Hebrew-speaking Christian leaders in Israel speak up.

“There’s a widespread consensus in Israel that to be Jewish [a very diverse phenomenon in modern Israel] is at the very least to be non-Christian.”

This observation was made from the podium at a recent national conference of Hebrew-speaking Christian leaders in Israel, where the subject of Jewish identity came up repeatedly. Admittedly, relatively few Jews are hostile to Christians as such. Yet they are generally convinced that while Christianity may be a proper enough state for Gentiles it is inconceivable for Jews. A witty journalist doing a rather sarcastic piece on missions in Israel and Hebrew Christians some years ago remarked that the latter term made as much sense as a “drunken teetotaler” or a “white Negro.”

Of course, Hebrew-speaking Christians soften the semantic clash by reverting to the semitic root behind the Greek word Christianos (follower of Christos or the Messiah). They call themselves Yehudim Meshihiim, which literally means “Jewish Messianists.” The term “Messianist” was used by the great nineteenth-century Christian scholar Franz Delitzsch, whose translation of the New Testament into Hebrew is still in wide use among Hebrew readers.

Hebrew Christianity as a distinct movement within the body of Christ may be traced back to the roots of the church. Its witness was clearly divided between circumcised and Gentiles (Gal. 2:7–9), with circumcised Christians maintaining their life and witness among the wider Jewish people (Acts 21:20–26). Paul’s concept of the unity of Jew and Gentile in the body of Christ (Eph. 2:11–22) was designed to break down “the dividing wall of hostility,” but certainly not to cause the distinctive elements within that unity to disintegrate.

With the passage of time, one of history’s strangest conspiracies developed. The later synagogue and the triumphant church combined to suppress any possibility for continued Jewish life within the context of Christian faith. The synagogue totally banished the Hebrew Christian, declaring him outcast and dead to Israel; the church assured him that he was no longer a Jew and even forbade him to practice anything that might remind him of his Jewish identity.

Only within the past century and a half have church and synagogue been weakened sufficiently in their respective communities to permit a resurgence of a movement as radically dissenting as Hebrew Christianity. In this period it has not had to face the dire consequences that religious establishments—Jewish and Christian—were once able to impose on dissenters. While until fairly recently Hebrew Christians have been given scant recognition even by acknowledgment of their presence, little could be done to prevent them from functioning as a splinter community within free, pluralistic Hebrew and Christian societies.

Modern Zionism provided an even stronger impetus to the Hebrew Christian movement. Jewish sociologist B. Z. Sobel, in his study of Hebrew Christianity (which he sardonically dubbed “the thirteenth tribe”), said: “Hebrew Christianity began to achieve stability and organizational sophistication at about the same period in history that witnessed the emergence and phenomenal growth of political Zionism as a force among the Jews of the Western world.”

Zionism stressed the peoplehood of the Jews, with religious belief and affiliation quite optional. Many of the early Zionists (like some of their contemporary successors) vigorously rejected the religious option in favor of modern rationalist ideologies. By the force of logic, some secular Zionists were compelled to acknowledge the right of Jews to be not only agnostics but even adherents of religious beliefs outside mainstream Judaism.

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew and a pioneer Zionist, openly called upon Hebrew Christians to join the movement of return to Zion alongside their Orthodox and secularist brethren. Nevertheless, a hitch developed some 60 years later when a Polish Hebrew Carmelite monk put the matter to a formal test in the young Jewish state. At issue was his right to be a citizen of Israel as a Jew ethnically, but as a Catholic by religion. In a majority decision, the Israeli High Court ruled against him. They explained that the average Jew could not accept that a convert to another religion remained a Jew under the terms of Israeli immigrant law, or that a separation could be made between Jewish ethnicity and Jewish religion.

A subsequent case by an American Jewess, Eileen Dorflinger, put the issue in terms somewhat less stark than Hebrew Catholicism. She denied that she was a member of another religion since her beliefs were Jewish in source and content. In a brief filed with the court, she cited copiously from the Old and New Testaments to prove the Jewishness of her faith in Yeshua (Jesus). Her case also foundered when the judges ruled that Israeli immigration law did not grant automatic citizenship to members of a religion other than Judaism. (They might seek naturalization without conversion to Judaism.) The court concluded that purely by Christian standards her beliefs were in accord with the Christian religion. Nevertheless, both she and the Hebrew Catholic monk have remained in the country to this day, although they are registered as non-Jewish residents.

