The American scientists who have been trying to fathom the mystery of the Shroud of Turin since they examined it in Italy two years ago are preparing to conclude and publish their findings, possibly in April, thus closing the most sophisticated scientific investigation ever performed on an ancient object.

The team set reporting dates several times previously and failed to meet them. Some members now are pressing hard to finish, in light of the significance of what they will be able to report—or, more accurately, what they will be unable to report. “Every member of the team came aboard bound and determined to prove this was a forgery,” said John Heller, a biophysicist at the New England Institute. He and nearly all of the 30 members of the team are coming away convinced it is not a fraud.

While they have not been able to determine that the ghostly, full-length image is that of the crucified Christ, much of the evidence released so far suggests the image on the cloth is a light scorch, the product of a burst of heat and light. Thus, the final report will probably be enough to convince many that the Shroud of Turin bears the genuine imprint of Christ’s resurrection.

Ken Stevenson, an IBM computer technician and the team’s official spokesman, is already delivering slide presentations in which he concludes that the shroud is the same one used on Christ’s body. Heller doesn’t go quite that far, but he says, “It sure does make you pious.”

Samuel Pellicori, a spectroscopist at the Santa Barbara (Calif.) Research Center and a member of the team, is one who suggests a different conclusion. In the current issue of Archeology magazine, he writes that the scorch may not be a scorch at all, but simply the effect of prolonged contact with the fluids from a decaying body.

He has not been able to account, however, for the results of an astonishing experiment conducted by the leaders of the team, which seem to discount Pellicori’s hypothesis. John Jumper and Eric Jackson, two air force scientists, observed in 1974 that the intensity of the image varies in proportion to the distance a particular portion of the body would have been from the cloth. On the face, for example, the imprint of the nose and chin is stronger than the cheeks. The two scientists concluded that whatever made the image did not have to be in direct contact with the cloth, contrary to Pellicori’s view.

