SDA biblical scholars challenge the traditionalists.

Desmond Ford is at once a product and a catalyst of recent developments that are plunging the Seventh-day Adventist Church into a serious crisis of identity and authority.

When controversy erupted following a talk he gave in late October at a lay-sponsored forum on the campus of 2,100-student Pacific Union College in northern California, Ford—a well known SDA theologian and visiting professor from Australia—was summoned to SDA headquarters in suburban Washington, D.C., to explain his views. He had taken issue at the forum with an SDA teaching known as “the investigative judgment,” a belief that Christ entered the “sanctuary” of Daniel 8:14 (or “most holy place” of Hebrews 9) in heaven in 1844 to begin judging believers, a work that will continue until his Second Coming. The issue is important because it is a vital aspect of the church’s historical foundations. Christ did not return in 1844, as Adventist pioneers had predicted in their study of prophecy, and the investigative judgment teaching was part of the attempt to explain that in 1844 important prophecy had indeed been fulfilled.

Ford declared at the forum that Christ has been king and priest ever since his ascension and that he always knows his sheep. What happened in 1844, Ford indicated, was not a shift in heavenly geography but the raising up of a people (Adventists) who would recover the spirit of the Reformation, proclaiming “the law in its fulness and the gospel in its fulness so that all men might be judged by their response to that proclamation.” The theologian linked his dismissal of the investigative judgment to the doctrine of justification by faith, another issue troubling the church.

