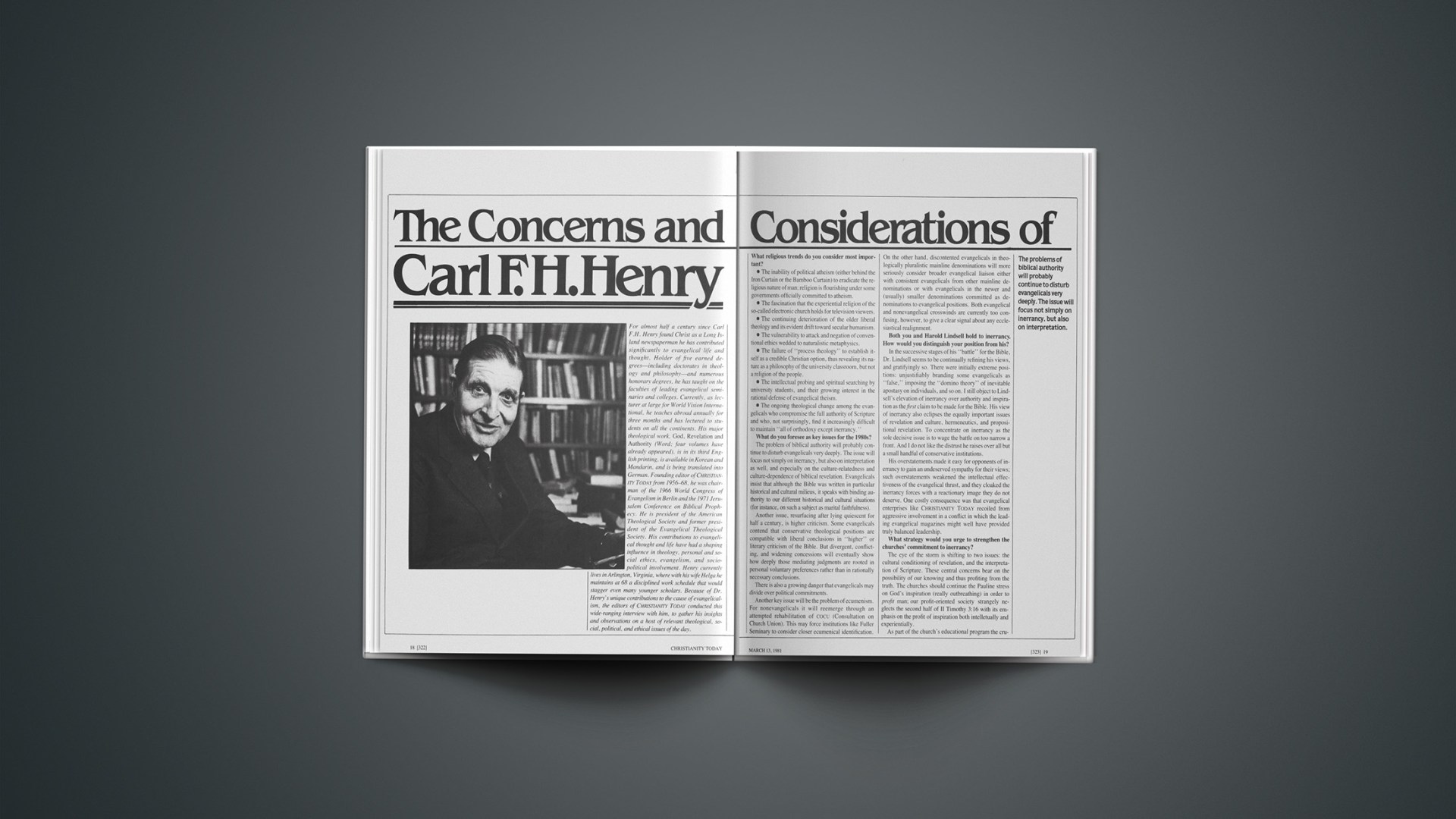

For almost half a century since Carl F.H. Henry found Christ as a Long Island newspaperman he has contributed significantly to evangelical life and thought. Holder of five earned degrees—including doctorates in theology and philosophy—and numerous honorary degrees, he has taught on the faculties of leading evangelical seminaries and colleges. Currently, as lecturer at large for World Vision International, he teaches abroad annually for three months and has lectured to students on all the continents. His major theological work, God, Revelation and Authority (Word; four volumes have already appeared), is in its third English printing, is available in Korean and Mandarin, and is being translated into German. Founding editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY from 1956–68, he was chairman of the 1966 World Congress of Evangelism in Berlin and the 1971 Jerusalem Conference on Biblical Prophecy. He is president of the American Theological Society and former president of the Evangelical Theological Society. His contributions to evangelical thought and life have had a shaping influence in theology, personal and social ethics, evangelism, and sociopolitical involvement. Henry currently lives in Arlington, Virginia, where with his wife Helga he maintains at 68 a disciplined work schedule that would stagger even many younger scholars. Because of Dr. Henry’s unique contributions to the cause of evangelicalism, the editors of CHRISTIANITY TODAY conducted this wide-ranging interview with him, to gather his insights and observations on a host of relevant theological, social, political, and ethical issues of the day.

What religious trends do you consider most important?

• The inability of political atheism (either behind the Iron Curtain or the Bamboo Curtain) to eradicate the religious nature of man; religion is flourishing under some governments officially committed to atheism.

• The fascination that the experiential religion of the so-called electronic church holds for television viewers.

• The continuing deterioration of the older liberal theology and its evident drift toward secular humanism.

• The vulnerability to attack and negation of conventional ethics wedded to naturalistic metaphysics.

• The failure of “process theology” to establish itself as a credible Christian option, thus revealing its nature as a philosophy of the university classroom, but not a religion of the people.

• The intellectual probing and spiritual searching by university students, and their growing interest in the rational defense of evangelical theism.

• The ongoing theological change among the evangelicals who compromise the full authority of Scripture and who, not surprisingly, find it increasingly difficult to maintain “all of orthodoxy except inerrancy.”

