NEWS

A controversial book published this month and a conference slated for next spring highlight the new momentum.

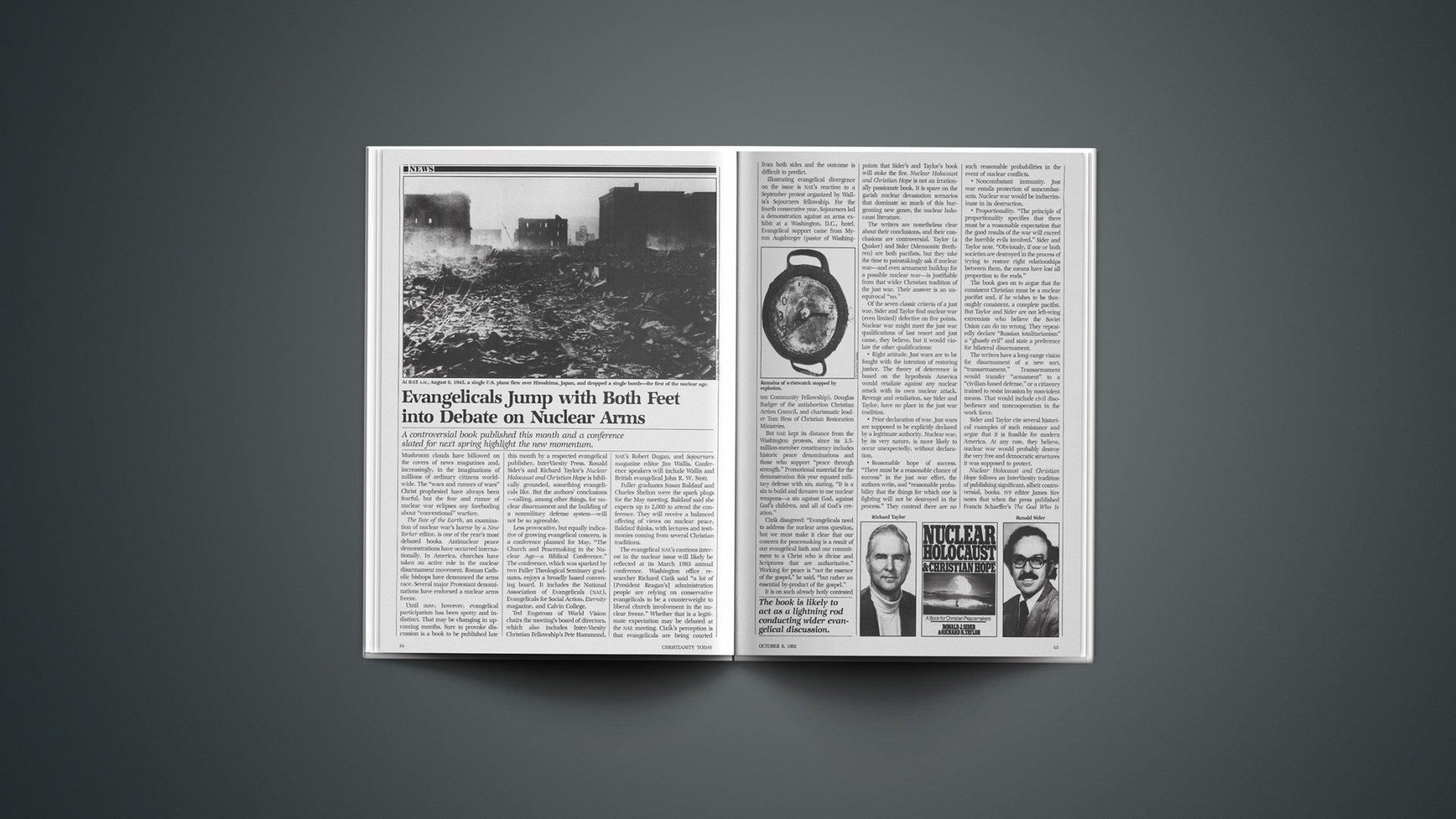

Mushroom clouds have billowed on the covers of news magazines and, increasingly, in the imaginations of millions of ordinary citizens worldwide. The “wars and rumors of wars” Christ prophesied have always been fearful, but the fear and rumor of nuclear war eclipses any foreboding about “conventional” warfare.

The Fate of the Earth, an examination of nuclear war’s horror by a New Yorker editor, is one of the year’s most debated books. Antinuclear peace demonstrations have occurred internationally. In America, churches have taken an active role in the nuclear disarmament movement. Roman Catholic bishops have denounced the arms race. Several major Protestant denominations have endorsed a nuclear arms freeze.