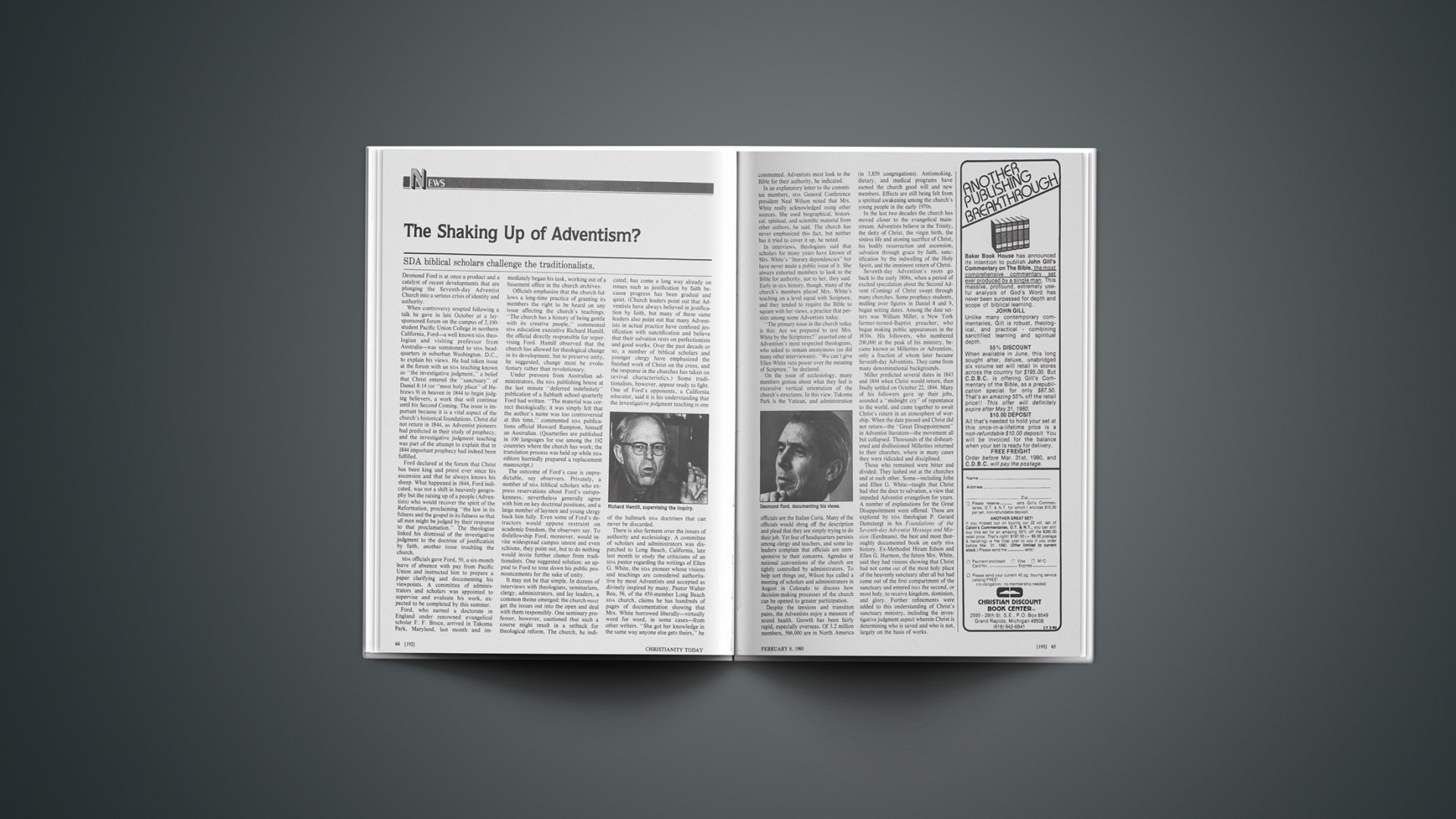

SDA officials gave Ford, 50, a six-month leave of absence with pay from Pacific Union and instructed him to prepare a paper clarifying and documenting his viewpoints. A committee of administrators and scholars was appointed to supervise and evaluate his work, expected to be completed by this summer.

Ford, who earned a doctorate in England under renowned evangelical scholar F. F. Bruce, arrived in Takoma Park, Maryland, last month and immediately began his task, working out of a basement office in the church archives.

Officials emphasize that the church follows a long-time practice of granting its members the right to be heard on any issue affecting the church’s teachings. “The church has a history of being gentle with its creative people,” commented SDA education executive Richard Hamill, the official directly responsible for supervising Ford. Hamill observed that the church has allowed for theological change in its development, but to preserve unity, he suggested, change must be evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

Under pressure from Australian administrators, the SDA publishing house at the last minute “deferred indefinitely” publication of a Sabbath school quarterly Ford had written. “The material was correct theologically; it was simply felt that the author’s name was too controversial at this time,” commented SDA publications official Howard Rampton, himself an Australian. (Quarterlies are published in 100 languages for use among the 192 countries where the church has work; the translation process was held up while SDA editors hurriedly prepared a replacement manuscript.)

The outcome of Ford’s case is unpredictable, say observers. Privately, a number of SDA biblical scholars who express reservations about Ford’s outspokenness, nevertheless generally agree with him on key doctrinal positions, and a large number of laymen and young clergy back him fully. Even some of Ford’s detractors would oppose restraint on academic freedom, the observers say. To disfellowship Ford, moreover, would invite widespread campus unrest and even schisms, they point out, but to do nothing would invite further clamor from traditionalists. One suggested solution: an appeal to Ford to tone down his public pronouncements for the sake of unity.

It may not be that simple. In dozens of interviews with theologians, seminarians, clergy, administrators, and lay leaders, a common theme emerged: the church must get the issues out into the open and deal with them responsibly. One seminary professor, however, cautioned that such a course might result in a setback for theological reform. The church, he indicated, has come a long way already on issues such as justification by faith because progress has been gradual and quiet. (Church leaders point out that Adventists have always believed in justification by faith, but many of these same leaders also point out that many Adventists in actual practice have confused justification with sanctification and believe that their salvation rests on perfectionism and good works. Over the past decade or so, a number of biblical scholars and younger clergy have emphasized the finished work of Christ on the cross, and the response in the churches has taken on revival characteristics.) Some traditionalists, however, appear ready to fight. One of Ford’s opponents, a California educator, said it is his understanding that the investigative judgment teaching is one of the hallmark SDA doctrines that can never be discarded.

There is also ferment over the issues of authority and ecclesiology. A committee of scholars and administrators was dispatched to Long Beach, California, late last month to study the criticisms of an SDA pastor regarding the writings of Ellen G. White, the SDA pioneer whose visions and teachings are considered authoritative by most Adventists and accepted as divinely inspired by many. Pastor Walter Rea, 56, of the 450-member Long Beach SDA church, claims he has hundreds of pages of documentation showing that Mrs. White borrowed liberally—virtually word for word, in some cases—from other writers. “She got her knowledge in the same way anyone else gets theirs,” he commented. Adventists must look to the Bible for their authority, he indicated.

