If you read the critics, you might not suspect that J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, the first true epic to come along since Milton revitalized Homer’s and Virgil’s genre, was a monumental work. That its followers, as with Abraham’s seed, are as numerous as the sands. That there are people who meet each week to play Middle-earth games. That maps, calendars, pictures, puzzles, and deluxe editions of the trilogy sell in the millions year after year. I suspect that the critics and the audiences of Ralph Bakshi’s animated version of The Lord of the Rings, released by United Artists, will be just as far apart.

With few exceptions, the critics find it a bad film. The audiences don’t. Walt Disney, Stanley Kubrick, and John Boorman each thought at one time or another about putting The Lord of the Rings on film. Bakshi, the director, hasn’t created a flawless film; here is no Star Wars; neither is it Billy Jack. But considering the sprawl and scope of Tolkien’s story, Bakshi in a somewhat long 131 minutes captures well the atmosphere of an earlier and easier time.

The most compelling aspect of the film comes at the beginning with the recitation of the ring poem and the explanation of how the ring came to Frodo. Black silhouettes against a blood-red background set the tone and put the plot in motion. Those critics who found the film difficult to follow have watched too much television. They could do with a course in Shakespeare, whose popular plots are notoriously complex.

On to the shire. The film moves rapidly, streamlining the birthday party, the story of Gandalf’s search for the truth of the ring, and Frodo’s trip to Rivendell. Tom Bombadil and the Barrow-wights don’t appear. The stay at Rivendell, too, is shortened, as is the first leg of the journey up to the separation of the company.

Some straight lines were necessary. The beginning is as good a place as any to remove Tolkien’s curves, though I wish the battle of Weathertop hadn’t been so underplayed. Bakshi opted for the more subtle aspects of book one and he gave more time to the later battle scenes. But since he already had an unusually long film, why add a scene that doesn’t occur in Tolkien: Saruman giving his orcs a pep talk before the big battle.

Several animation techniques seem distracting at first. The director, to achieve as much realism as he could, staged the action live, and produced his animation from that. No cartoon character has ever used so many facial expressions or talked with so mobile a mouth as does a Bakshi hobbit. Once you get over the surprise, the technique aids your belief that these are real characters. That also goes for the animals. His horses must have been a labor of love. Galloping, eating, sniffing—they move as realistically as any horse John Wayne ever rode.

