Rights in the democratic West restrict the state. In the Soviet empire, the state is served first.

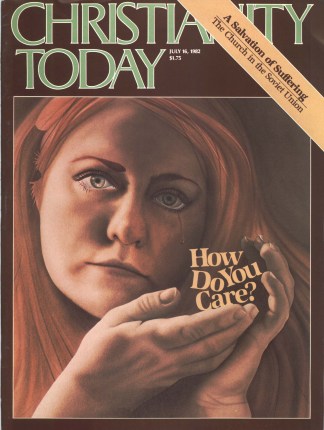

Voices are calling for help today from all directions. Some are shrill and strident, some muted and plaintive. Many come from the disinherited and the marginal, who feel shut out from the benefits of the onward movement of history. The caring Christian dare not refuse to hear and try to understand the cause and meaning of these cries for human rights and justice.

The age-old question of human rights remains a subject for study. In fact, the prestigious quarterly Ethics devotes an entire issue to it (U. of Chicago Press, Vol. 92, No. 1, Oct. 1981). The subject is filled with ambiguities, in turn reflected in a wide range of ideologies and human institutions. Many definitions clearly bypass the biblical understanding of human origins and capabilities. The issue obviously needs clarification, and many evangelicals are convinced it needs careful thought.

The Christian recognizes that both human rights and the sanctions that undergird them have their source in God as Creator and Sustainer of our universe. This view is held in opposition to much of the conventional wisdom of the day. Quite evidently there are various kinds of rights. Some are broadly defined as natural rights, and others as legal or positive rights. Both types are frequently embodied in codes set forth in various pronouncements or documents.

Document-defined natural rights are frequently called minimal rights, and define basic personal freedoms. Minimal rights are embodied in the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, its Bill of Rights, and in the several documents of the United Nations. From such minimal standards have developed extensions and elaborations.

In the western democratic tradition, such rights as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are reckoned as belonging to man as man, and do not depend upon the decrees of the state. To the Christian, such “rights” rest more fundamentally upon man as made in the image of God. Their maintenance and exercise depend upon divine providence and sovereignty. But it must be noted that Marxist states operate upon a radically different basis, which assumes that all rights rest upon legislation or upon positive law. This is why we in the West fail to understand actions within the Soviet empire.

The rights of citizens in the democratic states of the West are chiefly spelled out in terms of what the state is forbidden to do, but rights are defined in the Constitution of the Soviet Union in terms of what a citizen may do. The root difference is that, while our rights in the democratic West are restrictive of the states, rights of the citizens of the Soviet empire are granted by the state in order to foster the state.

While we would in no case identify our understanding of human rights with a typically Christian view, we believe it valid to note that when embodied in law, the Western view is more nearly in accord with Christian perspectives upon, for instance, the nature of human sinfulness and human frailty. States tend to gather power unto themselves, and one need not be a cynic to recognize that governments need restraining limits.

Enough has been said to indicate that, in our American system, rights have a basis apart from the decrees and policies of the state. But this does not offer an unambiguous basis for a typically Christian understanding of human rights, or even for a broader and more general definition of such rights. Many capable writers are addressing the continuing need for clarification of the issues.

I find the above-mentioned issue of Ethics disappointingly ambiguous at the point of the source and nature of human rights. There is little mention of rights as grounded in man’s origin in God’s creation, or of the influence of this understanding upon the quality and validity of even minimal or natural rights.

Though the articles are well written and carefully documented, the prevailing emphasis is on utility—understanding of rights as those forms of prescription that are most productive of happiness. This does not mean these chapters are without merit in calling attention to the many moral facets of rights, and to the complexity of the social exercise of rights when their employment by one as normative infringes upon the equally valid rights of others.

The authors’ use of terms like asymmetry, average view, total view, and repugnant conclusion does not conceal the lack of down-to-earth consideration of the deeper basis upon which a discussion of human rights must rest. Some of the positions expressed seem to open the way to far-fetched legal controversy, such as those set forth under “The Problem of Conception,” by Jefferson McMahan. An extreme example is suggested by lawsuits purportedly brought against parents by handicapped offspring whose physical defects allegedly could have been known before birth and led to abortion.

What is sought in these investigations and in similar attempts is a viable and believable basis for a view of human dignity that will assure a recognition of the intrinsic (as opposed to the merely conferred) quality of human rights. And though “humanistic” is today employed as a smear word, it is fair to say that most of the discussions of the question of human rights in our time proceed upon a humanistic basis that limits man to a nontranscendental quality and dimension.

While nazism and applied Marxism do represent radical examples of such views of humans, we do well to recognize implicit perils in any purely secular understanding of man. History may in the long run undergird the imperative necessity for recognition of the biblical view of humankind as God’s special creation. Even if now marred by sin, men and women assume new worth when recognized as bearing the marks of a high image and ancestry. The Incarnation and Golgotha thus bear the ultimate testimony to human worth upon which human rights rest.

Dr. Kuhn is professor of philosophy of religion, Asbury Theological Seminary, Wilmore, Kentucky.