Until now, however, evangelical participation has been spotty and indistinct. That may be changing in upcoming months. Sure to provoke discussion is a book to be published late this month by a respected evangelical publisher, InterVarsity Press. Ronald Sider’s and Richard Taylor’s Nuclear Holocaust and Christian Hope is biblically grounded, something evangelicals like. But the authors’ conclusions—calling, among other things, for nuclear disarmament and the building of a nonmilitary defense system—will not be so agreeable.

Less provocative, but equally indicative of growing evangelical concern, is a conference planned for May, “The Church and Peacemaking in the Nuclear Age—a Biblical Conference.” The conference, which was sparked by two Fuller Theological Seminary graduates, enjoys a broadly based convening board. It includes the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), Evangelicals for Social Action, Eternity magazine, and Calvin College.

Ted Engstrom of World Vision chairs the meeting’s board of directors, which also includes Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship’s Pete Hammond, NAE’S Robert Dugan, and Sojourners magazine editor Jim Wallis. Conference speakers will include Wallis and British evangelical John R. W. Stott.

Fuller graduates Susan Baldauf and Charles Shelton were the spark plugs for the May meeting. Baldauf said she expects up to 2,000 to attend the conference. They will receive a balanced offering of views on nuclear peace, Baldauf thinks, with lectures and testimonies coming from several Christian traditions.

The evangelical NAE’S cautious interest in the nuclear issue will likely be reflected at its March 1983 annual conference. Washington office researcher Richard Cizik said “a lot of [President Reagan’s] administration people are relying on conservative evangelicals to be a counterweight to liberal church involvement in the nuclear freeze.” Whether that is a legitimate expectation may be debated at the NAE meeting. Cizik’s perception is that evangelicals are being courted from both sides and the outcome is difficult to predict.

Illustrating evangelical divergence on the issue is nae’s reaction to a September protest organized by Wallis’s Sojourners fellowship. For the fourth consecutive year, Sojourners led a demonstration against an arms exhibit at a Washington, D.C., hotel. Evangelical support came from Myron Augsburger (pastor of Washington Community Fellowship), Douglas Badger of the antiabortion Christian Action Council, and charismatic leader Tom Hess of Christian Restoration Ministries.

But NAE kept its distance from the Washington protests, since its 3.5-million-member constituency includes historic peace denominations and those who support “peace through strength.” Promotional material for the demonstration this year equated military defense with sin, stating, “It is a sin to build and threaten to use nuclear weapons—a sin against God, against God’s children, and all of God’s creation.”

Cizik disagreed: “Evangelicals need to address the nuclear arms question, but we must make it clear that our concern for peacemaking is a result of our evangelical faith and our commitment to a Christ who is divine and Scriptures that are authoritative.” Working for peace is “not the essence of the gospel,” he said, “but rather an essential by-product of the gospel.”

It is on such already hotly contested points that Sider’s and Taylor’s book will stoke the fire. Nuclear Holocaust and Christian Hope is not an irrationally passionate book. It is spare on the garish nuclear devastation scenarios that dominate so much of this burgeoning new genre, the nuclear holocaust literature.

The writers are nonetheless clear about their conclusions, and their conclusions are controversial. Taylor (a Quaker) and Sider (Mennonite Brethren) are both pacifists, but they take the time to painstakingly ask if nuclear war—and even armament buildup for a possible nuclear war—is justifiable from that wider Christian tradition of the just war. Their answer is an unequivocal “no.”

Of the seven classic criteria of a just war, Sider and Taylor find nuclear war (even limited) defective on five points. Nuclear war might meet the just war qualifications of last resort and just cause, they believe, but it would violate the other qualifications:

• Right attitude. Just wars are to be fought with the intention of restoring justice. The theory of deterrence is based on the hypothesis America would retaliate against any nuclear attack with its own nuclear attack. Revenge and retaliation, say Sider and Taylor, have no place in the just war tradition.

• Prior declaration of war. Just wars are supposed to be explicitly declared by a legitimate authority. Nuclear war, by its very nature, is more likely to occur unexpectedly, without declaration.

• Reasonable hope of success. “There must be a reasonable chance of success” in the just war effort, the authors write, and “reasonable probability that the things for which one is fighting will not be destroyed in the process.” They contend there are no such reasonable probabilities in the event of nuclear conflicts.

• Noncombatant immunity. Just war entails protection of noncombatants. Nuclear war would be indiscriminate in its destruction.

• Proportionality. “The principle of proportionality specifies that there must be a reasonable expectation that the good results of the war will exceed the horrible evils involved,” Sider and Taylor note. “Obviously, if one or both societies are destroyed in the process of trying to restore right relationships between them, the means have lost all proportion to the ends.”

The book goes on to argue that the consistent Christian must be a nuclear pacifist and, if he wishes to be thoroughly consistent, a complete pacifist. But Taylor and Sider are not left-wing extremists who believe the Soviet Union can do no wrong. They repeatedly declare “Russian totalitarianism” a “ghastly evil” and state a preference for bilateral disarmament.