In an explanatory letter to the committee members, SDA General Conference president Neal Wilson noted that Mrs. White really acknowledged using other sources. She used biographical, historical, spiritual, and scientific material from other authors, he said. The church has never emphasized this fact, but neither has it tried to cover it up, he noted.

In interviews, theologians said that scholars for many years have known of Mrs. White’s “literary dependencies” but have never made a public issue of it. She always exhorted members to look to the Bible for authority, not to her, they said. Early in SDA history, though, many of the church’s members placed Mrs. White’s teaching on a level equal with Scripture, and they tended to require the Bible to square with her views, a practice that persists among some Adventists today.

“The primary issue in the church today is this: Are we prepared to test Mrs. White by the Scriptures?” asserted one of Adventism’s most respected theologians, who asked to remain anonymous (as did many other interviewees). “We can’t give Ellen White veto power over the meaning of Scripture,” he declared.

On the issue of ecclesiology, many members grouse about what they feel is excessive vertical orientation of the church’s structures. In this view, Takoma Park is the Vatican, and administration officials are the Italian Curia. Many of the officials would shrug off the description and plead that they are simply trying to do their job. Yet fear of headquarters persists among clergy and teachers, and some lay leaders complain that officials are unresponsive to their concerns. Agendas at national conventions of the church are tightly controlled by administrators. To help sort things out, Wilson has called a meeting of scholars and administrators in August in Colorado to discuss how decision-making processes of the church can be opened to greater participation.

Despite the tensions and transition pains, the Adventists enjoy a measure of sound health. Growth has been fairly rapid, especially overseas. Of 3.2 million members, 566,000 are in North America (in 3,850 congregations). Antismoking, dietary, and medical programs have earned the church good will and new members. Effects are still being felt from a spiritual awakening among the church’s young people in the early 1970s.

In the last two decades the church has moved closer to the evangelical mainstream. Adventists believe in the Trinity, the deity of Christ, the virgin birth, the sinless life and atoning sacrifice of Christ, his bodily resurrection and ascension, salvation through grace by faith, sanctification by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, and the imminent return of Christ.

Seventh-day Adventism’s roots go back to the early 1800s, when a period of excited speculation about the Second Advent (Coming) of Christ swept through many churches. Some prophecy students, mulling over figures in Daniel 8 and 9, began setting dates. Among the date setters was William Miller, a New York farmer-turned-Baptist preacher, who began making public appearances in the 1830s. His followers, who numbered 200,000 at the peak of his ministry, became known as Millerites or Adventists, only a fraction of whom later became Seventh-day Adventists. They came from many denominational backgrounds.

Miller predicted several dates in 1843 and 1844 when Christ would return, then finally settled on October 22, 1844. Many of his followers gave up their jobs, sounded a “midnight cry” of repentance to the world, and came together to await Christ’s return in an atmosphere of worship. When the date passed and Christ did not return—the “Great Disappointment” in Adventist literature—the movement all but collapsed. Thousands of the disheartened and disillusioned Millerites returned to their churches, where in many cases they were ridiculed and disciplined.

Those who remained were bitter and divided. They lashed out at the churches and at each other. Some—including John and Ellen G. White—taught that Christ had shut the door to salvation, a view that impeded Adventist evangelism for years. A number of explanations for the Great Disappointment were offered. These are explored by SDA theologian P. Gerard Damsteegt in his Foundations of the Seventh-day Adventist Message and Mission (Eerdmans), the best and most thoroughly documented book on early SDA history. Ex-Methodist Hiram Edson and Ellen G. Harmon, the future Mrs. White, said they had visions showing that Christ had not come out of the most holy place of the heavenly sanctuary after all but had come out of the first compartment of the sanctuary and entered into the second, or most holy, to receive kingdom, dominion, and glory. Further refinements were added to this understanding of Christ’s sanctuary ministry, including the investigative judgment aspect wherein Christ is determining who is saved and who is not, largely on the basis of works.

