Tom Key is wholly at the disposal of his many roles.

on the surface of it, a “cotton patch” rendering of the gospel might appear to be an unlikely business. After all, the gospel is surely a simple enough affair for us all to understand, and it is no harder for us to shift our imaginations over to first-century Palestine than into Oz, or Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood. We are the sort of creature who likes to be beckoned away to some other time and place. Otherwise, what is the attraction of “Once upon a time in a far off land”?

However, there is another element at work in the gospel. How shall we say it? We might attempt it thus: even though all stories are in one sense or another “the story of my life,” yet the gospel really is that story. The places (Bethlehem, Bethany, Caesarea Philippi, Golgotha, Olivet) are there in Palestine, but they are also real points in the experience of the Christian soul. The geography of the gospel is at one and the same time the geography of the heart. And this is true of the events that occur in the story: the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Epiphany, the presentation in the temple, the fasting in the desert, the Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension—they are all events in the pilgrimage of the Christian soul.

If this is true, then there is no end to the ways in which this story may be translated into local and personal situations. There is a paradox here, of course. An Eskimo or a Saxon peasant or a Bantu or a Young Life kid may be helped by having the story told in familiar pictures that touch on his own life. But on the other hand, he must also be told what a sheepfold is, or what a cross is. Those elements must always be there, one way or another. So we may say that the story is infinitely “translatable,” but also infinitely intractable. We may change the imagery for the moment; but we must also keep all the old imagery. (For modern people, for example, there might be some proximate sense in which we might speak of God as “chairperson”—heaven help us. But sooner or later he must be known as Father and King, even though those are notions alien to modern imagination.)

This is a long way of leading up to a drama review. But it is germane. Cotton Patch Gospel is now playing in New York at the Lamb’s Theatre. Starring Tom Key (well known to thousands of people for his one-man show on C. S. Lewis), and based on Clarence Jordan’s cotton-patch version of the Gospels, the show is a winner.

You tramp around rural Georgia, through Valdosta, Malone, and Two Egg en route to Atlanta (read Jerusalem), with the narrator (Saint Matthew/Tom Key) and Jesus (Tom Key also—he plays more than two dozen roles), accompanied by the four “Cotton Pickers,” a country/western/bluegrass group who play fiddle, banjo, mandolin, guitar, and bass fiddle, and act as crowds, disciples, and other extras.

If you are like this reviewer, you might think you prefer the lofty imagery of the abbey at Cluny or some such place when you indulge your reveries on Christian topics. You might tell yourself that country and western is not your scene. If you are like this, then drop everything and go to the Lamb’s Theatre in New York. You will be regaled. Your feet will be tapping and your fingers will be snapping. And then maybe even your tears will be starting, over the late Harry Chapin’s music, sung and played with irresistible ebullience by Scott Ainslie, Pete Corum, Michael Mark, and Jim Lauderdale. If you do not see the whole rural South incarnate in Pete Corum as he hunches lovingly over that bass fiddle, and if you do not love it, then something is wrong with you.

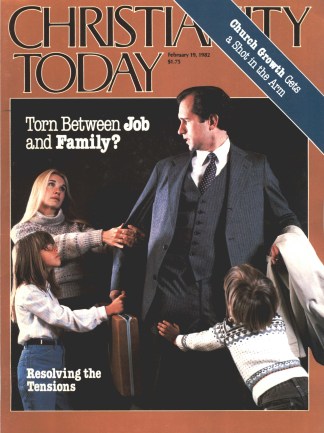

Tom Key is an actor to watch. His portrayal of C. S. Lewis was fascinating and powerful, but there were some small elements in it that seemed a bit more Key than Lewis. He seems now to be moving in the direction that all real actors must aspire to, namely to be wholly at the disposal of the role itself. It is a bravura performance. He must be at one point John the Baptist railing on the sinners, with the veins standing out in his neck; at another, Christ raising the dead girl and asking her if she’d like some breakfast; and at yet another, a cynical Georgia politician (read petty official in Jerusalem). He does it all, with vigor, suppleness, and authority.

Dr. Howard, author of numerous books, is professor of English at Gordon College, Wenham, Massachusetts.