s religion, family, and honor? Revenge seemed far more appropriate than forgiveness. Gunfire echoed through the streets of Calcutta all during the first day of Gandhi’s fast. But within a day his already weak heart started missing one beat in four, and his blood pressure dropped precariously. The next day, as his vital signs plummeted toward death, rioters paused and began listening to reports of the old man’s blood pressure and heart rate and the analysis of his urine. The Great Soul was having an effect. Soon the attention of every citizen of Calcutta was riveted on the straw pallet where Gandhi lay, too weak to speak. The violence stopped. No one was willing to take an action that might allow the Great Soul to die.

One day more and the gang responsible for the brutal murders came to confess to Gandhi, to plead forgiveness, and to lay their arms at his feet. A truck arrived at his house filled with guns, grenades, and other weapons that people had turned in voluntarily. The leaders of every religious group in the city agreed on a declaration guaranteeing that no more killing would take place.

Convinced of their sincerity, Gandhi took his first few sips of orange juice and said his prayers. This time the miracle held. Calcutta was safe. As for Gandhi, as soon as he regained strength he made plans to head west, into the heart of the violence that had killed half a million people.