Do you really think psychology can have any practical value for the Christian?” The man who asked this question recently is a well-known writer, teacher, and speaker. Convinced that psychology is a “godless, secular science,” he refuses to read the psychological literature, is critical of professional counseling, and staunchly maintains that the social sciences, including psychology, have nothing to offer those in the local church or parachurch organizations.

As a Christian trained in psychology, I must disagree. Just as truth about God’s created universe may come through natural sciences like medicine, or physics, or philosophical logic, or the insights of students in the humanities, so can truth come by way of psychology, psychiatry, and other social sciences. There is, of course, much within psychology that the Christian cannot accept. Some psychological conclusions about man’s nature, for example, some techniques used by professional counselors, and some proposals for altering our future are clearly contrary to Christian ethics and the teaching of Scripture. If we test our psychological conclusions empirically, logically, and against the inspired Word of God, however, we will discover that the psychological sciences contain much of practical value to the Christian seeking to serve Christ both inside and outside the church.

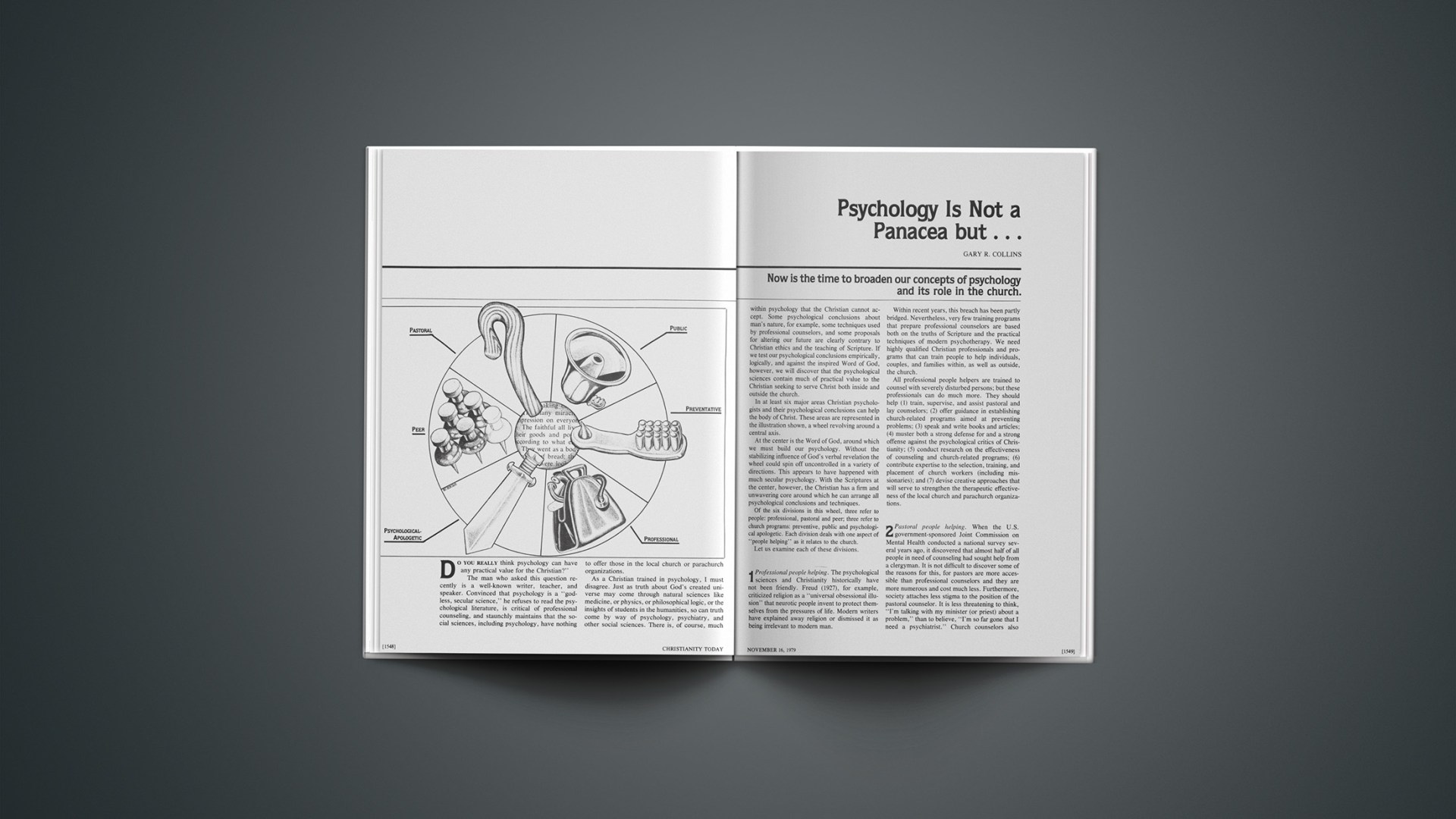

In at least six major areas Christian psychologists and their psychological conclusions can help the body of Christ. These areas are represented in the illustration shown, a wheel revolving around a central axis.