The writers have a long-range vision for disarmament of a new sort, “transarmament.” Transarmament would transfer “armament” to a “civilian-based defense,” or a citizenry trained to resist invasion by nonviolent means. That would include civil disobedience and noncooperation in the work force.

Sider and Taylor cite several historical examples of such resistance and argue that it is feasible for modern America. At any rate, they believe, nuclear war would probably destroy the very free and democratic structures it was supposed to protect.

Nuclear Holocaust and Christian Hope follows an InterVarsity tradition of publishing significant, albeit controversial, books, IVP editor James Sire notes that when the press published Francis Schaeffer’s The God Who IsThere in 1968, it was seen as a work too friendly to high culture and unduly critical of the church. Yet now Schaeffer’s writing is widely esteemed and finding a new readership in staunchly fundamentalist churches. Nuclear Holocaust will bring “an awful lot of criticism now,” Sire admits, but in a few years will be considered tame.

Sider’s previous book for IVP, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger (1977) also sparked widespread debate. Just the same, it has sold about 133,000 copies and convinced most readers that Sider’s biblical commitment is indisputable.

Sire sees the publication of Nuclear Holocaust as a move “not terribly courageous. If we can’t publish books of this sort then we’re not doing our duty as a Christian publisher. It is not so much an act of courage as an act of responsibility.”

Nuclear Holocaust is unusual for IVP on some counts, however. At 372 pages, it is twice as lengthy as the average IVP title, and its pages are embellished with diagrams and photographs, which increased the publisher’s typesetting costs. Those costs were eased, Sire adds, by an agreement with the Roman Catholic Paulist Press to copublish 5,000 of the title’s 20,000 copy print-run.

Nuclear Holocaust is not the only Christian book to deal with the nuclear arms race issue. Since being published in July of 1981, Dale Aukerman’s Darkening Valley (Seabury) has sold 6,000 copies. Seabury considers sales of 1,500 to 2,000 volumes good. Two other Seabury titles on the subject have a combined sale of 8,000 copies.

Donald Kraybill’s Facing Nuclear War, just released by the Mennonite Herald Press, has gotten positive reviews, especially within the historic peace church tradition from which it comes. Nuclear Holocaust, on the other hand, seeks to appeal to an audience including but going beyond the historic peace churches. Back-cover blurbs from nonpacifist evangelicals such as John Stott, Mark Hatfield, and Vernon Grounds are part of that strategy.

Because of that, Taylor’s and Sider’s book is most likely to act as a lightning rod conducting wider evangelical discussion on a grave topic that already has much of the public talking. Sider thinks many evangelicals will listen because “they want to obey Scripture and Jesus—even when it is costly.”

BETH SPRING and RODNEY CLAPP

Urge To Merge Prevails In Three Lutheran Bodies

Meeting at their respective denominational conventions in September, three Lutheran bodies overwhelmingly approved a proposal to merge into what would be a 5.4-million-member church. The largest of the three churches, the 2.9-million-member Lutheran Church in America (LCA) voted 669 to 11 in favor of the merger.

The LCA will merge by 1987 with the 107,000-member Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches (approving 136 to 0) and the 2.35-million-member American Lutheran Church (approving 897 to 90). With present figures, the combined total of 5.4 million members would make the new Lutheran denomination (not yet named) the fifth largest religious body in the U.S. It would rank behind the Roman Catholic church, Southern Baptist Convention, United Methodist church, and National Baptist Convention, USA.

Not included in the unity proposal is the 2.6-million-member Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, which last year broke fellowship with the American Lutheran Church (ALC) for what it considered false teaching. David Preus, presiding bishop of the ALC, said that “with the help of God, I hope the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod will be drawn into this.” He noted that bringing about such a move might take a generation but “God has a way of changing things through the generations.”

Missouri Synod president Ralph Bohlmann told the LCA convention that the two denominations still lacked agreement on biblical doctrine, but rejected any suggestion that the Missouri Synod churches were “isolationist” or “ecclesiastical loners.”

The three bodies looking forward to merger also agreed to closer ties with the Episcopal church. Delegates voted to allow joint communion among Episcopalians and Lutherans.

Many Lutherans immigrated to this country from Europe in the nineteenth century. The ethnic character of American Lutheranism continued into this century. By the 1950s there were nearly two dozen Lutheran denominations, with similar doctrine, but divided by Swedish, German, Finnish, Danish, and Norwegian backgrounds.

Mergers during the 1960s created the LCA and ALC. The Association of Evanglical Lutherans was formed in 1976 when it split from the Missouri Synod.

The union of the three Lutheran bodies is expected to facilitate ecumenical moves toward other unions. Philip Potter, general secretary of the World Council of Churches, said the Lutheran merger would have a “significant impact” on the WCC.