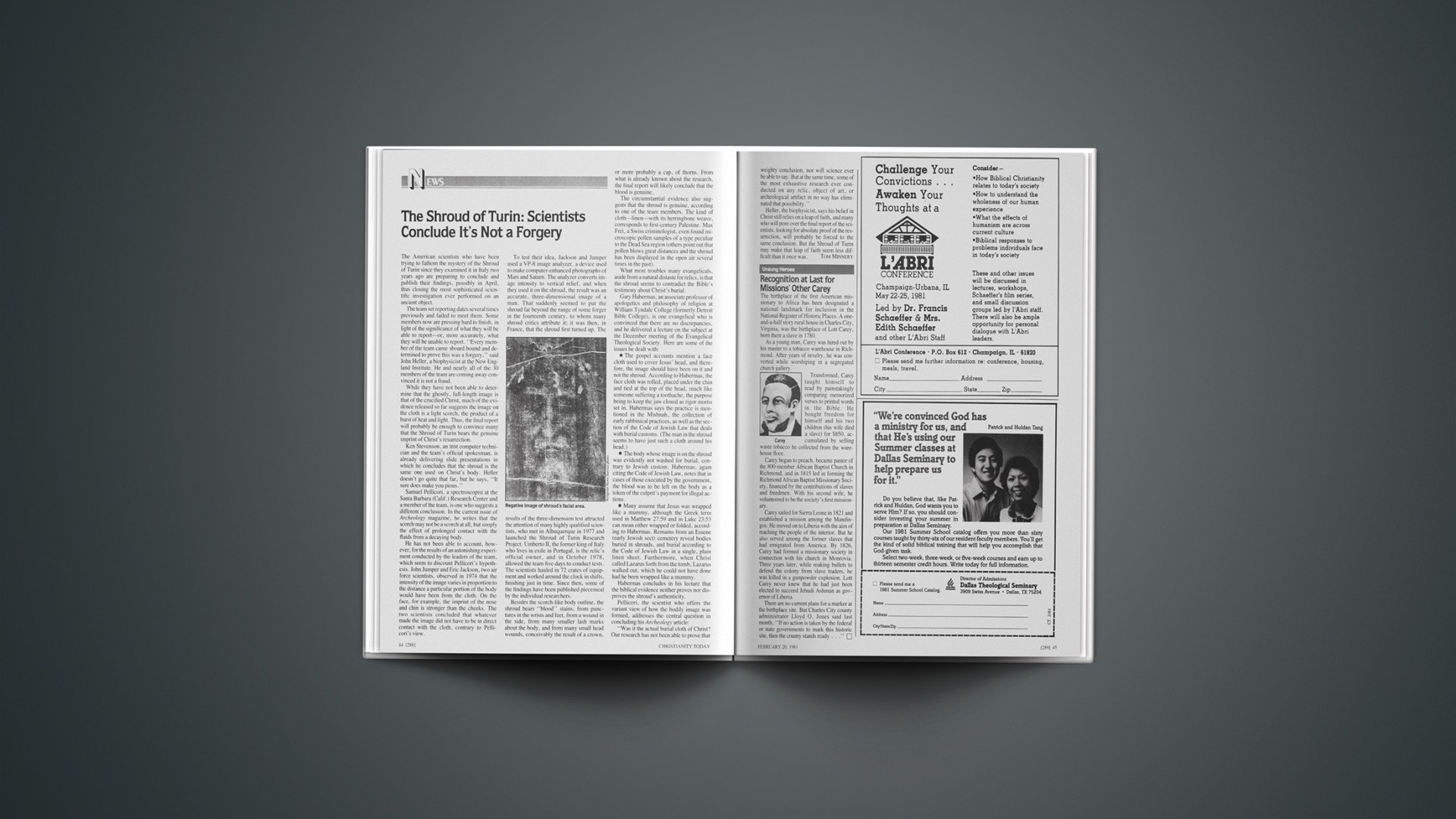

To test their idea, Jackson and Jumper used a VP-8 image analyzer, a device used to make computer-enhanced photographs of Mars and Saturn. The analyzer converts image intensity to vertical relief, and when they used it on the shroud, the result was an accurate, three-dimensional image of a man. That suddenly seemed to put the shroud far beyond the range of some forger in the fourteenth century, to whom many shroud critics attribute it; it was then, in France, that the shroud first turned up. The results of the three-dimension test attracted the attention of many highly qualified scientists, who met in Albuquerque in 1977 and launched the Shroud of Turin Research Project. Umberto II, the former king of Italy who lives in exile in Portugal, is the relic’s official owner, and in October 1978, allowed the team five days to conduct tests. The scientists hauled in 72 crates of equipment and worked around the clock in shifts, finishing just in time. Since then, some of the findings have been published piecemeal by the individual researchers.

Besides the scorch-like body outline, the shroud bears “blood” stains, from punctures in the wrists and feet, from a wound in the side, from many smaller lash marks about the body, and from many small head wounds, conceivably the result of a crown, or more probably a cap, of thorns. From what is already known about the research, the final report will likely conclude that the blood is genuine.

The circumstantial evidence also suggests that the shroud is genuine, according to one of the team members. The kind of cloth—linen—with its herringbone weave, corresponds to first-century Palestine. Max Frei, a Swiss criminologist, even found microscopic pollen samples of a type peculiar to the Dead Sea region (others point out that pollen blows great distances and the shroud has been displayed in the open air several times in the past).

What most troubles many evangelicals, aside from a natural distaste for relics, is that the shroud seems to contradict the Bible’s testimony about Christ’s burial.

Gary Habermas, an associate professor of apologetics and philosophy of religion at William Tyndale College (formerly Detroit Bible College), is one evangelical who is convinced that there are no discrepancies, and he delivered a lecture on the subject at the December meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society. Here are some of the issues he dealt with:

• The gospel accounts mention a face cloth used to cover Jesus’ head, and therefore, the image should have been on it and not the shroud. According to Habermas, the face cloth was rolled, placed under the chin and tied at the top of the head, much like someone suffering a toothache, the purpose being to keep the jaw closed as rigor mortis set in. Habermas says the practice is mentioned in the Mishnah, the collection of early rabbinical practices, as well as the section of the Code of Jewish Law that deals with burial customs. (The man in the shroud seems to have just such a cloth around his head.)

• The body whose image is on the shroud was evidently not washed for burial, contrary to Jewish custom. Habermas, again citing the Code of Jewish Law, notes that in cases of those executed by the government, the blood was to be left on the body as a token of the culprit’s payment for illegal actions.

• Many assume that Jesus was wrapped like a mummy, although the Greek term used in Matthew 27:59 and in Luke 23:53 can mean either wrapped or folded, according to Habermas. Remains from an Essene (early Jewish sect) cemetery reveal bodies buried in shrouds, and burial according to the Code of Jewish Law in a single, plain linen sheet. Furthermore, when Christ called Lazarus forth from the tomb, Lazarus walked out, which he could not have done had he been wrapped like a mummy.

