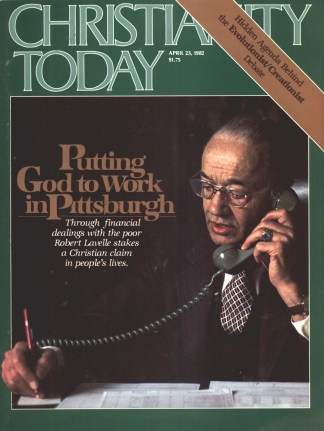

Through his financial dealings with the poor, Robert Lavelle tries to stake a Christian claim in people’s lives.

Wander through the Hill District of Pittsburgh. You will see parts of it that look like a slum: an inner-city ghetto. Burned-out and boarded-up buildings testify to businesses that have fled the area for more lucrative locations. Vacant lots reveal the vicious cycle of slum housing: the landlord who quit trying to keep it up, the tenants who gave up, the city inspector who preferred a bribe to real inspection, the drug addicts who moved in after the tenants moved out. Declared unfit for habitation, the house went down under the wrecking ball of the city’s demolition crew. You might witness a corner drug sale if you watch carefully. The numbers runner slips by.

As you continue your wandering in this area, though, you see signs of hope, of growth, and of life instead of death. You come to one of the few bright spots, an attractive building at the corner of Herron and Centre Avenues. It is Lavelle Real Estate and Dwelling House Savings and Loan.

If you are 12 years old, looking for models, you might look to the kingpin of drug sales. But you might also look to Robert R. Lavelle, the bank executive in the nice building who waves to the kids as they walk by, who sometimes finds them jobs, who visits their homes if their parents are among those who are struggling and buying a house with one of the mortgages he provides to poor black families who otherwise cannot obtain credit. The larger banks downtown would think twice before ever offering a mortgage to someone in a slum.

Officially Robert R. Lavelle is executive vice-president and secretary of Dwelling House and president of the real estate company. In practice, as a Christian applying his faith to his work, he has shaped a wide-ranging inner-city ministry, with a special emphasis on economics and housing. The key characteristic of his work is that 80 percent of his bank loans go to people who would be unable to obtain credit from other banks. “We take the person who has had problems with his credit and we try to teach him, and we give a chance to the person who normally isn’t given a chance,” he explains. He does it all in obedience and thankfulness to the One who changed his life at the age of 47.

Lavelle had done good works prior to his conversion to Christ in 1964, but his motives were different then. The son of a Church of God evangelist and a praying Christian mother, he resisted the faith of his parents until his mother’s death helped him see what he was missing in life. She was a semi-invalid after his father’s death, and would gently remind her son that though he treated her well, was a good father to his own two sons and a faithful husband to his wife Adah, he lacked one thing.

“It was the effort to attain goodness on my own strength that led me to become a Christian. I had quit doing all the things you were supposed to quit doing. I had quit smoking. I had quit drinking. I didn’t have to quit running around with other women; I always had only one wife. I guess I was one of those good Pharisees. I did good things,” he recalls, “yet I didn’t have peace, and I wasn’t happy. I couldn’t quite identify it, but it seemed like I wasn’t getting credit for the things I felt I should be getting credit for.”

Lavelle’s capacity to help exploded in the years after his conversion. His savings and loan business attracted Christian support from many who heard his testimony and placed their savings with his organization. His own vision for inner-city ministry expanded as he saw that Christ provided answers to the wide range of problems he grappled with each day as he ran two businesses in a ghetto.

Christ is the answer, he is quick to acknowledge, but that truth must be demonstrated and not merely stated, otherwise the slogan sounds simplistic to those who do not know Christ. “We need somehow to put that in the framework of everyday living and everyday existence. If Christ is the answer, his life shining through me, other people will see the good works that I do and glorify God in heaven. And the only way that Christ can get this glory is by Lavelle making sure that no one gives him credit for whatever it is that might be done that is helping someone else to have a better life. So I have to say that Christ is the answer, but he is the answer as he works through my life, as I acknowledge him as Lord, and as I make sure that others understand that it isn’t me in my strength doing this. If it were me in my strength, I would not be doing it.”