What do you foresee as key issues for the 1980s?

The problem of biblical authority will probably continue to disturb evangelicals very deeply. The issue will focus not simply on inerrancy, but also on interpretation as well, and especially on the culture-relatedness and culture-dependence of biblical revelation. Evangelicals insist that although the Bible was written in particular historical and cultural milieus, it speaks with binding authority to our different historical and cultural situations (for instance, on such a subject as marital faithfulness).

Another issue, resurfacing after lying quiescent for half a century, is higher criticism. Some evangelicals contend that conservative theological positions are compatible with liberal conclusions in “higher” or literary criticism of the Bible. But divergent, conflicting, and widening concessions will eventually show how deeply those mediating judgments are rooted in personal voluntary preferences rather than in rationally necessary conclusions.

There is also a growing danger that evangelicals may divide over political commitments.

Another key issue will be the problem of ecumenism. For nonevangelicals it will reemerge through an attempted rehabilitation of COCU (Consultation on Church Union). This may force institutions like Fuller Seminary to consider closer ecumenical identification.

On the other hand, discontented evangelicals in theologically pluralistic mainline denominations will more seriously consider broader evangelical liaison either with consistent evangelicals from other mainline denominations or with evangelicals in the newer and (usually) smaller denominations committed as denominations to evangelical positions. Both evangelical and nonevangelical crosswinds are currently too confusing, however, to give a clear signal about any ecclesiastical realignment.

Both you and Harold Lindsell hold to inerrancy. How would you distinguish your position from his?

In the successive stages of his “battle” for the Bible, Dr. Lindsell seems to be continually refining his views, and gratifyingly so. There were initially extreme positions: unjustifiably branding some evangelicals as “false,” imposing the “domino theory” of inevitable apostasy on individuals, and so on. I still object to Lindsell’s elevation of inerrancy over authority and inspiration as the first claim to be made for the Bible. His view of inerrancy also eclipses the equally important issues of revelation and culture, hermeneutics, and propositional revelation. To concentrate on inerrancy as the sole decisive issue is to wage the battle on too narrow a front. And I do not like the distrust he raises over all but a small handful of conservative institutions.

