The contemporary Christian often finds Halloween an uncomfortable topic. It’s a bit like walking past a graveyard and detecting among the tombstones a thoroughly raucous party in progress—a bizarre mixture of horrible screams and merriment—and wondering who might have called it. What is this mishmash of innocent fun, ugly pranks, and witches’ taunts? And what, indeed, might be “holy” about All Hallow’s Eve?

Most of us know the holiday’s name was Christianized centuries back. But we also realize the event must have a decidedly unsavory past, what with ghouls, goblins, and ghosts decorating everything from K-Mart windows to school bulletin boards. The blending of seasonal, Christian, and pagan is remarkable.

For instance, the thoughtful believer might visit a spook house sponsored by a Christian group. Should he become entangled among the screaming and often genuinely terrified thrill seekers, he may wonder about the edifying value of butcher’s gore depicting brutalized humans, or vampires and executioners reaching out for one’s throat. At the other end of the spectrum, he hears of parents forbidding any festivities, including the use of costumes or creatures of imagination. Were he to quiz other Christians about Halloween, he’d find an awkward vagueness, or perhaps fulminations against its wickedness, or simply appreciation for pumpkins, costumes, and mystery stories.

Are there thoroughly Christian ways in which to view Halloween?

More than a thousand years ago, Christians confronted pagan rites appeasing the lord of death and evil spirits. Halloween’s unsavory beginnings preceded Christ’s birth when the druids, in what is now Britain and France, observed the end of summer with sacrifices to the gods. It was the beginning of the Celtic year, and they believed Samhain, the lord of death, sent evil spirits abroad to attack humans, who could escape only by assuming disguises and looking like evil spirits themselves. The waning of the sun and the approach of dark winter made the evil spirits rejoice and play nasty tricks. Most of our Halloween practices can be traced back to the old pagan rites and superstitions.

But the church from its earliest history has invited its people to celebrate the season differently. Chrysostom tells us that as early as the fourth century, the Eastern church celebrated a festival in honor of all saints. In the seventh and eighth centuries, Christians celebrated “All Saints’ Day” in May in the rededicated Pantheon. Eventually the All Saints’ festival was moved to November 1. Called All Hallow’s Day, it became the custom to call the evening before “All-Hallow E’en.”

Some people question the whole idea of co-opting pagan festivals and injecting them with biblical values. Did moving this celebration to November to coincide with the druidic practices of the recently conquered Scandinavians simply lay a thin Christian veneer over a pagan celebration? Have we really succeeeded in co-opting Christmas and Easter, or have neopagans taken them back with Easter bunnies and reindeer? In a sense, it’s always been the same debate: do we ignore a pagan romp, merge with it, attack it, or cover it up with seasonal fun?

History would indicate there has been much value in the church’s “Christianizing” the calendar, introducing rich traditions of celebration and spiritual disciplines. Its success could be debated, but when neighbors are fearfully sacrificing to a lord of death and dodging witches’ tricks, it would seem an apt time to celebrate the Lord of life and resurrection. The ancient Christians, after all, had thought out their strategy quite well: the idea behind All Saints’ Day is the precise opposite of chains, moaning ghosts, and evil spirits.

Yes, there are decidedly Christian ways in which we can celebrate Halloween. In our worship services and seasonal events we can interweave two great themes.

1. The lives of saints of the past. In addition to the saints depicted in Scripture, we have nearly 2,000 years of history that can and should be used as challenges to piety and faith. We Protestants have been so concerned about avoiding the veneration of saints that we often have bypassed a rich heritage of faith. Just as the Book of Hebrews gives a roll call of believers, so we can look to countless examples of equally courageous lovers of God.

2. “The life of the blessed in paradise.” Most of us have been completely unaware that All Saints’ Day is a celebration of all the saints. It is a day when Christians can remember not only those great believers of the past but also loved ones and friends who have served Christ and are now in heaven. True, it is a day to remember the lives of well-known saints and “to follow them in all virtuous and godly living.” But it is also a day to remember our own “blessed dead.”

Here is a unique opportunity for our churches. At the first news of a death, and during the first weeks of grief, the bereaved receive much attention. But how many widows ever hear their husband’s name mentioned years later by fellow Christians? Persons who were once a major part of a church’s life are forgotten—though not by their loved ones. A child who dies may be mourned by the church, but a year later that child is seldom mentioned or thought of—except by parents and siblings.

In every congregation sit people who have a great desire to speak of those in their families who loved Christ and them. Remembering such people both privately and publicly is what All Saints’ Day is about. Perhaps the pastor could give vignettes of numerous departed saints from the congregation, pointing out specific characteristics of faith worth emulating. All sorts of creative approaches could be developed. Appropriate three-minute eulogies by elders or other spiritually mature leaders intimately acquainted with the departed could be very powerful in a morning worship service. In less formal events, other approaches could be taken, including the reading of written tributes.