Habermas concludes in his lecture that the biblical evidence neither proves nor disproves the shroud’s authenticity.

Pellicori, the scientist who offers the variant view of how the bodily image was formed, addresses the central question in concluding his Archeology article:

“Was it the actual burial cloth of Christ? Our research has not been able to prove that weighty conclusion, nor will science ever be able to say. But at the same time, some of the most exhaustive research ever conducted on any relic, object of art, or archeological artifact in no way has eliminated that possibility.”

Heller, the biophysicist, says his belief in Christ still relies on a leap of faith, and many who will pore over the final report of the scientists, looking for absolute proof of the resurrection, will probably be forced to the same conclusion. But the Shroud of Turin may make that leap of faith seem less difficult than it once was.

Unsung Heros

Recognition At Last For Missions’ Other Carey

The birthplace of the first American missionary to Africa has been designated a national landmark for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. A one-and-a-half story rural house in Charles City, Virginia, was the birthplace of Lott Carey, born there a slave in 1780.

As a young man, Carey was hired out by his master to a tobacco warehouse in Richmond. After years of revelry, he was converted while worshiping in a segregated church gallery.

Transformed, Carey taught himself to read by painstakingly comparing memorized verses to printed words in the Bible. He bought freedom for himself and his two children (his wife died a slave) for $850, accumulated by selling waste tobacco he collected from the warehouse floor.

Carey began to preach, became pastor of the 800-member African Baptist Church in Richmond, and in 1815 led in forming the Richmond African Baptist Missionary Society, financed by the contributions of slaves and freedmen. With his second wife, he volunteered to be the society’s first missionary.

Carey sailed for Sierra Leone in 1821 and established a mission among the Mandingos. He moved on to Liberia with the aim of reaching the people of the interior. But he also served among the former slaves that had emigrated from America. By 1826, Carey had formed a missionary society in connection with his church in Monrovia. Three years later, while making bullets to defend the colony from slave traders, he was killed in a gunpowder explosion. Lott Carey never knew that he had just been elected to succeed Jehudi Ashmun as governor of Liberia.

There are no current plans for a marker at the birthplace site. But Charles City county administrator Lloyd O. Jones said last month, “If no action is taken by the federal or state governments to mark this historic site, then the county stands ready …”

Malawi

Religious Freedom For All—Except Jehovah’S Witnesses

“Tell it to the commissioner of police!” the Malawian customs official barked as he proceeded to confiscate 16 pieces of literature bearing the verboten name Jehovah’s Witnesses. My wife, daughter, and I had just arrived at Chileka Airport to commence a six-month teaching assignment at the CCAP (Church of Central Africa, Presbyterian) Theological College in Zomba. The booklets were to be used for a course entitled “Christian Deviations.” This I explained to the officer—and later in a letter to the police commissioner. Weeks after the class had completed its study of Jehovah’s Witnesses, 14 Christian pamphlets on the JWs were returned; but two JW publications were retained.

Harassment of the Witnesses, who were first banned in 1967 for refusing to join the Malawi Congress Party—the nation’s sole political entity under the one-party rule of benevolent dictator H. Kamuzu Banda—crested in 1972 and again in 1975. “They are not Jehovah’s Witnesses, they are the devil’s witnesses!” Banda was quoted as saying. (The U.S.-educated physician and Church of Scotland elder forsook a lucrative medical practice in Britain and later in Ghana to lead his people to independence in 1964.) Party zealots picked up the cue and proceeded to terrorize Malawi’s 30,000 JWs. Despite strict censorship, reports of atrocities leaked out: murders, rapes, tortures, house burnings. At least two-thirds of the Witnesses fled across the border into Zambia and Mozambique, where scores reportedly died in refugee camps from drinking contaminated water. Most were repatriated, but today the sect has no visibility in the former British protectorate of Nyasaland where it had flourished since its establishment there in 1907 by Joseph Booth. No fewer than 18 Malawian religious sects are traceable to Booth, the eclectic British missionary whose theological pilgrimage from Baptist fundamentalism to Jehovah’s Witnesses via Seventh Day Baptists and Seventh-day Adventists left a trail of independent splinters in its wake.