His overstatements made it easy for opponents of inerrancy to gain an undeserved sympathy for their views; such overstatements weakened the intellectual effectiveness of the evangelical thrust, and they cloaked the inerrancy forces with a reactionary image they do not deserve. One costly consequence was that evangelical enterprises like CHRISTIANITY TODAY recoiled from aggressive involvement in a conflict in which the leading evangelical magazines might well have provided truly balanced leadership.

What strategy would you urge to strengthen the churches’ commitment to inerrancy?

The eye of the storm is shifting to two issues: the cultural conditioning of revelation, and the interpretation of Scripture. These central concerns bear on the possibility of our knowing and thus profiting from the truth. The churches should continue the Pauline stress on God’s inspiration (really outbreathing) in order to profit man; our profit-oriented society strangely neglects the second half of 2 Timothy 3:16 with its emphasis on the profit of inspiration both intelletually and experientially.

As part of the church’s educational program the crucial issues in debate should be freely discussed at the various levels of intellectual competence represented in the congregations. Church libraries need monographs of solid in-depth scholarship, and literature in a more popular vein. The aims in either case should be both theoretical and practical, issuing in a scriptural world-and-life view. Our writing should help clarify the Christian’s role in society amid the vigorously presented alternatives. The goal should include a new devotion to personal and group Bible study. The Sunday school must become such an effective place to search Scripture that students change their minds and their lives.

The idea of “propositional” revelation often comes under popular attack. Some say it suggests a God who reveals himself in Euclidian terms more appropriate for classroom debate than suited to the needs of real life. What do you mean when you affirm propositional revelation?

Simply that God reveals himself in intelligently formed statements. Nobody has ever caricatured Jesus as Euclidian because he spoke divine truths in human language. For instance, after telling the parable of the woman who found her lost coin, he said, “In the same way, I tell you, there is rejoicing in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents” (Luke 15:10, NIV). The only connection between Euclid’s geometry and the biblical idea of propositional revelation that I detect is that, like every logically formed system of doctrine, Euclid’s geometry is built on axioms, or fundamental presuppositions, and that Christianity, too, has its basic “axioms” (the living God and intelligible divine revelation of truth) on which all its other claims depend. A God preoccupied with geometric abstractions is not my god; some say he was Galileo’s. Evangelical Christians do not invite the world to an unknown and unknowable X!

A proposition is simply an intelligible, logically formed statement, a declarative sentence that is either true or false. The question is: Does God tell the truth or doesn’t he? The evangelical maintains that he does. He asserts that Jesus spoke an understandable true statement when he said to the Jews, “… if you do not believe that I am the one I claim to be, you will indeed die in your sins” (John 8:24, NIV). To be sure, God reveals himself universally in nature, history, conscience, and the mind of man. But he reveals himself specially in Jesus Christ as attested by the Bible. While biblical revelation includes many commands and exhortations, it also provides at its very center true ideas about God and his relations to man and the world. We believe these biblical ideas are not just human guesses but verities that God has provided for us and the world.

The alternatives to propositional revelation are either that God gives us in the Bible only unsharable gobbledygook or that the Bible is just a book of human guesses, containing no revealed truths at all. Neoorthodoxy teaches that divine revelation is not propositional; it denies that God reveals truths about himself and his purposes. Small wonder that this God concept collapses into existential decision and finally death-of-God speculation.

Do you equate propositional revelation with the propositions or statements of the Bible?

By propositional revelation I mean not simply that the Bible is written in meaningful sentences—as most books are—but that God has revealed himself intelligibly and rationally in units of human speech involving sentences, words, and syntax that Scripture attests, and thus gives us an inspired literary document. Even when God revealed himself to the prophets in dreams and visions, the center of the revelation was always the shareable Word that the prophets prefaced by the formula: “Thus said the Lord …” God’s universal revelation in nature and history, no less than his revelation in redemptive history, is an intelligible revelation. But for man fallen into sin, the content of that general revelation is objectively stated, along with the content of God’s special saving revelation, in the truths set forth by the Bible.