In Holy Days and Holidays (Edward M. Deems, ed., Gale, 1968), a compilation of sermons, literary allusions, and notes, there is a lengthy section on All Saints’ Day that includes much on the subject of Christ’s power over death and the joys of heaven. Here is one quotation from this volume:

“An eminent divine once said, ‘The first idea I had of heaven was a great city, with walls and spires, and a great many angels, but not one person I knew. Then one of my little brothers died, and then I thought of heaven as a great city, with walls and spires and one little fellow that I knew. Then a second brother died, then the third and fourth, then one of my friends died, and I began to know a little about it, but never until I let one of my own children go up into the skies had I any idea as to what heaven was like. Then the second and the third and the fourth child was taken away from me, and there came a time when I lived more with them and with God than here on the earth.’ So the best view of heaven comes to you and to me, when we have loved ones in that city of light.”

In our generation, modern medicine has made such recurring intimacy with death unusual. In past centuries, when disease and war made it much more common, celebrating All Saints’ Day was a deep comfort and inspiration. Yet even today, most of us have our own “saints” whom we long to see again. This anthology’s All Saints’ section is full of statements about death’s poignancy and parting from loved ones, but it is also full of triumphal joy, hosannas, a call for singing the songs of that far country. It is all the reverse of the dead becoming ghosts who roam cemeteries in agonized quests, or the spiritual powers taunting and torturing humans. Christ has conquered both evil and death. Our Christian response is celebration.

However, we must never be superficial about it. Evil exists. It impinges on our world. Jesus, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief, was never naïve about evil. Some, hearing the call for a celebration of light, would reassure all with a Disneyesque church production on heaven’s delights.

Unfortunately, the more gruesome aspects of Halloween observances carry a certain authenticity. After all, Dracula may not have grown batwings and sucked blood from maidens’ throats, but the historic count did impale his dinner guests. Refiner’s Fire in this magazine frequently analyzes great Christian literature, including some that depicts witches, goblins, and evil penetrations of all created matter. Our celebrations of victory in Christ are always set against the dark background of the overwhelming evil that made the Cross necessary.

Bruno Bettelheim, in The Use of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (Knopf, 1976), makes a compelling case for the value of the old fairy tales. He argues that their depictions of children’s worst fears in the form of ogres, cannibalistic stepmothers, and witches with children-sized ovens help them work out their genuine fears of death, abandonment, and unknown evils. On an even deeper level, the tales confirm to the child that evil is a reality, that the dangers are real, but that there is also a path to the good and to “salvation.”

This is true on many levels. Christians often are accused of being so quick with easy answers they seem never to have genuinely heard the questions. Until a person has wrestled over the eloquent angst of Pinter, Sartre, and O’Neill, it is doubtful that persuasive answers can be either assimilated or communicated.

And this is not necessarily an argument for sending out one’s four-year-old in a witch’s costume. Those who feel squeamish about immature children identifying with evil should not be too lightly dismissed. Nor is it necessarily healthy for witches to be depicted as darling little black-magic miscreants, as if all evil were simply a silly folklore heritage for our enlightened contemporary amusement. It is here that the Christian who has read Macdonald, Tolkien, Lewis, and Williams has an additional perspective with which to interact with children. Christians need not take a shallow “goody-two-shoes” approach, but they should develop a rich variety of ways in which to celebrate.

Let the children enjoy much lighthearted fun! Parties may include seasonal events like pumpkin-decorating contests (ever seen a Groucho Marx pumpkin head?), outrageous costumes, and lively skits, perhaps with a Linus pumpkin patch as a backdrop. There is plenty of room for unique approaches, such as one used in the Episcopal church in Fairfax, Virginia. It has celebrated an All Saints’ party for children and adults with costumes of saints from Joan of Arc and Francis of Assisi to John the Baptist. And there is a Presbyterian church in the Chicago suburbs that finished off a church-basement Halloween party with a reading of an original adaptation for Halloween of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, complete with mysterious noises and rattling chains.

We Christians can celebrate the fact that at death we pass from the land of shadows into the land of light. But this assurance is not for everyone. Halloween is also the time for thoughtful evangelism. In some Halloween settings this has been crudely done with grotesque allusions, making a burlesque of a serious message. But sensitively communicated, All Hallow’s Eve can be a ripe time for communicating Christ’s power over death and evil.

The Bible is a book full of enigma, mystery, parables, and symbols. The Christian has every right to plumb the richness of imagination and creatures of imagination. Let’s not disappoint our children with a shallow or negative response to Halloween. Let us instead celebrate one rooted in the great traditions already pioneered for us.

In his book Celebration of Discipline (Harper & Row, 1978), Richard Foster says, “Why allow Halloween to be a pagan holiday in commemoration of the powers of darkness? Fill the house or church with light; sing and celebrate the victory of Christ over darkness.”

Indeed!

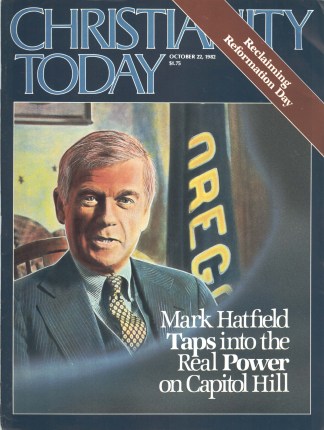

Harold L. Myra is president of Christianity Today, Incorporated. His book for children, Halloween, Is It for Real? (Thomas Nelson), was released this month.