Three thousand people pressed close to the smoke-belching train in New York City to greet one of the most exciting figures in the world. It was April, 1917, and evangelist Billy Sunday had arrived to try to bring Jesus Christ to the world’s largest city.

The famous former baseball player had already had a long string of successful campaigns. In Boston 64,000 people had “hit the sawdust trail”; in Philadelphia, 42,000; in Detroit, 27,000; and so the astounding record had gone for seventeen years. Yet many observers were very skeptical about Sunday’s taking on the “Big Apple.” With a cynical press and sophisticated urbanites, could he fill a tabernacle that held 20,000 people for a ten-week crusade?

They underestimated the rapid-fire pulpiteer. While his obvious strength was his speaking ability, his greatest asset was an enormous capacity to organize and publicize. He left very little to chance.

A volunteer ushering staff of 2,500 men had been assembled. A choir of 2,000 had practiced regularly. Churches, factory workers, and women’s groups had been contacted, and arrangements had been made to recognize them during the services. It is estimated that 50,000 volunteers were involved in the effort. Twenty paid assistants were working full-time to tie the package together.

Immense free publicity was generated as the giant tabernacle was built board by board at 168th Street and Broadway. A sounding board was erected over the pulpit to allow Sunday to whisper to 20,000 people without microphone or megaphone. Some Catholic priests and Jewish rabbis held their own rallies to attack the coming crusade. Just in case all this did not cause enough commotion, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., lent Sunday the family public-relations man, the very able Ivy Lee.

Rockefeller did not throw his weight easily into this effort. He had heard of the wild antics and tactics of the evangelist, but he was also aware of his amazing results. What made Rockefeller hesitant were reports that Sunday was amassing a fortune.

This concern was not unfounded. Vast sums had passed through Sunday’s hands. Normally the evangelist answered inquiries about his worth very succinctly: “It’s nobody’s business how much money I have.” Despite this abrasive reply, his financial records were very open.

Early in his career Sunday adopted a practice of designating the last night’s offering for himself. In the small meetings in Nebraska and Kansas he had nearly starved during his first attempts. Now the crowds were considerably larger and the practice was the same. Consequently, people knew exactly what they were giving for, and they gave with abandon. For instance, the total expense of the campaign in Charlotte, North Carolina, was $22,000; Sunday’s “farewell offering” was $26,000. These figures were printed in the local newspaper. In Kansas City he received $32,000; Baltimore, $40,274; Pittsburgh, $46,000. As these figures multiplied, his critics howled. The Tulsa Tribune claimed Sunday was worth over $1.5 million.

Rockefeller, along with a lot of other people, wanted to know if this man were a charlatan and crook, and he privately investigated Sunday’s finances. Sunday passed the examination with excellent grades, and the philanthropist decided to support the crusade openly. We are not sure just what Rockefeller learned, but records show that Sunday gave $100,000 to the Winona Lake Bible Conference and $67,000 to the Pacific Garden Mission.

His detractors were not easily convinced, and Sunday seemed to enjoy the controversy. In great dramatic style he caught the attention of the press again. He announced that he would accept no farewell offering in New York City. Instead, everything above expenses would be given to the Red Cross and the YMCA. As it turned out he handed almost $100,000 over to those organizations.

Rockefeller’s caution turned into enthusiasm. He not only would support the crusade financially but was personally sold on the message Sunday preached. On the morning of the day when the tabernacle was dedicated (April 1) Rockefeller addressed his Bible class, swollen to eight hundred men. He said, “Many men are siding against Mr. Sunday because they dislike his methods, but why should they consider that, so long as he brings men to Christ? Our churches do not lay hold of the masses of the people. If he can touch them, there is just one place for me, and that is at his back.”

That afternoon the governor of New York and Rockefeller joined others on the platform to dedicate the massive tabernacle. Knowing that the nation might go to war any day, Governor Whitman threw out the challenge, “Are we a Christian nation? Are we willing to live up to the religion we profess? Are we willing to die for it?”