In your recent debate with Professor Daane of Fuller Theological Seminary, most of us agreed that Daane in the Reformed Journal seemed to give up the case for revealed truths. But some felt that you were uneasy with revelation that is personal. Would you care to comment?

Of course revelation is personal: its source is a personal God; it is addressed to persons; special revelation is often conveyed through persons, and supremely in the person of Jesus Christ. What I criticize is his Barthian insistence on “personal nonpropositional” revelation. Neo-orthodoxy rejects any objective divine revelation of truths to chosen prophets and apostles and now objectively given in Scripture. But the God of the Bible is not a dumb mute. He not only acts in external history but also intelligibly interprets his acts. Neo-orthodox theologians emphasize divine personal internal revelation intending thereby to reinforce the reality of God. But God who cannot be known to be “there” in any objective sense, soon simply fades into nothingness, like Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire cat.

Some reviewers call you a rationalist. Is that fair to your view?

If they are pleading the cause of irrationalism they are welcome to it. Christianity is a faith—but so are Buddhism, Shamanism, communism, and humanism. The main issue for the intellectual world is whether the biblical revelation is credible; that is, are there good reasons for believing it? I am against the paradox mongers and those who emphasize only personal volition and decision. They tell us we are to believe even in the absence of good reasons for believing. Some even argue that to seek to give reasons for the faith within us is a sign of lack of trust or an exercise in self-justification. This is nonsense. Against any view that faith is merely a leap in the dark, I insist on the reasonableness of Christian faith and the “rationality” of the living, self-revealed God. I maintain that God creates and preserves the universe through the agency of the Logos, that man by creation bears the moral and rational (as opposed to irrational) image of his Maker, that despite the fall, man is still responsible for knowing God. I believe that divine revelation is rational, that the inspired biblical canon is a consistent and coherent whole, that genuine faith seeks understanding, that the Holy Spirit uses truth as a means of persuasion, that logical consistency is a test of truth, and that saving trust in Christ necessarily involves acceptance of certain revealed propositions about him. We are called to “reasonable service” (Rom. 12:1) of the Logos and, further, that nurturing “the Christian mind” is a crucial aspect of spiritual growth. Those who reject these affirmations rest their case on neo-Protestant and neo-Christian novelties rather than on historic evangelical and biblical theism.

What ethical developments are noteworthy?

First, fierce moral relativity is encompassing our secular society. Having lost its biblical moorings, our age stifles its conscience and displays an utterly shameless sensuality. One cannot but note the rampant perversion of sex, the breakdown of family life, and the cruelty and inhumanity evident in the ready massacre of fetal life. One must mention also the failure of the great universities to sustain fixed moral values, the inability of humanism to mount ethical resources requiring self-sacrifice, and the widening effort by frontier scientists to gloss over the ethical and moral implications of their experiments by an appeal to mere utilitarianism. Then too, prime-time television highlights cultural trivialities and poses little challenge to ethical waywardness. Yet I detect a new longing by disenchanted youth—after a spate of sinful living—for personal worth and for lasting love. Some are turning to the life-changing dynamic that revealed religion offers even the most profligate.

Do you see the Bible as having significance for public issues?

The Bible lays an authoritative claim upon both our generation and all nations. Neither the protests of radical biblical critics nor those of secular humanists have invalidated that claim. Neglect of the main elements of biblical revelation renders most modern intellectual centers powerless. It may seem trite, and I know it leaves unsettled the matter of political specifics, but nothing is more needed than national repentance—national repentance on the part of people ungrateful for their blessings, and unwilling to make the moral sacrifices requisite for national well-being. The times cry out for spiritual renewal alive to the high claims of divine truth and universal morality, for ethical dedication to neighborly good will, to human rights, and duties under God. A nation that settles its political specifics in this context cannot go far wrong, and even when it does, it has a built-in method of correcting its mistakes. The illusion that all the world’s problems can be solved merely by political change is disastrous. But to neglect political imperatives can likewise be naturally devastating.