At the center is the Word of God, around which we must build our psychology. Without the stabilizing influence of God’s verbal revelation the wheel could spin off uncontrolled in a variety of directions. This appears to have happened with much secular psychology. With the Scriptures at the center, however, the Christian has a firm and unwavering core around which he can arrange all psychological conclusions and techniques.

Of the six divisions in this wheel, three refer to people: professional, pastoral and peer; three refer to church programs: preventive, public and psychological apologetic. Each division deals with one aspect of “people helping” as it relates to the church.

Let us examine each of these divisions.

1Professional people helping. The psychological sciences and Christianity historically have not been friendly. Freud (1927), for example, criticized religion as a “universal obsessional illusion” that neurotic people invent to protect themselves from the pressures of life. Modern writers have explained away religion or dismissed it as being irrelevant to modern man.

Within recent years, this breach has been partly bridged. Nevertheless, very few training programs that prepare professional counselors are based both on the truths of Scripture and the practical techniques of modern psychotherapy. We need highly qualified Christian professionals and programs that can train people to help individuals, couples, and families within, as well as outside, the church.

All professional people helpers are trained to counsel with severely disturbed persons; but these professionals can do much more. They should help (1) train, supervise, and assist pastoral and lay counselors; (2) offer guidance in establishing church-related programs aimed at preventing problems; (3) speak and write books and articles; (4) muster both a strong defense for and a strong offense against the psychological critics of Christianity; (5) conduct research on the effectiveness of counseling and church-related programs; (6) contribute expertise to the selection, training, and placement of church workers (including missionaries); and (7) devise creative approaches that will serve to strengthen the therapeutic effectiveness of the local church and parachurch organizations.

2Pastoral people helping. When the U.S. government-sponsored Joint Commission on Mental Health conducted a national survey several years ago, it discovered that almost half of all people in need of counseling had sought help from a clergyman. It is not difficult to discover some of the reasons for this, for pastors are more accessible than professional counselors and they are more numerous and cost much less. Furthermore, society attaches less stigma to the position of the pastoral counselor. It is less threatening to think, “I’m talking with my minister (or priest) about a problem,” than to believe, “I’m so far gone that I need a psychiatrist.” Church counselors also bring the healing balm of religion to their guidance, and because they are familiar figures they are often more trusted by people in need than professionals who may be perceived as aloof “mind readers.”

In addition to its research, the Joint Commission revealed some startling conclusions about help from pastoral people. “Pastoral counseling by clergymen is unquestionably the single most important activity of the churches in the mental health field.” And, Jahoda says, “A host of persons untrained or partially trained in mental health principles and practices—clergymen … and others—are already trying to help and treat the mentally ill in the absence of professional resources.… With a moderate amount of training through short courses and consultation on the job, such persons can be fully equipped with an additional skill as mental health counselors.… Teaching aid must be provided … schools of theology … and others so that they may have part-time and full-time faculty members who will integrate mental health information into the training programs of these professionals.”

Since this pronouncement, seminaries and other religious training institutions have invested considerable time and money in programs designed to train pastors and potential pastors as people helpers. In one sense, the training has just begun; in the future it needs to be more in-depth, more practical, and more a part of seminary curricula. In another sense, however, many pastors are already performing in this role at full capacity, whether or not they have been trained in counseling. It is common to find pastors who are swamped with counselees, overwhelmed by the needs of those all around them, frustrated by a lack of time to get their noncounseling work done, and discouraged by the inability to find professionals to whom they can refer needy people. Lay people within the church must be trained as people helpers, and encouraged to bear each other’s burdens, to rejoice with those who rejoice, and to weep with those who weep (Gal. 6:2; Rom. 12:15).

3Peer people helping. If you had a personal problem, who is the first person to whom you would turn for help? For many people, the answer appears to be, “I would turn to a friend, or a neighbor, or a relative,” for these are the people who understand us best and who are most readily available in times of need. They comprise what is perhaps the most influential people-helping force in the country.

Friends and relatives of needy people can be effective as people helpers. When Robert Carkhuff surveyed the literature on peer or “paraprofessional” helpers, he concluded that lay persons, with or without training, could counsel as well as—and in some cases better than—professional counselors. This was true whether these peer counselors were working with normal adults who were having problems, with children, with psychiatric patients in out-patient clinics, or with psychotics in psychiatric hospitals. Unconcerned about professionalism, more relaxed, informal, down-to-earth, and compassionate, these lay counselors have demonstrated in numerous studies that they can be highly competent people helpers.