Associations with Seventh Day Baptists led to the adoption of a Sabbath doctrine. Mrs. White, a prolific writer, was seen as having the “Spirit of Prophecy” by which she received revelations from God. A group of Adventists set up a headquarters in 1855 in Battle Creek, Michigan, home of vegetarian Adventist W. K. Kellogg, inventor of corn flakes. Under the leadership of Ellen White’s husband James, an editor, the SDA was formally organized in 1863. Following a spat between Kellogg and other SDA leaders, offices were moved in 1903 to Takoma Park. Mrs. White died in 1915.

The keystone doctrine of the Protestant Reformers—justification by faith (God’s declaration that a believer through faith is righteous in Christ)—apparently received little attention from the SDA pioneers. Mrs. White later stated that she and her husband had stood alone for 45 years in teaching the doctrine. Moreover, the predominant view of justification embraced by early Adventists was akin to the Catholic one hammered out at the Council of Trent: Christ died for the sins of the past, but if the believer is to survive judgment, he must provide evidence of his righteousness through obedience and good works with the aid of the Holy Spirit. This confusion of justification with sanctification, linked as it was to a pre-Advent judgment, led many Adventists into perfectionism.

The Adventists came to the brink of a theological revival in 1888, according to SDA watcher Geoffrey J. Paxton, an Anglican who is president of the Queensland Bible Institute in Brisbane, Australia. In The Shaking of Adventism (Baker, 1977), an attempt to trace the development of the doctrine of justification among Adventists, Paxton notes that two SDA ministers preached righteousness by faith at the church’s 1888 general conference in Minneapolis. Even though Mrs. White supported their views, the conference was divided. Periodic meetings have been called over the years since then to analyze what happened in 1888, and to see if some agreement could be reached on the meaning of the gospel of righteousness by faith. Desmond Ford has been a central figure at some of these meetings, pleading for the church to repent and to embrace Christ’s finished work on the cross. It is this call, amplified by Ford and others, that leads Paxton to conclude that Seventh-day Adventism is being shaken right down to its foundation.

SDA officials consider Paxton a troublemaker, and they have tried to ban him from speaking at SDA gatherings.

SDA officials are quick to emphasize that the church has always taught righteousness by faith. The full impact of the message, however, somehow seems to get bottled up.

The official SDA youth publication not long ago complained that Seventh-day Adventism’s greatest problem is related to “the consequences of years and years of unceasing perfectionism that has infiltrated every sphere of our denominational existence, be it church, Sabbath school, or home.” The result, said the paper, is “a generation of spiritually exhausted and frustrated people” who end up either pretending everything is okay or dropping out of the faith “because they know they will never reach the perfect standards of the church.”

Ford isn’t the only Australian who has gotten into trouble with traditionalists in the church over the justification issue. Robert D. Brinsmead, graduate of an SDA college in Australia and one of the most vigorous voices for theological reform among Adventists, is another. While Brinsmead was lecturing in the United States in the early 1960s, a denominational executive and a tiny Australian church disfellowshiped him from the denomination. Although he now refers to himself as an independent evangelical, he has remained in touch with Adventists around the world and is frequently called on to speak at unofficial gatherings. One of his weekend series is entitled “1844 Reexamined.” In it, he challenges the validity of virtually the entire SDA historical foundation, including the matters pertaining to the investigative judgment.

For some reason, Ford has been under heavy pressure from unnamed officials to condemn Brinsmead and his teachings publicly. Ford, however, agrees with Brinsmead on many positions and has declined to rebuke him. Says Ford about his own position: “I am not attacking any basic doctrine of the church, but I am suggesting that the traditional mode of teaching the judgment can be made more exegetically sound and more vital in its impact on the spiritual lives of our people.”

Public Events

The Exercise of Religion at the Winter Olympics

Spiritual fitness is on the program of next month’s Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. For the first time, a committee devoted solely to the spiritual needs of the athletes and spectators is part of the official Olympics organization.

