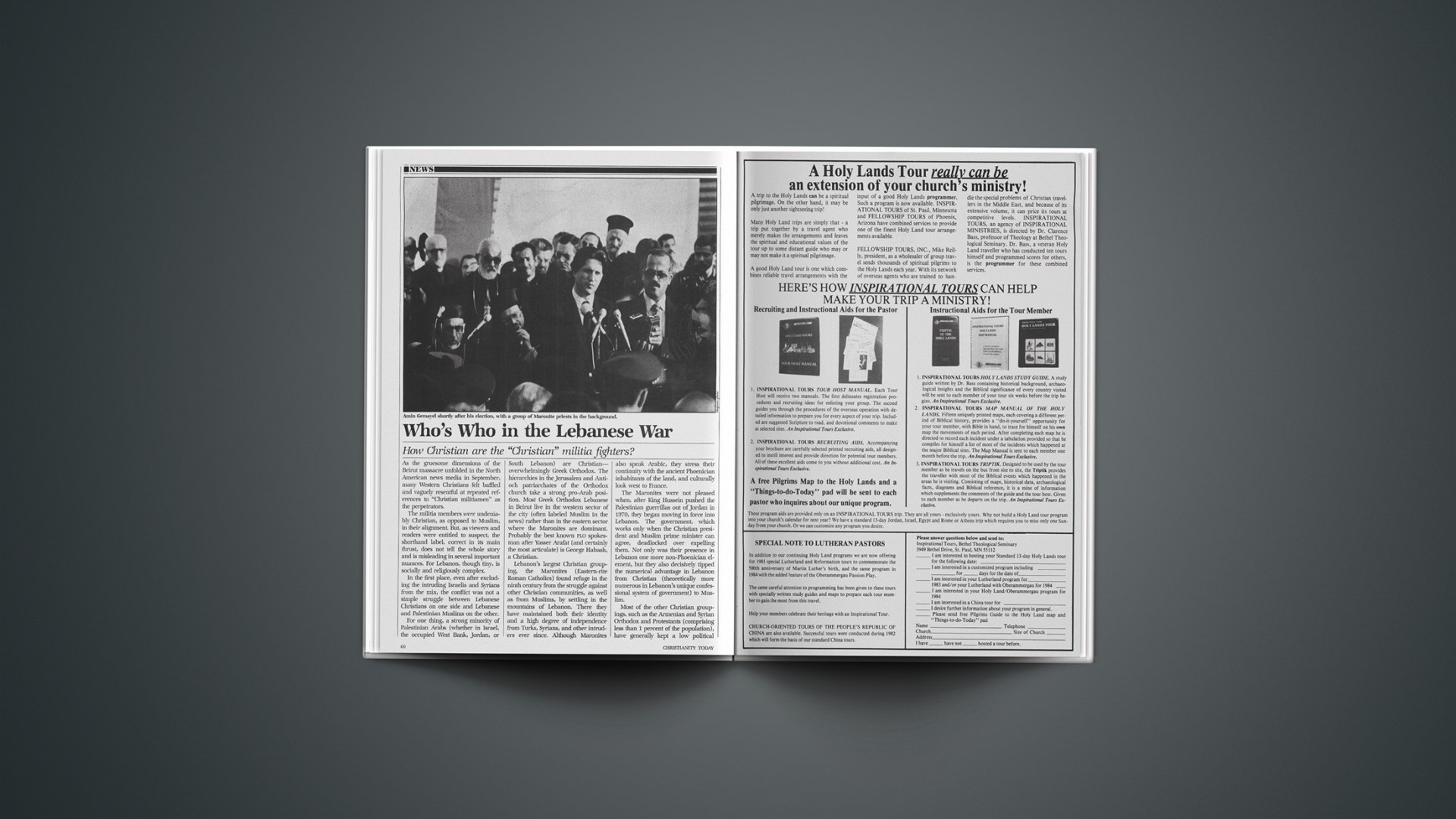

How Christian are the “Christian” militia fighters?

As the gruesome dimensions of the Beirut massacre unfolded in the North American news media in September, many Western Christians felt baffled and vaguely resentful at repeated references to “Christian militiamen” as the perpetrators.

The militia members were undeniably Christian, as opposed to Muslim, in their alignment. But, as viewers and readers were entitled to suspect, the shorthand label, correct in its main thrust, does not tell the whole story and is misleading in several important nuances. For Lebanon, though tiny, is socially and religiously complex.

In the first place, even after excluding the intruding Israelis and Syrians from the mix, the conflict was not a simple struggle between Lebanese Christians on one side and Lebanese and Palestinian Muslims on the other.

For one thing, a strong minority of Palestinian Arabs (whether in Israel, the occupied West Bank, Jordan, or South Lebanon) are Christian—overwhelmingly Greek Orthodox. The hierarchies in the Jerusalem and Antioch patriarchates of the Orthodox church take a strong pro-Arab position. Most Greek Orthodox Lebanese in Beirut live in the western sector of the city (often labeled Muslim in the news) rather than in the eastern sector where the Maronites are dominant. Probably the best known PLO spokesman after Yasser Arafat (and certainly the most articulate) is George Habash, a Christian.

Lebanon’s largest Christian grouping, the Maronites (Eastern-rite Roman Catholics) found refuge in the ninth century from the struggle against other Christian communities, as well as from Muslims, by settling in the mountains of Lebanon. There they have maintained both their identity and a high degree of independence from Turks, Syrians, and other intruders ever since. Although Maronites also speak Arabic, they stress their continuity with the ancient Phoenician inhabitants of the land, and culturally look west to France.