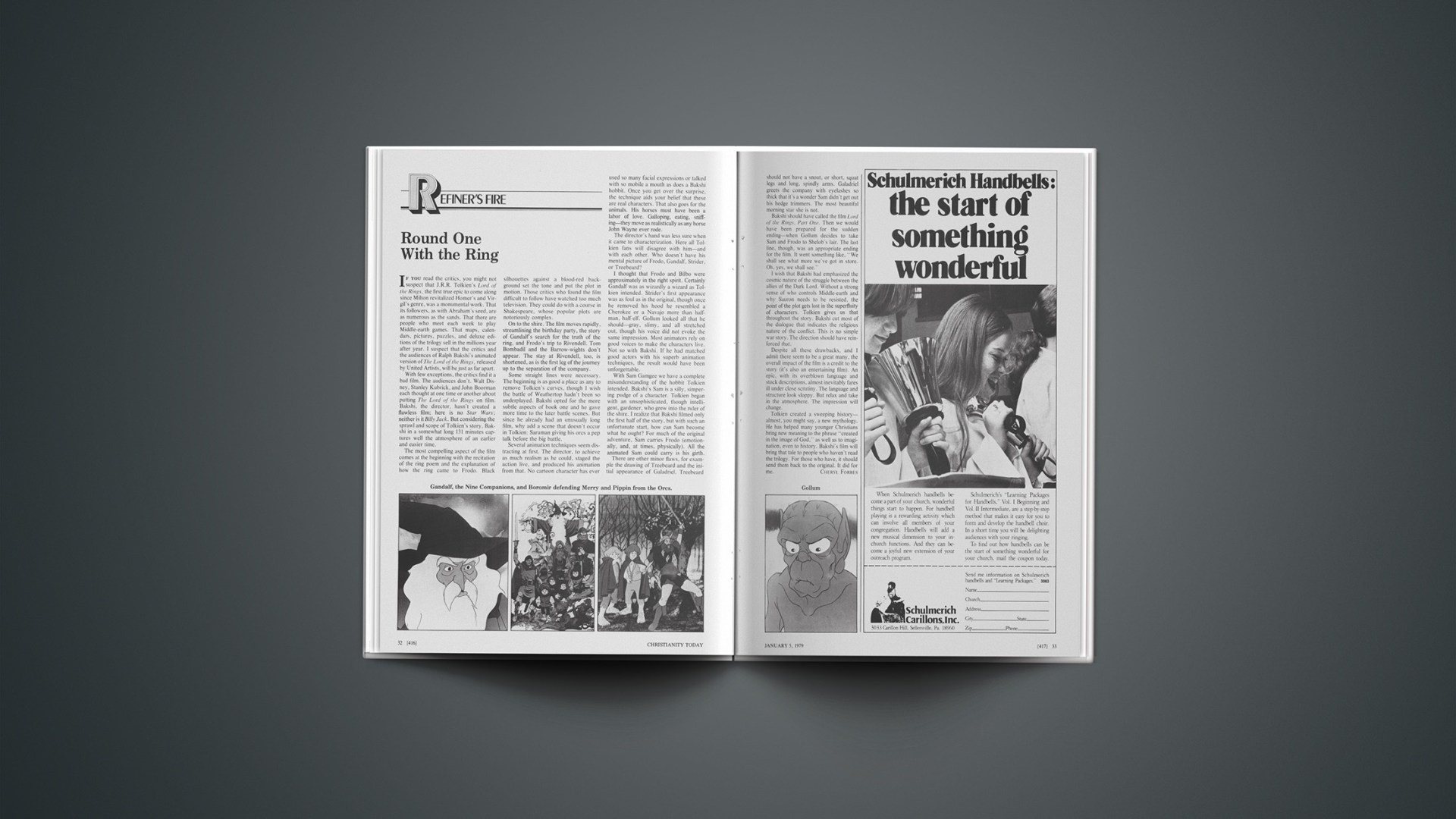

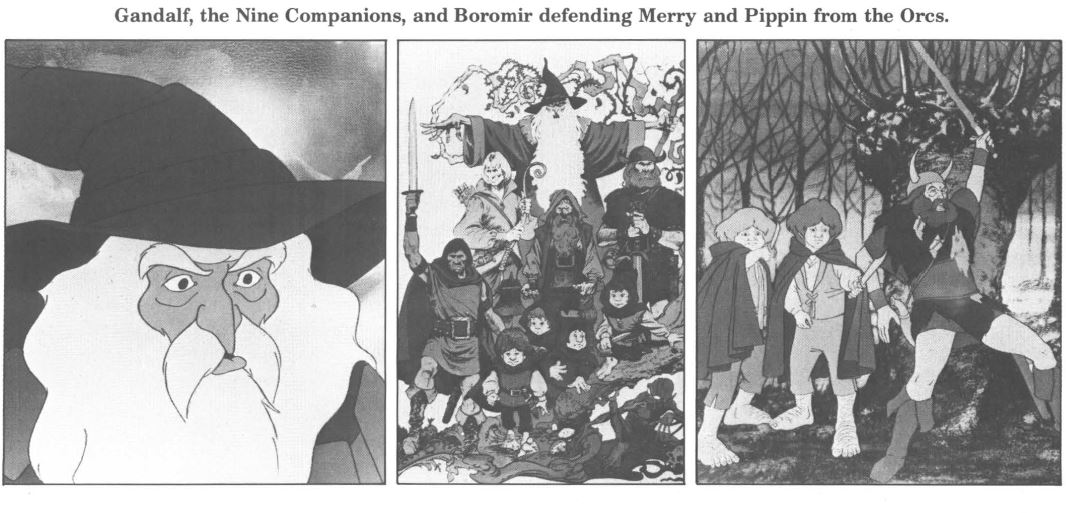

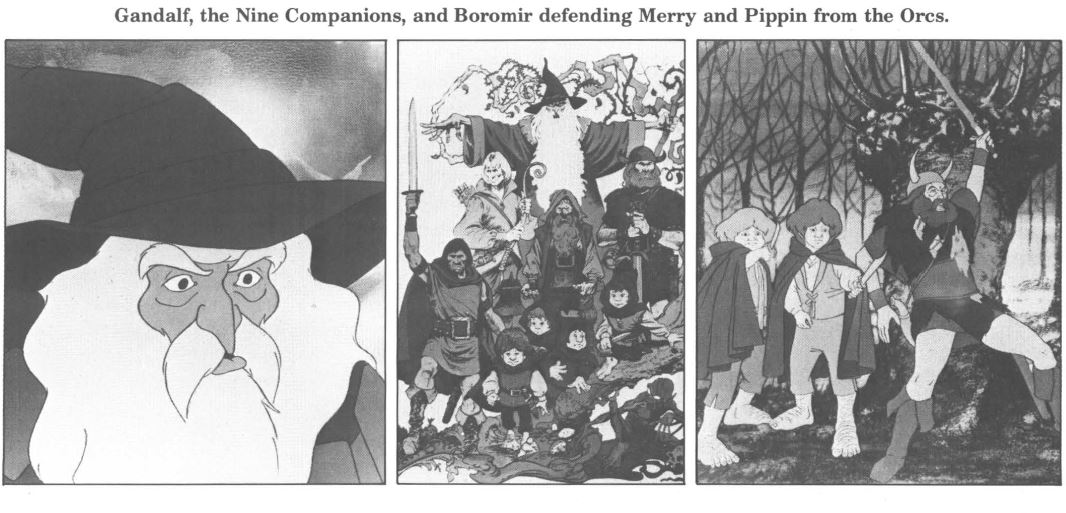

The director’s hand was less sure when it came to characterization. Here all Tolkien fans will disagree with him—and with each other. Who doesn’t have his mental picture of Frodo, Gandalf, Strider, or Treebeard?

I thought that Frodo and Bilbo were approximately in the right spirit. Certainly Gandalf was as wizardly a wizard as Tolkien intended. Strider’s first appearance was as foul as in the original, though once he removed his hood he resembled a Cherokee or a Navajo more than half-man, half-elf. Gollum looked all that he should—gray, slimy, and all stretched out, though his voice did not evoke the same impression. Most animators rely on good voices to make the characters live. Not so with Bakshi. If he had matched good actors with his superb animation techniques, the result would have been unforgettable.

With Sam Gamgee we have a complete misunderstanding of the hobbit Tolkien intended. Bakshi’s Sam is a silly, simpering pudge of a character. Tolkien began with an unsophisticated, though intelligent, gardener, who grew into the ruler of the shire. I realize that Bakshi filmed only the first half of the story, but with such an unfortunate start, how can Sam become what he ought? For much of the original adventure, Sam carries Frodo (emotionally, and, at times, physically). All the animated Sam could carry is his girth.

There are other minor flaws, for example the drawing of Treebeard and the initial appearance of Galadriel. Treebeard should not have a snout, or short, squat legs and long, spindly arms. Galadriel greets the company with eyelashes so thick that it’s a wonder Sam didn’t get out his hedge trimmers. The most beautiful morning star she is not.

Bakshi should have called the film Lord of the Rings, Part One. Then we would have been prepared for the sudden ending—when Gollum decides to take Sam and Frodo to Shelob’s lair. The last line, though, was an appropriate ending for the film. It went something like, “We shall see what more we’ve got in store. Oh, yes, we shall see.”

I wish that Bakshi had emphasized the cosmic nature of the struggle between the allies of the Dark Lord. Without a strong sense of who controls Middle-earth and why Sauron needs to be resisted, the point of the plot gets lost in the superfluity of characters. Tolkien gives us that throughout the story. Bakshi cut most of the dialogue that indicates the religious nature of the conflict. This is no simple war story. The direction should have reinforced that.

Despite all these drawbacks, and I admit there seem to be a great many, the overall impact of the film is a credit to the story (it’s also an entertaining film). An epic, with its overblown language and stock descriptions, almost inevitably fares ill under close scrutiny. The language and structure look sloppy. But relax and take in the atmosphere. The impression will change.

Tolkien created a sweeping history—almost, you might say, a new mythology. He has helped many younger Christians bring new meaning to the phrase “created in the image of God,” as well as to imagination, even to history. Bakshi’s film will bring that tale to people who haven’t read the trilogy. For those who have, it should send them back to the original. It did for me.