“The Committee on Religious Activities of the 13th Winter Olympic Winter Games, 1980,” is the brainchild of a United Methodist pastor in Lake Placid, J. Bernard Fell. He, along with other Lake Placid clergymen, was concerned about the spiritual needs of the international contingent of athletes and spectators. In 1976, shortly after their city was designated as the winter games site, the clergymen asked the International Olympic Committee in Lausanne, Switzerland, for permission to add the committee to the official Olympics organization. The 10 clergymen members of Lake Placid’s clerical association, representing Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish faiths, are the committee’s members. They first sought an executive director, and selected Daniel J. McCormick, 33, from more than 75 applicants. McCormick, then a professor at the State University of New York in Plattsburgh, had seen an ad in his local newspaper and applied. A former Roman Catholic seminarian, he saw the job as an ideal opportunity, “covering the best of both worlds—religious programs and human services.”

Though McCormick is the only paid staff member, the committee has over 100 volunteers. It held five “consultations” in 1977 and 1978 with up to 85 representatives from over 40 church and church-related organizations. “We wanted to draw on the resources of various church groups in order to develop a comprehensive ecumenical approach, so there wouldn’t be duplication [in activities or resources of religious groups at the Olympics], but cooperation in the best possible way to address spiritual needs,” said McCormick.

Out of those meetings, the committee formulated its six main functions: providing chaplains for the athletes; arranging worship services (including a community ecumenical service on February 11, the night before the games’ official start, in the 8,000-seat Olympic arena, with Fell as main speaker); providing the news media with stories and information of religious interest; presenting religious entertainment; and arranging a “human services” center.

The amount of available money has determined the scope of committee activities. The IOC gave $100,000 to operate the 24-hour human services center in the town’s American Legion Hall. The center will have a “sobering-up service”; a lost-and-found; a center for holding and placing lost children; counseling service; a hot line; general information; and a religious literature section.

The IOC wouldn’t allow any of its funds to be used for any religious purpose, no matter how remote. Thus, between the summers of 1978 and 1979 the committee went soliciting. Originally, a $100,000 goal was set; only half that amount had been raised by last month.

“We went to the denominations, but some objected [that] it wasn’t within their means or [permitted] by commitments from their own contributors,” said McCormick. “Others didn’t want to share with ecumenical groups.” Most of the $50,000 came from the Roman Catholic Church ($30,000), the United Methodists ($10,000), the Southern Baptists ($5,000), and the Episcopalians.

The American Bible Society is providing $100,000 in the form of goods and services. It has printed flyers, identification tags, rules, and other items for the committee, as well as providing Bibles and Scripture excerpts in various languages.

The committee’s chaplaincy program is “our most important” function, said McCormick. The 15 chaplains (12 men and 3 women) represent Southern Baptist, Lutheran, United Methodist, Episcopal, and Evangelical Covenant denominations, as well as Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Jewish bodies. (A Hindu chaplain from the United Nations had to resign because of ill health.) They were chosen from 100 applicants on the basis of “linguistic, pastoral, and ecumenical experiences.”

The chaplains’ pastoral duties won’t include proselytizing: the IOC has a rule against such activities at Olympic Games sites. “We aren’t encouraging it. We’re forbidding it,” said McCormick. Any chaplain found persuading athletes “in the direction of any particular denomination [will] be asked to leave.”

The committee has come out officially against what McCormick calls “street evangelism.” That position has provoked criticism from some evangelical groups; the New York Association of Evangelicals is “perplexed and displeased,” said McCormick. The committee “is not indulging in or endorsing” evangelistic activities at the games, in order to take an “ecumenical” approach, McCormick explained.

The area’s churches will have extra services and hospitality suites. There will probably be some coffee-house-type ministries and also religious musical programs. Many groups seeking to participate will be referred to the various churches, said McCormick.

In addition, the literature racks in the human services center will be “available to interested parties who ask” for permission to put materials there, he said. “We hope to have a unified, comprehensive approach, as opposed to individual groups doing their own thing and having chaos.”

WILLIAM SHUSTER

Taxing Subjects

Deductive Reasoning

Scripture says that God loves a cheerful giver. And what makes a giver happier—and more generous—than a healthy tax deduction?

Such thinking prompted pending legislation that would allow taxpayers to deduct their charitable contributions whether or not they use the so-called standard deduction. The National Council of Churches, among other religious and nonprofit groups, has lobbied for such a bill, believing that billions of dollars in contributions are lost because of the rising standard deduction: persons find it less beneficial to itemize their deductions, and, as a result, less beneficial for them to contribute.