Lavelle carries out this commitment in business primarily by making his skills available to people in need, to people who would be turned away by other lending institutions because they do not have enough income or are a poor risk. Occasionally customers wonder why, and he winds up with an opportunity to share the reason for the hope that is in him.

Lavelle’s location in the heart of the Hill District ghetto is essential for his work, though he has been pressured by federal government regulators and others to move to a “better” location where there are fewer black and poor people. He stubbornly insists on staying where he is surrounded by people in need—“for educational purposes, to teach people,” he says. “Since 85 percent of learning comes from what people see, then you have to be in the community where people can see you. You can’t be in Washington, you can’t be downtown, you can’t be in one of those buildings where there are guards who keep you from getting in unless you sign your name, state your purpose. Here people can walk in.”

Much of his time is spent counseling people, explaining the responsibilities of home ownership to families with low incomes. Sometimes he winds up being an all-purpose social worker as well. “This morning I had a call from a young man who has had a life of dope, prison, problems, alcohol; a veteran,” Lavelle says, thinking of an example. “This young man was always willing to have the benefits of power without paying the price, and that got him into dope and alcohol and a lot of other things.”

He worked with the man several years, sponsoring him for parole after a prison term, providing him with a job, then helping him obtain other jobs. “He was always standing on the fence between his old life and his new life.” Lavelle helped the man buy a home for his family, counseling him when he fell behind on payments. “Each time he falters, each time he’s given a chance to make another start, it seems like there’s a strengthening quality and growth, and each time of positive action is seemingly a little longer than the last time.”

Not all the homes he finances with Dwelling House mortagages require such intense counseling. Others who fall behind on payments may receive an evening or weekend visit from Lavelle for a time of prayer and discussion. What does he say?

“I know you and I know that you have a concern for these children, that you’ve done something for them when you provided this house. We made this loan to you. You signed that you would pay on the first of each month. Now you’re providing them with a house, and that’s fine, and they do need this roof over their heads. But they need something more than that. They need a parent with integrity, who’s going to be an example of honoring his obligations, keeping his word.”

The idea is to appeal to self-respect. Lavelle seldom forecloses on home buyers who fall behind on payments, preferring to counsel and encourage. Thus his delinquency rate is higher than that of most other lending institutions. But his foreclosure rate is lower. “We only have a foreclosure when there is total abandonment,” he says. “I tell a person that if the only thing he has money for is to eat, then I’ll pay the mortgage; but I won’t let one pay for anything except food ahead of the mortgage.”

The impact of Lavelle’s ministry is difficult to measure. Home ownership has increased to 40 percent. But how do you evaluate changed lives? His example is also hard to measure. He stands in the gap, as commanded by the prophet Ezekiel: “We’re here so that these kids—you can see the buses coming now to take the kids home from school—can see a business with all the accouterments of success that they would normally equate only with a drug pusher and a numbers runner and the pimp and the prostitute and the loan shark and the alcohol dispenser and the after-hours spot. They are the only people these kids ever see with the nice car and the good living. It seems like people can’t grasp the fact that if you’re going to help people, you have to be where they are. Wherever the person who needs the help is, that is where you have to be. It’s the Jericho Road story: the man who needed help wasn’t transplanted to the church, to where the priest was going. He needed help where he was.”

For all his efforts to help poor people, though, Lavelle also has a practical, economic side to his character. “I still have to have all the technical knowledge necessary to run these businesses,” he says. “I know about the law of supply and demand, diminishing return, Gresham’s Law—you name it. I know them and I have to observe them. But I’m still saying that we must respond to needs.”

Other lending institutions have noticed this practical side and have invited Lavelle to join them, offering much higher salaries and benefits than he enjoys through Dwelling House and Lavelle Real Estate. He takes an annual salary of $7,400 from Dwelling House. His real estate company salary is $15,000 when the market is good, though he lost money in 1980. Sometimes the temptation to flee to a larger bank beckons. “It would be more comfortable, yes, with all the fringe benefits and all the back-up people and the guarantee of pension and all that. If we get a two-week vacation this year, it will be the first time we have been away for two consecutive weeks in 20 years because we can’t do it. I can’t have any excuse.”