Ironically, another Booth import, the Seventh-day Adventist church, enjoys privileged status in Malawi. On the twentieth anniversary of Martyrs’ Day (which memorializes the 57 men and 4 women slain in the struggle for freedom) in 1979, Life President Banda attended nationally broadcast services in an SDA church in Blantyre. F. E. Wilson, director of the SDA mission in Malawi, informed this reporter that Banda patronizes SDA health services and recently made unpublicized grants of 100,000 kwacha ($122,000) each to SDA dental and medical ministries.

More than half of Malawi’s 6 million people are Christians. (Malawi is the size of Pennsylvania but half as populous.) Most of the remainder—and indeed a large proportion of the Christians as well—are involved in traditional African ancestor worship and witchcraft. Muslims, who comprise 12 percent of the population, coexist peacefully with the Christian majority. The Christian sector is dominated by Roman Catholics (22.6 percent of the population) and Presbyterians (17.9 percent), followed at a distance by SDAS (1.8 percent), Anglicans (1.6 percent), and Churches of Christ (1.2 percent). Twenty-five additional churches of foreign origin include the Africa Evangelical Fellowship, the Assemblies of God, Pentecostal Holiness, Baptist, Nazarene, Greek Orthodox, and Lutheran bodies. Among approximately 40 indigenous sects are the African Gift church (which teaches that the spiritual gifts of 1 Cor. 12 are for Africans only), the Ethiopian church (which condones ancestor worship, polygamy, and beer drinking—practices forbidden by most evangelical groups), the Adam church (distinguished by worship in the nude), the Sent of the Holy Ghost, and the Church of the Holy Donkey. Baha’is and Christadelphians are small, but growing in numbers and influence.

That the Malawian fields are indeed white unto harvest is illustrated by the story of the Emmanuel Tract Fellowship. John Potter, 46, a soil conservationist from Australia, moved his family to Malawi in the summer of 1977. Although tied to his government job five-and-a-half days a week, this charismatic Methodist promptly opened an office for the distribution of tracts and Bible correspondence courses, staffed by his 70-year-old mother Audrey, and 11 largely inexperienced Malawian young people. Using volunteer colporteurs and the mails, in its first two years the ETF distributed 3,644,500 tracts, from which 112,936 decision coupons were returned, and some 204,900 Bible correspondence courses were sent to 46,700 students requesting them; 8,553 certificates were issued to those completing a series of four courses.

The ETF phenomenon bears out David Barrett’s finding that in 1978, while European and North American churches were losing 1.8 million and 950,000 members respectively, African churches added 6 million new believers (16,600 per day).

Largest of the Protestant bodies, the CCAP is markedly more conservative in faith and practice than most of its Presbyterian counterparts in the West. Discipline is strict. Expulsion is the penalty for beer drinking and unauthorized divorce. Smoking by clergy and laity is extremely rare. Due to a shortage of ordained ministers, elders take up the slack and perform preaching and pastoral duties for most CCAP congregations. (The Blantyre Synod, with more than 500 congregations, has only 45 ordained ministers.) Churches are well attended, and those who can read usually carry their Bibles as they walk, often for miles, to church. One Sunday we worshiped at the Nkhoma mission of the Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa, which merged with Scottish Presbyterian missions in 1924 to form the CCAP. When we arrived 15 minutes before the service was to begin, several hundred people had already gathered and were singing hymns lustily, and harmonizing beautifully. There was no organ or piano: such luxuries are only to be found in large city churches. A precentor, supported by a 70-voice choir, led the singing. During the service, conducted in Chichewa, the national language, 75 teen-agers were presented for church membership, climaxing two-and-a-half years of catechetical instruction. I asked the pastor, Killion Magawi, why the young people had been introduced in two groups. He explained that the first list of 22 had already been baptized, having been reared in Christian homes, but that the remaining 53 had come from pagan backgrounds and were to be baptized upon profession of faith in Jesus Christ.

Another success story is that of Riach Masomba, who began pastoral duties at the remote village of Bamba in 1961. His flock of 2,000 were divided among two churches and 30 prayer houses (satellite congregations scattered in smaller villages and rural areas). During a seven-year absence, 1966–73, Masomba pursued graduate studies in Glasgow, pastored the CCAP cathedral church in Blantyre, and served as deputy general secretary of Blantyre Synod. Then he returned to Bamba. Peddling a bicycle along the sandy roads, he would stop at intervals to organize Bible classes, many of which grew into viable congregations. Many Muslims were among his converts. In 1976 the gift of a motorcycle enabled him to extend his outreach. When he left to assume the pastorate of the Zomba congregation in 1979, membership of the Bamba parish had quadrupled to 8,000 and the number of churches and prayer houses had multiplied from 2 to 10 and from 30 to 61 respectively. Today, three pastors are required to serve the greatly enlarged parish.