California businessman Parker Dale is carrying the thinking one step farther. In national newspapers, he advertises his sale of Bibles as a tax shelter.

Forbes magazine describes Dale’s method of buying Bibles wholesale, and then selling them at a profit of perhaps a dollar on each. At this rate, on a sale of 400,000 Bibles (which Dale anticipates for 1980), Dale would earn himself a tidy $400,000.

His customers, however, can donate the Bibles to churches or missions and deduct from their tax return the full retail price of the Bible, which may be three times their own cost. They may get up to $3 in deductions for every $1 they invest, with the Internal Revenue Service bearing the difference.

An archeologist digging around a millennium hence might conclude from all these Bibles that Americans were a very religious people. But Forbes reporter Howard Rudnitsky notes, “How could he understand that it wasn’t our souls we were trying to preserve but our overtaxed pocketbooks?”

Financial Irregularities

Troubling of the Waters at Bethesda Christian Center

Many people first became acquainted with Bethesda Christian Center as the progressive publisher of Virtue magazine, a slick, four-color publication for Christian women with articles showing that yes, even Christian women can have culture and wear nice clothes. Some wondered how the small, charismatic congregation of about 1,100 (500 members) could afford to publish the magazine.

But then generous tithing by members made possible a number of ventures. The center has 56 full-time employees, and operates high, middle, and grade schools, the 141-student, four-year Bethesda Christian College, a Christian arts center, a radio station, and a gas station. The church has a strong spiritual influence on the central Washington community of Wenatchee. (The church building is located in nearby Monitor.)

Pastor Larry Titus and his wife Devi, the stylish and smartly-coifed editor of Virtue magazine, started the church 11 years ago, mostly with young people coming out of the Jesus movement. A local newspaper reporter said the growing church has been controversial, but is a “solid group, a dynamic movement,” with loyal members—many of them respected persons in the community.

But now a major financial scandal threatens to curb the center’s style and mar its good name with red ink. Former business administrator James E. Eyre, 48, was being held in Chelan County Jail last month on $1 million bond, charged with first degree theft in connection with the alleged misappropriation of several million dollars in Bethesda funds.

The church released Eyre from his duties in late December after discovering “discrepancies” and “lies” in the church books, said assistant pastor Leslie Coughran. Later, Titus went to Chelan County Prosecutor E. R. Whitmore. “He [Titus] advised me of some of the things he discovered and asked me to proceed,” Whitmore told the Wenatchee World.

The affadavit filed with the charge by Whitmore specifically accuses Eyre of writing a check on a church account to pay for some electrical work at his private duplex. However, Titus told the World that several million dollars are missing.

The scandal has developed to national proportions. In a copyrighted story, the World indicated that both the Internal Revenue Service and the Federal Securities and Exchange Commission are investigating the allegations. The SEC got involved since the center, beginning in 1978, sold $850,000 in public bonds—the proceeds from which were to pay off various church debts—in Texas and other states in the South and Midwest. If, indeed, Bethesda has lost several million dollars, it could affect whether the church can repay those bonds.

The bonds were secured by a mortgage on various Bethesda properties, and sold through A. B. Culbertson, a Forth Worth, Texas firm, which specializes in public bond sales for churches, hospitals, and other nonprofit organizations.

(In many states, such as Washington and Texas, churches are exempted from filing registrations statements on public bond sales with state and federal securities officials, the World reported. The statements give full disclosure of an organization’s financial condition, and are a safeguard for potential buyers of an organization’s bonds.)

Since Eyre’s arrest, a number of church members have come forward saying he owes them money, said assistant pastor Coughran. Until recently, Coughran said, the church hadn’t known about Eyre’s private business enterprises involving church members: “The latest would seem to have been diamonds,” he said. Members have individual claims against Eyre that run as high as $255,000, and total nearly $1 million, reported Coughran.

Church officials suspect that Eyre used church money for personal investments, but say they won’t know more until a financial audit is completed. An investigation by a county special prosecutor was expected to last at least two months.

Eyre had been business administrator since 1974. Coughran said the church did not suspect wrongdoing earlier, partly because Eyre had control of all center books as administrator of a central, general accounting office. Eyre was a good friend of the Titus family. Titus told the World that Eyre had given him and his wife cars, diamond jewelry, and other expensive gifts. Titus said his wife gave Eyre the power of attorney over her financial affairs in 1977. Some members trusted Eyre enough not to request written statements of their transactions.