How do you regard the alleged growth of the evangelical movement?

“The more, the better” makes nonsense if there is confusion about who evangelicals are. Traditional evangelical agencies seem no longer to preserve the term “evangelical” for the biblical essentials. The term is becoming a banner over many aberrations, and it increasingly means different things to different people. Some revel in “the day of the evangelical” and, to show how multitudinous the army is, boast of all possible varieties. Others define the term too narrowly and propose a purge list of “false evangelicals,” thus pitting brother against brother in the body of Christ. Still others, pleading evangelistic priorities or denominational peace, avoid or even repress open discussion of the inerrancy of Scripture.

Do you think it is possible for the NAE to become an effective counterweight to the NCC?

Given a coalescence of the right leadership, the right issues, the right program, the right strategy, and the right launch pad, NAE could still attract wide grassroots support. But many evangelicals now look upon it as almost as irrelevant as the United Nations. NAE has played too small a part in accelerating a cooperative evangelistic thrust, in coping with the evangelical authority crisis, in launching evangelicals into today’s cultural and political crisis. It has not effectively coordinated fellow evangelicals in the mainline ecumenical churches. For all that, NAE is to be commended for its many constructive activities.

How do you assess the awakening evangelical interest in politics?

Evangelicals must get their priorities straight. Christians have a biblical mandate to preach the gospel to the world and to work for national righteousness. I’m gratified that evangelicals are finding their way back into the public arena, but disconcerted lest they act unwisely and lose their opportunity. The strident criticisms by liberal intellectuals need not trouble us; evangelicals are damned for social lethargy if they are not involved, and damned for intruding sectarianism into politics if they oppose cherished prejudices. It does, I think, reflect adversely upon evangelicals when many show less interest in getting biblical truth and right into national life than in promoting a born-again candidate or in getting prayer back into the public schools. The evangelical movement needs to get publicly involved for the sake of social justice, not simply for the sake of private moral renewal.

Evangelicals tend to be single-issue or singlecandidate oriented. Their agenda is often much narrower than that of Catholics, ecumenists, and liberal Jews. However, the ecumenists, who have long championed special causes, are in no position to protest. They have criticized single-issue involvement (for example, prolife, though surely not ERA!), and have conveniently and routinely overlooked some specific moral issues, like inflation, crime, alcoholism, and addiction to cigarettes and drugs. They have baptized Communist rulers in Hanoi and Peking and Havana as revolutionary carriers of divine justice.

What should evangelicals do?

They had better agree on an agenda, make their objectives known, and move toward a better day. The American economy and foreign policy are in disarray and the moral temper of the nation is low. All citizens have public duties and are called to support the right and the good in national life. Yet the Christian fails his nation if he permits the evangelistic imperative to eclipse political duty. Evangelical churches need to speak out on both the gospel of grace and the revealed principles of social and political life.

This must be done without confusing specifics valid only for the Hebrew theocracy with civic imperatives for pluralistic nations envisioned in the New Testament. Instead of seeking political power, the churches should delineate and promote the proper use of power. God’s people should be a mighty voice for justice in the land—aware that biblical justice does not necessarily coincide with propagandistic perceptions of justice. Given a comprehensive vision and theology of politics illumined by scriptural principles, God’s people have the task of translating these into policies and platforms and support for desirable programs and candidates.

What of a Christian or evangelical party?

To take the route of a Christian party is, in my view, a mistake. But neither is it right to commit oneself unreservedly to one of the existing parties. Better yet, why not forge a moral majority in which evangelicals join forces locally with their townspeople on crucial issues? This would overcome the specter of an ecclesiastical party. Participation in local politics is good training for state and national involvement; the opportunity for political engagement in the United States is exceptional, a privilege unknown in many modern nations. The Christian ought to be politically active to the limit of his or her opportunity and competence. Unfortunately, these two qualifications do not always coincide. The Christian should try to bring into the political arena objectivity and balance, and especially, concern for the general welfare rather than personal self-interest.