Nyasaland was pioneered by David Livingstone in 1859. The first missions to survive—Livingstonia in the north and Blantyre in the south (founded in 1876)—were named after the great missionary-explorer and his birthplace in Scotland. Livingstone loved Nyasaland. Its scenic grandeur and temperate climate (in the higher elevations) reminded him of Scotland, and he envisioned a Scottish colony there in future years. How delighted he would be were he to return to Africa today and witness the dynamic spread of the gospel throughout this beautiful land!

JOSEPH M. HOPKINS

Greece

Now It’S Legal: Reading The Bible In Modern Greek

The queen was formally censured by the state church. Mobs, urged on behind the scenes by influential conservative forces, rioted for several days, chalking up a total of eight fatalities, 80 hospitalized injuries, and uncalculated property destruction. Finally, the authorities called in the police to impose order. The archbishop resigned his position. The whole cabinet resigned as well, and the government was badly shaken.

It could have happened only in Athens. The reason for the citywide insurrection 80 years ago was that Queen Olga had commissioned Alexandros Pally to translate the text of the New Testament from the original koinē into contemporary, colloquial Greek. Though Bible translations existed, they were illegal because of the Greek Orthodox church’s position that translation of the Word of God into the modern language would be “tampering with sacred text.” Still, the fact that there were no laws on the books prescribing penalties for violators was evidence that the law was not thoroughly constitutional.

Now the issue that convulsed Greece during the 1901 uprising has come to the courts again. The Court of the Magistrate, with the prosecuting attorney representing the state, issued a historic ruling implying the modern translation does not hurt the Orthodox church because it makes it possible for believers to understand the Sacred Word. (Most Greeks feel about as at home with New Testament Greek as most Americans feel with Chaucer.) The verdict states that the New Testament can be translated into modern Greek and that the resulting translation may be read in the church. The original text is still required in the liturgy.

The court verdict constitutes a turning point within the state church. It was hailed in progressive circles with evident jubilation. “The Gospel According to the Colloquial,” headlined a widely circulated daily. “Worship of God is brought nearer to man.”

The current controversy arose partly through the daring initiative of Evangelos Skordas, priest of Saint Paraskevi Church, a Greek Orthodox congregation with a strong element of young people in the Athens suburb of New Smyrna. Following the reading of the original text during the liturgy, Skordas proceeded to read a selection from the modern translation. “We took a poll of our congregation,” says Skordas, “and found that 90 percent called for reading the New Testament in modern Greek in addition to koinē. Seventy percent indicated their preference that the entire liturgy be read exclusively in modern language.”

Such a preponderance led the priest to his controversial stance in religiously conservative Greece. In a church where the only music is the male choir with the Byzantine chant, his innovations such as using an organ, forming a mixed choir, and using stringed accompaniment have also produced ire in some circles. A right-wing newspaper made a scathing attack on Skordas, which brought the matter to the attention of the prosecuting attorney for the state.

The translation Skordas read from is the common-language translation prepared for the Bible Society by Greek Orthodox scholar Vasilis Vellas and three other Orthodox university professors of theology.

Professor Spiros Agourides of the Theology School of the University of Athens affirmed, “We are not out to change the message of the New Testament. Our sole concern is to offer it to the common people in the language which they can understand. Many centuries back, the translation of the Bible into the Slavonic languages by Cyril and Methodius was made with the approval of the church. Why shouldn’t it be offered to the people in their language today?”

In recent years the dissemination of the Bible in modern language, spearheaded by the Bible Society in Athens, has gained remarkable momentum. Modern translations, though illegal, have been received with wide success. This recent decision now sanctions the use of the Bible in current translation, even authorizing its use officially in the state church.