His goal for the Hill District is 90 percent home ownership, which he thinks is the key to many of the problems of the inner city. “When we provide home ownership (equity) to poor and black people, the economics of their areas change from dope, numbers, prostitution, pimps, and loan sharks, to home ownership, good city services, police and garbage collection, quality schools, viable businesses, and jobs,” he says. “Home owners, since they pay the taxes for the school board, can demand quality schools where teachers teach instead of just keeping order. There are no troubled schools where the homes are owned. People demand the right resources.

“Home owners require business in the area. There are no businesses in black communities because there is no home ownership. Then you have jobs from businesses moving in. Kids can learn the system, earn money, and stay out of trouble. Home owners demand the government to be the government. The police protect instead of exploit. The police in this community just want their rakeoff from the dope pushers and the runners and the pimps and the prostitutes. Then you have garbage collection, regular, in a courteous manner, instead of strewn all over the place.”

He is skeptical about the ability of government to accomplish a lot on behalf of poor people, though he adds that some programs have been helpful on a short-term basis. He suggests that the government should put deposits in lending institutions that agree to counsel and help low-income families buy homes, avoiding the creation of a new bureaucracy. The urban affairs committee of the U.S. Savings League has approved the idea in the past, with some debate.

“Many people objected to the idea—the risk,” Lavelle explains. “I replied that our unwillingness to take the risk any longer is the reason government steps in and we get the laws, bureaus, programs that bloat government spending, pay large salaries, and often provide no significant return to the people.”

To reach his goal for widespread home ownership, Lavelle depends on Christians throughout the country who share his vision and keep savings accounts with Dwelling House by mail, some as small as $100. Inflation has discouraged some from joining him because he offers the normal 5½ percent interest rate. He does not try to compete with other lending institutions by offering high-yield certificates because he would not be able to keep mortgage interest rates low enough to give poor people a chance at home ownership.

But he continues to see steady, slow growth in the number of savers (approximately 3,000 now), with $7 million in assets. He is not sure why more Christians do not save with him, considering the interest in recent years among evangelicals in ministry to the inner city. “I think it’s part of the system under which we live,” he speculates. “It’s not possible for people to conceive of a profit-making institution like ours since our society sets up nonprofit organizations and government agencies to perform these services. And they just think that that is how we solve these problems, that we do not get personally involved with them.

“To see a business sharing, caring, and sacrificing so that someone else’s good will comes about without regard to what that might do to the bottom line is just not conceived of as being a practical thing. Therefore, people are able to dismiss it from their minds because they don’t see it as real. Yet they don’t inquire as to the reality of it, nor do they test it to see. It’s easier and more comfortable not to test it, but if they were to test it and see that it is true, they would have to join it or reject it, and they’re not comfortable with either of these options.”

Lavelle faces other obstacles to his goals. Robberies have pushed his insurance rates up. Savings and loans are generally facing economic difficulties, losing more deposits than they are gaining, sometimes merging or turning to the federal government for aid. The troubled list maintained by the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation keeps growing. Somehow Dwelling House continues to thrive.

“How can an institution like Dwelling House with $7 million in assets continue to survive?” he asks. “The answer, as I see it, lies in Acts 5 where Paul and James and John were being beaten in the marketplace, witnessing to Christ Jesus who was crucified and risen and ascended, and forbidden to teach and preach in his name by the Sanhedrin. They said that they must obey God rather than man. Then Gamaliel, the teacher and one of the leaders of the Sanhedrin, said not to put these people to death because, if what they were doing was of God, the Sanhedrin might find it was opposing God himself. If what they were doing was not of God, then it would fall of its own weight.

“That’s really where I feel Dwelling House Savings and Loan and Lavelle Real Estate are. If it is of God, no one will be able to prevail against us. And if what we are doing is not of God, then it will fall of its own weight—and it should, because there is no valid reason for us to exist.”

Russ Pulliam is an editorial writer and columnist for the Indianapolis News, Indiana.