While Bethesda members remained loyal through the crisis, the church is concerned particularly about repaying any money owed to members, Coughran indicated. He said that 84 members made a $341,000 loan to Bethesda after Eyre requested it. That money has disappeared mysteriously, said Coughran, while the members still must be repaid.

JOHN MAUST

North American Scene

Certain American cults may in time become dominant religions, said Rodney Stark, spokesman for a team of University of Washington sociologists that just completed a study of changing religious patterns in the U.S. He said the nation’s 1,000 religious cults and sects have grown as individuals continue to leave the traditional denominations: “Cults will continue to proliferate as secularization makes ruins of the dominant churches.” The study dismissed the notion of a “Bible belt” in the South, while detecting a “cult belt” on the West coast.

The fledgling Evangelical Orthodox Church has begun official dialogue with the one-million-member Orthodox Church in America.EOC presiding bishop Peter Gillquist, an editor for Thomas Nelson Publishers, said his church is attracted to the Orthodox body’s “continuity with the historic Church and the majesty of their worship.” The Evangelical Orthodox denomination organized a year ago with 50 congregations and about 2,500 members who were previously affiliated with the New Covenant Apostolic Order, established in 1974 by Gillquist and six other former Campus Crusade for Christ staff members. The group has stated its commitment to the historic church and church authority: Gillquist announced last fall his church’s renewed emphasis on biblical teachings regarding church discipline.

The nation’s first test-tube baby project has been given the go-ahead, and doctors hope to attempt the first pregnancy next month. Virginia Health Commissioner James Kenley sanctioned an in vitro fertilization program at Norfolk General Hospital, deciding after five months of hearings and studies that the clinic would violate no state or federal laws.

A United Presbyterian pastor who has been accused of denying Christ’s deity, must be reexamined by his presbytery. The UPC Permanent Judicial Commission (highest ruling body) last month ordered that the National Capital Union Presbytery “conduct a proper examination” of Mansfield Kaseman’s doctrinal and theological beliefs. In so doing, it avoided speaking directly to protests regarding Kaseman’s alleged denial of the divinity of Christ during the presbytery’s examination. Conservatives had threatened a schism if the judicial commission upheld Kaseman’s installation. Kaseman since has said he supports Christ’s deity, but that “God is supreme.”

A popular book about angels is being questioned in charismatic circles. In response to Roland H. Buck’s Angels on Assignment (Hunter Ministries), the Melodyland School of Theology has issued five guidelines for determining whether “angelic visitations”—such as those described in the book—are authentic according to the Bible. Buck, a Boise, Idaho, pastor, has been unable to defend his book: he died suddenly of a heart attack last November.

A Baptist leader has been censured publicly by his denomination. When confronted in December by the National Association of Free Will Baptists executive committee, former executive secretary (for 12 years) Rufus Coffey confessed to committing adultery over a year’s time during his recently completed final term in office (1978–79). The committee issued a brief statement in the denomination’s magazine Contact, saying in part, “We cannot tolerate nor condone sin in any person, especially one who occupied an office of such high denominational trust.”

Personalia

In the courtroom: Former Black Panther-turned-Christian convert Eldridge Cleaver was sentenced to probation and 2,000 hours of community service work in Alameda (Calif.) Superior Court last month. Cleaver had pled guilty to three assault charges, in connection with a 1968 shootout between Black Panthers and Oakland police. Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt, another turnabout convert, became addicted to painkilling drugs after being shot and becoming paralyzed in 1978. A Franklin County, Ohio, judge ordered a delay in Flynt’s trial, involving a $160 million defamation suit filed against him by publishers of Penthouse magazine, until Flynt finishes a detoxification process.

Mission appointments: Jack Estep has been named general director of the Conservative Baptist Home Mission Society, which supports about 300 missionaries in North America. Previously the CBHMS director of church relations, Estep will succeed Rufus Jones, retiring after 28 years as the society’s first and only general director. Missionary Frank M. Severn, 39, was appointed general director of Far Eastern Gospel Crusade, succeeding Philip E. Armstrong, who becomes FEGC minister of missions.