World Scene

Evangelicals launched their own campaign in Peru late last fall—against a tide of pornography, both imported and homegrown, that is sweeping their country. A quiet and orderly antipomography demonstration, organized by the Peruvian affiliate of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, was applauded in La Prensa and other Lima newspapers. Joining the Asociación de Grupos Evangélicos Universitarios del Perú (a counterpart to InterVarsity Christian Fellowship in North America) were other Christian youth movements. However, Zeta, a locally produced pornographic magazine, chose to misinterpret their motives. It ran a two-page story claiming that the demonstration was instigated by outside pornographers out of jealousy. The title: “A Campaign Sponsored by Playboy.”

Argentina’s military government has abolished a decree that banned Jehovah’s Witnesses from the country, it was announced recently. President Jorge Rafael Videla, who is to step down next month (under guidelines set by the junta when it took power in a coup four years ago), announced the decree early in his term. That action touched off protests and charges of religious discrimination by the junta.

Appeals to West German evangelicals to work cooperatively with Pentecostal groups have so far been rebuffed. Morgan Derham, chairman of the European Evangelical Alliance, had urged acceptance of Pentecostals who adhere to the EEA basis of faith, as had chairman Manfred Otto of the German Alliance. But at a January meeting in Dollbergen, evangelical fellowships within the Hanover regional (Lutheran) church rejected formal relationships with Pentecostals. The evangelical fellowships within the established church number some 300,000 members, hold their own worship services at hours other than that of the normal church service, conduct their own Bible studies, and operate their own youth organizations. The fellowships, resentful of a second alternative to established Protestantism, have dissociated themselves from the Pentecostal movement since its beginnings early in this century.

A Council of Evangelical Christians has been formed in Yugoslavia. One hundred persons—including 50 pastors from seven denominations—met at the end of last year at Novi Sad to bring the interdenominational, cooperative grouping into being. The Protestant community makes up only about 1 percent of Yugoslavia’s 22.4 million population (the majority are Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Muslim, in that order). But in spite of that minority status, Protestants until now had shown little inclination to work together. A visit and messages by British Anglican clergyman John Stott last April prodded evangelicals to take a step toward unity. The new council represents most of the nation’s Protestant denominations. A coordinating committee was formed to establish contact with the rest.

Although the U.S. hostages have been released, other captives remain in Iran, including three Anglican missionaries from Great Britain. Arrested last August, they are Jean Waddell, 58, formerly secretary to the exiled Anglican bishop of Iran, and John Coleman, 57, and his wife, Audrey, who operated a medical clinic in Yezd.

Refugee placement has dropped off now that the plight of refugees from Southeast Asia is gone from the headlines. But the need to find homes for them has not diminished. World Relief Refugee Services has fallen behind its goal—agreed upon with the U.S. Department of State—of placing 835 refugees a month. The average for the months of last August, September, and October was only 533. T. Grady Mangham, WR vice-president for refugee services, points out that service opportunities passed up by believers will be picked up by other agencies that are not prepared to provide an evangelical witness.

The Wycliffe Bible Translators

Sil Hangs Tough Over Translator Abducted In Colombia

A leftist guerrilla movement abducted a Wycliffe Bible translator in Colombia last month, and demanded as his ransom the withdrawal from Colombia of all Summer Institute of Linguistics staff—about 100 adults plus children. SIL is the overseas counterpart of Wycliffe, and is also responsible for academic training programs in home countries.

Six men—two dressed like police—and one woman, belonging to the M-19 urban guerrilla group, forced their way into the SIL grouphouse in Bogotá at about 6:30 A.M. on Monday, January 19, looking for Alva Wheeler, the SIL director in Bogotá. Wheeler, who lives in a private residence, was not at the guest house, used to house members on errands in the capital or on their way to the villages in which they work. So the terrorists instead seized Chester Bitterman III, an American linguist who had just arrived in the city for medical treatment. They fled with him in one of the SIL vehicles.

M-19 is the same group that staged last year’s takeover of the Dominican Republic embassy in Bogotá, holding 15 ambassadors hostage for two months.

Bitterman, 28, is an economist as well as a linguist who began his work in Colombia in May 1978. His wife Brenda and two daughters. Anna and Esther, remain in Lomalinda, the SIL center in Colombia’s eastern lowlands not far from Villavicencio. Bitterman was suffering abdominal pain and had gone to Bogotá for gall bladder surgery scheduled for that Thursday. Brenda’s parents, George and Joan Gardner, are also part of SIL in Columbia. He serves as flight manager for Jungle Aviation and Radio Service, Wycliffe’s technical arm.