The bulk of Israel’s resident Hebrew Christians are either native to the country or have come to faith after arriving in Israel. Some were Hebrew Christian immigrants whose claim to being Jewish was not challenged by the officials they dealt with. A few who have been challenged have been granted permanent residence under a different law from the one applying to most Jewish immigrants. A few have been denied admission or the right of residence, sometimes on the suspicion that they were engaged in missionary activity.

In itself missionary activity is by no means illegal in Israel, but the authorities do what they can to control the flow of missionaries into the country. And Hebrew-Christian missionaries are not their first preference. A few have legally operated in the country as members of recognized missionary societies. (Of course, they are classed as Christians, not Hebrews.) Nevertheless, several years ago Hebrew members of a British missionary society in Israel applied for permanent residence, and were granted it upon presentation of proof of their Jewish origin. One, a young woman physician, was even asked to serve in the Israel Defence Forces alongside others of her profession and age group. A Hebrew-Christian colleague of hers continues to do his annual reserve duty, as do most resident Hebrew Christians.

Christian critics of Israel often point to the dilemma of Hebrew Christians in Israel as evidence of things unproven in someone else’s prophetic end-time scheme. “A Christian Hebrew is such an anomaly in the eyes of the State of Israel that he or she is not recognized as a bona fide Jew,” Mark Hanna has written in CHRISTIANITY TODAY, to bolster his thesis that “Israel today is not the people of God” (cr, Jan. 22, 1982, p. 17).

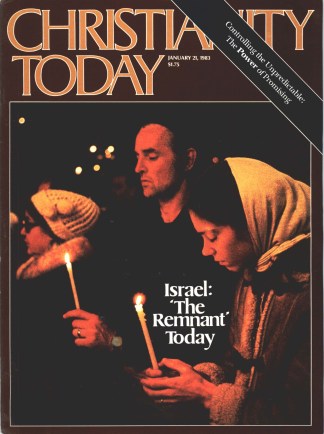

Oddly enough, Israeli Hebrew Christians would more likely come to a different conclusion. Several hundred Israeli Hebrews from the Galilee to the Negev live, worship, and witness openly to their faith in Christ within Israeli society. This is for them sufficient proof that the apostle Paul’s teaching about the remnant in Israel still applies.

It will be recalled that the apostle made an analogy between the 7,000 who had not bowed the knee to Baal of Elijah’s generation and the Hebrew Christians of his own day (Romans 11:1–4). Modern Israeli Hebrew Christians see themselves as part of that same remnant within Israel. It is true that they may have even less mainstream recognition than Elijah’s 7,000 or Paul’s larger community (Acts 21:20 speaks of thousands of Hebrew Christians in Palestine). But they are still living proof that “God has not cast off his people whom he foreknew” (Romans 11:2).

Meanwhile, a generation of “Jewish Messianists,” to use their preferred term, is growing up in the Jewish national homeland. Small, mainly fringe zealot groups do harass them from time to time, and mass media coverage can be biased, although by no means is this always true. In the wake of zealot attacks upon them, Hebrew Christians have been given opportunities to present their “case” before a national public on radio, TV, and in some of the Hebrew newspapers. Nevertheless, social and family pressures can be psychologically intense. But Hebrew Christians continue to create new forms of Hebrew worship, literature, fellowship, and congregational structures within the life of contemporary Israel.

Hebrew Christians are still heavily influenced and divided by “the two and seventy jarring sects” of Christendom, who have carried their diversified practices and creeds into the intense and fluid Israeli context. Israeli Yehudim Meshihiim are still a good distance away from the point where they may declare in anything like a common voice, “We are the Israeli church of the circumcision within the body of Christ.” All the congregations in Israel have both Jewish and Gentile members, but there are ongoing efforts to create noncongregational frameworks in which Jewish believers in Jesus living within a predominantly Jewish society can corporately tackle their specific problems.

Hebrew Christians today are engaged in what one leader described as a “two-pronged protest”—to the church, which has resisted their Jewishness within the body of Christ, and to Israel, which has resisted their Messianic faith within the body of the Jewish people. Two-front battles, even spiritual ones, are never easy to wage. In the midst of the fray it would be well for both the church and Israel to heed the counsel of Rabbi Gamaliel—still good counsel in Jerusalem today, as elsewhere: “For if their purpose or activity is of human origin, it will fail. But if it is from God, you will not be able to stop these men; you will only find yourselves fighting against God” (Acts 5:38–39, NIV).