To appreciate the New York phenomenon we need to recall the events that were whirling around it. One month before, President Wilson had broken diplomatic relations with Germany. On April 2 the President asked the United States Congress to wage war against German imperialism. On April 4 the Senate adopted a war resolution by a vote of 82–6, and sixteen hours later the House passed the measure 373–50. On Good Friday the President finalized the action. The next day (April 7) Billy Sunday stepped from a train in New York City.

Guarded by 150 police, Sunday was asked if he would support the war. “Help the government, yes sir. Anything that I can do to help the government in any way I’m going to do it. No doubt about it.”

The next day Sunday opened the famous campaign with two services and a total of 40,000 people. “I’ve been preaching for twenty years and I never saw a town with so much vim, ginger, tabasco, and peppermint as little old New York,” he began. And as often happened, the audience was off and cheering. When he attacked the Unitarians or lashed out at the liquor traffic, the gathering resembled a high school pep rally.

Sunday wasted no time getting into the war effort. As a thoroughgoing patriot he promised to help raise 20,000 new recruits to fight the Kaiser. He would tell his audience, “The soldier who breaks every regulation, yet is found on the firing line in the hour of battle, is better than the God-forsaken mutt who won’t even enlist, and does all he can to keep others from enlisting. In these days all are patriots or traitors, to your country and to Jesus Christ.” Then he would jump up on the pulpit and wave the American flag while the comets played and the congregation sang “America.” Often during the early days of a crusade no invitation to receive Christ was given, and Sunday had decided to wait possibly two weeks in New York.