Within recent years, several programs have appeared for the training of peer counselors; however, little has been developed to aid in the specific task of training laymen within the church. Initial research with one of these programs (Collins, How to Be a People Helper, 1976), has demonstrated that Christian peer counselors can raise their levels of empathy, warmth, and genuineness, and increase their counseling skills as the result of a relatively brief training program. The further training of lay persons needs to take place within the local church and church-related organizations. Such training must focus on such areas as teaching of counseling skills and techniques, development of counselor attributes, methods of crisis intervention, identification of potential and developing problems in oneself and others, the importance and techniques of referral, evaluation of self-help formulas or books, ways to build greater family unity and stability, and some understanding of the dynamics and treatment of depression, anxiety reactions, self-esteem problems, and other common adjustment difficulties.

4Psychological-apologetic people helping. Several decades ago, when the controversy over evolution was a frequent topic of discussion among Christians, biology was viewed as the greatest intellectual threat to the church. More recently, however, it appears that psychology has been cast in this role.

A Christian student in a university classroom often hears convincing arguments designed to prove that conversion is primarily an emotional reaction to techniques of persuasion, that prayer is wishful thinking, that miracles are impossibly nonscientific, that worship is a ritual and thus evidence of compulsive and obsessive neuroses, that God is a projection of an illusory father figure, or that all religion is a result of conditioning. A student can easily be persuaded to abandon the faith in favor of the religious conclusions of psychological science if he or she has not been prepared to counteract this teaching.

Christian apologetics can answer most psychological arguments decisively, but freshmen students in psychology classes do not often realize this, and neither do many of their professors. As psychology becomes more technical and sophisticated, so can the arguments against religion, especially Christianity. Knowledgeable, committed scholars who can think clearly and are thoroughly acquainted with the methods and conclusions of modern psychology must decisively counteract these challenges to the Christian faith.

5Public people helping. It is easy to misinterpret books or articles or speeches about human needs. Needy people especially tend to hear or see only what they are looking for, and sometimes pull information out of context in an attempt to find help with a problem.

Thousands of people apparently look to the communications media for help; and many of them evidently find solace and guidance through reading or listening to tapes and sermons and “how to” lectures. Professional psychologists are inclined to criticize people helping in public, particularly if naive persons are led to believe that one specific book or self-help formula will solve all their problems. Human difficulties are rarely so easily overcome, and when a formula is tried and found not to work, the user often feels guilty for failing, especially if the formula he tried was tied to the Bible and presented as “the scriptural answer” to his problems.

However, this is the only help some people will ever get. It is threatening and uncomfortable for them to talk about their problems, even to their friends; as a result, many people turn to books, tapes, or lectures and hope that these will provide help, but anonymously. And help is indeed provided! Public people helping, however, could be better—these guides should be clearer, offer more realistic promises, be more biblically based, more alert to the established findings of modern psychology, and less dependent for support on single case histories and poor biblical exegesis. To be effective, public people helping should adhere to clearly established principles of homiletics and communication. It should also stress individual differences so people will feel less guilty when principles or suggestions fail to work in their own lives. The value and respectability of discussing problems with a friend, pastor, or professional counselor should be emphasized as preferable to seeking all help from the impersonal pages of a book or the generalized words of a sermon or lecture.

6Preventive people helping. Prevention is always the best way to counteract disease. In medicine, vaccination programs, health education, and community projects for disease control are familiar ways to avoid or contain illness.

In 1964, Gerald Caplan’s Principles of Preventive Psychiatry called for a program to prevent psychological problems. Caplan described three aspects of prevention: avoid problems before they emerge, check developing problems before they worsen, and eliminate harmful effects from previous problems.

People must be aided in identifying and avoiding potential stresses. (Premarital counseling is an example of this.) People should be helped in anticipating and preparing for such future crises as retirement, divorce, or death. Lay people should be taught to recognize developing problems in others so that they can offer help before problems grow worse. We must learn to use worship, study programs, discussion groups, church socials, and other activities—whether or not they are religious—to help people avoid problems or show them how to cope more effectively with them. The church is strategic for the prevention of psychological problems. It is in contact with whole families over extended periods of time. Church leaders can visit in homes and are present in times of crisis and at life’s turning points. Sunday school teachers, youth leaders, elders, deacons, and other laymen within the body of Christ working closely with fellow Christians are able to intervene in a helpful, nonthreatening way before serious problems develop.

In conclusion, these six areas clearly relate to the ministry of the local church. But the influence of professional, pastoral, peer, psychological-apologetic, public, and preventive psychology is not limited to the local body of believers. Missions, seminaries, Christian colleges, youth programs, denominations, evangelistic associations, and radio and television outreaches all could benefit from such a biblically based psychology.

In past years we have trained a few Christian professionals and focused attention on training pastors to counsel with parishioners in times of crisis. Now is the time to broaden our concept of psychology and its role in the church of Jesus Christ. Psychology is not a panacea. But this science of human behavior does have practical value that is far greater than many Christians have recognized. There is a challenge now before Christian professionals and nonpsychologists to work together to build a biblically based psychology that can have a broader influence on the lives of Christians, on local churches, and on parachurch organizations.

G. Douglas Young is founder and president of the Institute of Holy Land Studies in Jerusalem. He has lived there since 1963.