The Maronites were not pleased when, after King Hussein pushed the Palestinian guerrillas out of Jordan in 1970, they began moving in force into Lebanon. The government, which works only when the Christian president and Muslim prime minister can agree, deadlocked over expelling them. Not only was their presence in Lebanon one more non-Phoenician element, but they also decisively tipped the numerical advantage in Lebanon from Christian (theoretically more numerous in Lebanon’s unique confessional system of government) to Muslim.

Most of the other Christian groupings, such as the Armenian and Syrian Orthodox and Protestants (comprising less than 1 percent of the population), have generally kept a low political profile in the conflict.

Protestant leaders strive valiantly to teach that Christian faith is an individual commitment and not an inherited characteristic. But the Lebanese confessional system of government militates against them. In a country whose parliamentary seats are allotted by religious affiliation, each person’s religion is specified from birth and, as he reaches adulthood, it is attested by his identity card. Unavoidably, conversion is regarded as a political as well as a religious act.

Christians of the Middle East contrast with their Muslim neighbors in many respects, but both groups place a high priority on family and community honor. In both, for instance, the “crime of honor” of killing a daughter or sister for having indulged in premarital sex in order to cleanse the family name is tacitly condoned, and would receive a light sentence if prosecuted by authorities. It is universally presumed that a slain person will be avenged by his next of kin when the opportunity presents itself. This folk ethic is not encouraged by the churches, but neither is it vigorously combated.

In this environment, blood feuds flare up sporadically over generations. Given that background of bloodshed, it is not hard to see how vicious murders, such as those at the refugee camps, could occur.

If, as is now believed, the massacre was carried out by a maverick or rogue detachment of the Phalange militia, what is the tie to Christianity of that organization and of Lebanon’s new president who is a product of it?

The Phalange is a right-wing political party and paramilitary organization. It is the most prominent political manifestation of the Maronite community. While most Phalangists are Maronites, many Maronites are not Phalangists. There are more moderate groupings and a couple of even more nationalistic groups. The Maronite patriarch, Antonius Butros Khraish, is frequently called on to referee among these factions within his own community.

The Phalangist party is the family-run entity of the Gemayels. Pierre, in his late seventies, is an elder in the Maronite church. He became enamored of the fascist regimes prior to World War II, visiting Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy in 1936. The Phalangist title is borrowed from Franco Spain (the party’s Arabic name, Kta’eb, translates roughly as vigilantes). The militia was patterned after Nazi “brown shirt” militia.

Pierre groomed his Jesuit-trained elder son, Amin, to be his successor as party chief. But when order broke down in the bitter 1975–76 civil war, power shifted to an array of armed militias. Amin’s younger brother, Bashir, the ruthless commander of the 20,000-man Phalangist militia, soon eclipsed him. Bashir used U.S.-made weapons obtained through Israel during the civil war to level the only refugee camp in East Beirut, Tel el-Zaatar, killing 3,000 Palestinians. After his election to be president, Bashir attempted to moderate his image, but died by the kind of violence he had dispensed so efficiently.

Amin, by contrast, is a lawyer who has served in parliament for the last 10 years. A moderate, he has maintained links with the diverse groups of Lebanon. Considered softer then his iron-willed brother, it was not clear that the allegiance of all Bashir’s troops was transferred to Amin upon Bashir’s assassination.

Militia contingents bent on avenging Bashir’s death, which did not consider themselves accountable to Amin (including some 900 from the Damour battalion dedicated to avenging the Damour massacre), probably carried out the massacre in the Shatila and Sabra refugee camps.

Ironically, while Israelis pressed for an investigation, Lebanese, including the Muslim leaders, sought to avoid one. Weary of years of turmoil, they would rather not pinpoint the culprits if that would wreck the fragile, emerging basis for a consensus government under a Phalangist president who, like his trigger-happy brother before him, is an elder in the Maronite church.

Christian Colleges Win Federal Humanities Grant

The Christian College Coalition has received a $125,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The money will be used for ten regional humanities workshops for professors from its 67 member colleges.

The workshops are to encourage faculty to integrate their faith and academic field, develop new courses, new teaching strategies, and increase their publishing. Professors of the humanities from noncoalition colleges will be able to participate as well, although coalition faculty have priority and workshops will be limited to 15 faculty each.

Kenneth Shipps, dean of faculty at Barrington (Rhode Island) College, will direct the workshops. He is one of only five coalition faculty members to receive NEH grants in the past five years. He calls this grant important because “Christianity has shaped our values, lives, and literature and has been shortchanged in secular institutions and foundation grants. It’s a way of stating through federal support that Christianity has shaped these things and is worthy of exploring.”

The grant is the first government money the coalition has received, and it lends significant academic prestige to participating schools. Blanche Premo at NEH said the grant amount is slightly above average in its category of Higher Education Regional and National Grants. Of 100 applications in this category each year, 30 grants of about $100,000 each are awarded.

NEH is a free-standing federal agency dispensing tax dollars but not tied to any executive branch department.

Premo said the possibility of a court challenge based on church and state separation was thoroughly explored by NEH legal counsel and dismissed as insupportable. “The activities proposed are good, scholarly activities. Their Christian commitment will not interfere with that.”

The coalition, based in Washington, D.C., operates as an association for accredited, four-year liberal arts colleges that are distinctively Christian. Coalition president John Dellenback sees the program as a way to strengthen humanities curricula on campuses, as well as a chance for teachers to “enlarge their understanding of the Christian faith by relating it to the humanities.”

Topics for the ten workshops cover the impact of Christianity on literary theory, the arts, archaeology, ethics, American history, social theory, and philosophy, plus linguistic perspectives on language in Christian world-views, the Bible as literature, and the prophetic work of the artist.

When the ten regional workshops are completed, a four-week national institute will convene, recruiting one-third of its faculty participation from noncoalition schools.

The coalition plans future grant proposals for similar programs in the areas of business/economics and the physical sciences, Dellenback said.