M-19 forwarded to several Bogotá newspapers an open letter to U.S. President Ronald Reagan, charging that SIL is linked with the U.S. Army and the CIA, and stating its intention to kill Bitterman unless SIL had completely withdrawn from Colombia by February 19. On February 2, Brenda received a handwritten letter from Chet, delivered through a newspaper, saying he was well treated, had suffered no recurrence of gall bladder attacks, and had been promised a Bible.

The SIL, which so far has had no direct contact with M-19, made no concessions to the movement’s demand and is continuing its normal program. That reaction was not improvised: it reflects a deliberate policy adopted by SIL at its regular biennial corporation conference in Mexico City in 1975. At that meeting, delegates representing the membership of SIL worldwide passed legislation in anticipation of possible threats to SIL by terrorist groups, stating that SIL would never pay ransoms or submit to terrorist demands of this kind. They reasoned that to capitulate in one instance would be to invite a rash of similar incidents around the world.

Not long after, in February of 1976, that policy was put to the test. British linguist Eunice Diments was kidnapped in the Philippines, and ransom money was demanded. None was paid, and Diments was released unharmed after 21 days.

SIL spokespersons say the institute is very firm in its intention not to capitulate to terrorist demands. “We are there by invitation of the Colombian government,” said press liaison Betty Blair, “and we intend to cooperate with the Colombian government in its resistance to the guerrillas. We are depending on the Colombian government to initiate any action. We are not taking things into our own hands. We have not contacted the U.S. state department from North America; its contacts are with Bogotá.”

Asked by a reporter who Wycliffe would turn to if the Colombian government failed to resolve the situation to its satisfaction, Bernie May, director of the Huntington Beach, California, U.S. division of Wycliffe, responded succinctly: “Nobody.”

SIL’s Latin American director, Jerry Elders, did fly to Colombia after the crisis began. And Colombian branch director Joel Stolte went up from the base of operations in Lomalinda to Bogotá to confer with the Colombian Ministry of Government.

Ties to host governments are both SIL’s strength and weakness. SIL only enters a country on the basis of a contract negotiated with its government. The contract typically calls for SIL to analyze specified minority languages, devise an alphabet for them, develop primers, dictionaries, and grammar texts, and teach the linguistic subgroup to read and write and to begin to produce its own written materials.

Officials dealing directly with SIL realize that the motive behind all SIL activity is translation of the New Testament into minority languages. Governments generally do not wish to include New Testament translation as an explicit part of SIL’s contract, but such work is approved in more general terms: SIL’s task invariably includes the translation of materials of high moral character and literary worth.

For its part, SIL calls on the host government to grant visas for its members along with certain privileges to facilitate accomplishment of the government-assigned task. Where communications with remote villages are difficult and time consuming, SIL seeks permission to establish air and radio links. When supplies and equipment must be imported for official projects, SIL seeks waivers or reductions of normal duties and taxes. Governments sometimes provide SIL with office space, and take a good deal of responsibility for the safety of SIL personnel. The result is an overseas profile distinctly different from most missionary organizations. On the surface it appears less missionary but more closely identified with the ruling regime. At first glance this would appear to make SIL less vulnerable to antimission sentiment than other groups.

But it hasn’t usually worked out that way. Those opposed to a regime in power tend to oppose SIL as well. SIL’s planes and radios feed unfounded rumors about spy connections. And anthropologists and others often criticize SIL’s Bible translation activities under state sponsorship as duplicity.

It is therefore significant that since Bitterman’s abduction the Colombian authorities have continued to speak openly about their contract relationship to SIL.

Colombia is one of about 30 countries in which SIL operates. It was incorporated in Colombia in 1942, and is now working in 36 languages out of the 53 found there. “So,” concluded a Wycliffe spokesman, “we feel like we’ve got more work there.”

Slain in Afganistan: Erik and Eeva Barendsen, 44 and 41, were found in their Kabul home on December 31 bound and stabbed to death. They had served for more then eight years at the eye hospital in Kabul with the International Assistance Mission. Erik was Dutch and his wife Finnish. The children, Asko, 5, and Ulla, 3, were in the house unharmed. No motive is known, but hostility to foreigners has increased since the Soviet occupation, and the murder occurred during the first anniversary week of that event. In spite of risk, the Barendsens had elected to remain in Afghanistan, saying, “We are the only ones to love this people.”

PER-OLOF MALK