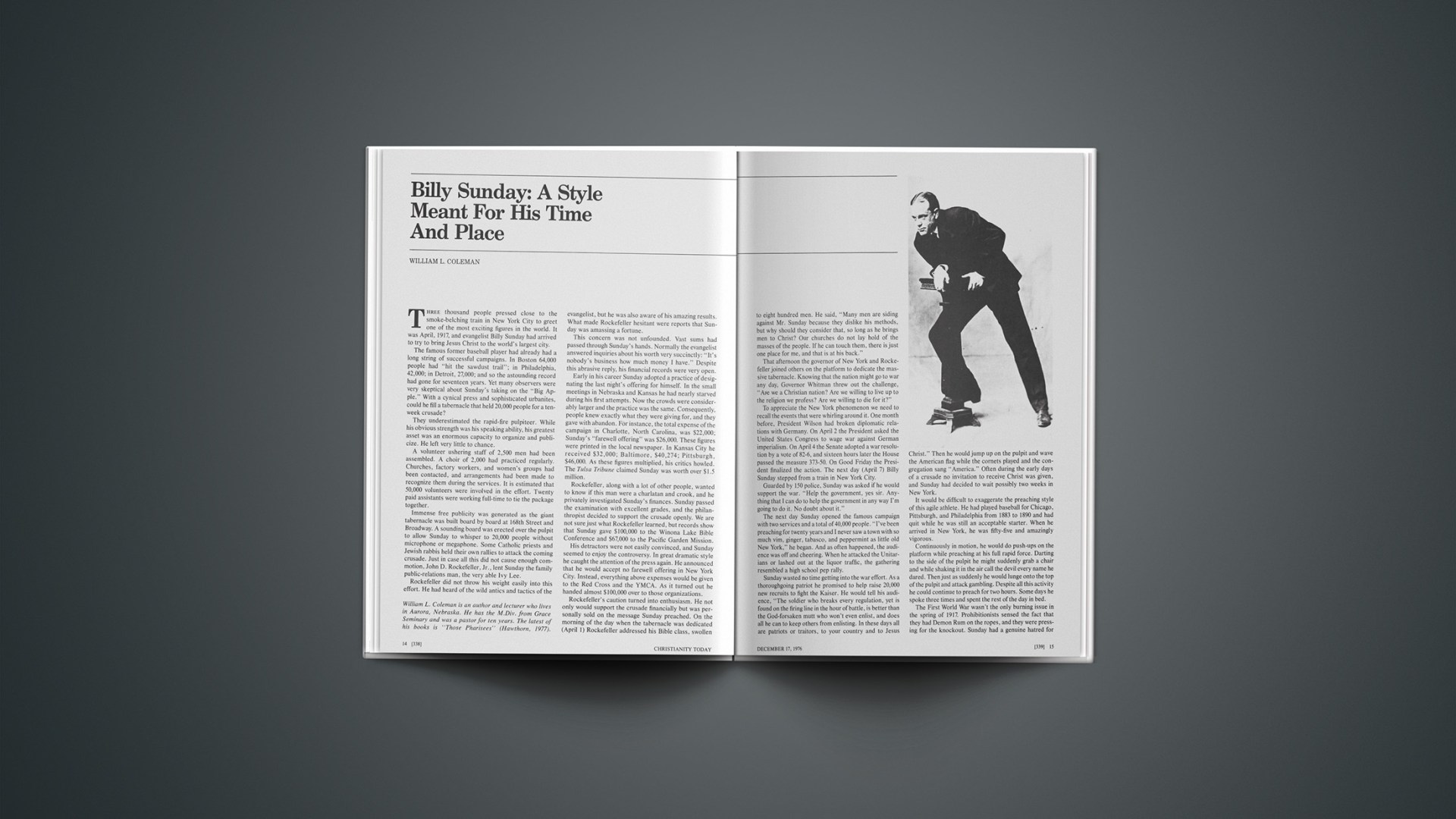

It would be difficult to exaggerate the preaching style of this agile athlete. He had played baseball for Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia from 1883 to 1890 and had quit while he was still an acceptable starter. When he arrived in New York, he was fifty-five and amazingly vigorous.

Continuously in motion, he would do push-ups on the platform while preaching at his full rapid force. Darting to the side of the pulpit he might suddenly grab a chair and while shaking it in the air call the devil every name he dared. Then just as suddenly he would lunge onto the top of the pulpit and attack gambling. Despite all this activity he could continue to preach for two hours. Some days he spoke three times and spent the rest of the day in bed.

The First World War wasn’t the only burning issue in the spring of 1917. Prohibitionists sensed the fact that they had Demon Rum on the ropes, and they were pressing for the knockout. Sunday had a genuine hatred for alcohol, but he also liked to wrap his sermons in the hot issues of the day.

On opening day in New York he served John Barleycorn ample notice: “Whiskey is all right in its place, but its place is in hell. And I want to see everyone put it there as soon as possible. Eighty per cent of all crimes are due to booze; ninety per cent of all the murders are committed under the influence of liquor.” He told his audience that when prohibition was passed in Kansas City in 1905 the bank deposits in the city increased markedly. Alcohol, he said, “eats the carpets off of the floors, the clothes off of your back, your money out of your bank, food off the table, shoes off of the baby’s feet.…”

It would be difficult to convey how powerful Sunday’s famous “Booze Sermon” must have been. Even today, on lifeless paper, without the benefit of Sunday’s powerful personality, the message is very moving. The preacher comes across as articulate, factual, and at the same time emotional enough to be very persuasive. After the Booze Sermon Homer Rodeheaver would lead the congregation in singing “De Brewer’s Big Hosses Can’t Run Over Me.” Probably no one did more to bring in Prohibition than Sunday. When it was finalized in 1920, Sunday was in Norfolk, Virginia. He publicized a mock funeral for John Barleycorn, and 10,000 people came.

In New York Billy Sunday had promised that he would use the same techniques to go after souls that business used for sales. Well over six thousand prayer meetings were held prior to the campaign, and the staff reported an attendance of nearly 80,000. Staff workers held eight or ten meetings each day during the crusade at factories, schools, and offices. All the campaign costs were paid, and most of the $110,000 offering on the final night was given to the YMCA and Red Cross to aid their contribution to the war effort.

On the final day, 25,000 admirers surrounded the tabernacle. The old Literary Digest reported that people “jumped upon the benches, cheered, applauded, waved hats and handkerchiefs, and a mighty chorus of voices took up the shout, ‘Good-by Billy, God bless you.’ ”

Sunday continued on the campaign trail for the next eighteen years. In his seventies he was still speaking but mostly in congregational rather than city-wide crusades. In November, 1935, he died quietly in Chicago.