What do you think of the direct role taken by prominent evangelical preachers in political campaigning?

The clergy are ordained to preach the Word of God and should “stick to their last,” that of clarifying the truth of revelation, including the Judeo-Christian principles of personal and social ethics, and of exhorting church members to exemplify and apply those principles as conscientiously and consistently as possible in public affairs.

What is your reaction to the identification of evangelicals with the new political right?

If political pluralism means anything, then evangelical Christians have as much right to promote their views as anybody else. But the Moral Majority has claimed to be not a minority but a block of 30 million votes that could decisively affect national outcomes. The secular press recognized that as an exaggeration. The Bible gives no blueprint for a universal evangelical political order. The Moral Majority was misguided by its leaders, who promoted a Christian litmus test of specific issues used to approve or disapprove particular candidates. Its spokesmen retreated to an espousal of “principles” without carefully defining them or logically deriving specifics from them.

The evangelical right differs in significant ways from the intellectual, political right. The evangelical right lacks historical perspective, theological depth, and philosophical rationale (most would be astonished to learn that classical political liberalism first promoted some positions that political conservatism now champions). It seeks a quick fix and misunderstands the historical depth of sinful perversity. Corrupt features of a society often have resulted from deeply entrenched wickedness that only a change of mind and will can alter. Effective social change requires both a political and a spiritual thrust. Shallowness accommodates a promotion of right-wing causes simply as political and economic preferences rather than on principle and by reasoned argument. Moral Majority was reluctant to dissociate itself from the campaigns of some political conservatives, including a criminally convicted (Abscam) legislator and another congressman involved in a repulsive sexual offense. In a simplistic way, moreover, the conservative litmus test leveled to the same plane of black or white, very different kinds of issues, such as abortion and the B-1 bomber. The consistent alternative to the political left, which all too often follows a pragmatic more than a principled course, is an informed and self-critical right.

Do you have any warning to evangelicals standing on the left wing of political and social involvement?

They run the risk of turning into an illusory ideology what often begins as a proper protest against a simplistic conservative solution. Socialism has failed woefully to live up to its promises, and communism even more so; the notion that they are benevolent is ill-founded. Why duplicate the errors of the ecumenical left? Pragmatically oriented programs too often end up in glaring contradictions, such as promoting American pacifism while approving the violence and revolution of others. The whole Christian heritage stands on the side of peaceful, legal, and orderly processes of change in society, rather than on the side of violence and revolution.

How influential are the mass media?

The average American gives 15 percent of his time to the mass media and less than 1 percent to the church. The emergence of the electronic church indicates that many people hunger for a personal faith. Much of this programming encourages an experiential religion, which, however, in the absence of adequate biblical teaching, can lead to theological error. The Christian movement must use the media to confront people’s basic assumptions, habits, and even subconscious drives, by sharing the truth of God’s revelation. Instead of allowing the media to crowd out the Mediator, the claim of the Mediator must be affirmed upon and through the media.

What practical steps could evangelicals take to achieve their objectives in public life?

1. In the local churches: repent and rededicate ourselves to the service of God; reject the proud pretense that evangelical politicians or even an evangelical majority can right the wrongs of the nation and perhaps of the world; clarify the relation and difference between the political and the evangelistic duty of Christians, lest misguided congregations proclaim: “Behold the candidate who solves all the problems of the nation,” and neglect the message: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.”

2. Among the leaders: share convictions, identify national goals, and explore common and divergent strategies for achieving them; links with nonevangelicals who share our political concerns and aims should also be on the agenda.

3. In the thought journals and evangelical colleges and seminaries: explore scriptural principles governing political life, of divergent inferences drawn from biblical principles; encourage articles, theses, dissertations, and books; explore and weigh national priorities; mount a great wave of public opinion in which faculty and students share; and enlist evangelical and other media in the cause of national political renewal.