The Gospel And Architecture

The purpose and duty of a church is to preach the full Gospel, purely and powerfully, and to minister to the needs of its people. But a congregation should also realize that the architecture of its building or buildings is a matter of Gospel.

I don’t wish to imply that the responsibility of a church is to proclaim the virtues of fine building, or that salvation is dependent upon good architecture. Salvation is a free gift of God through faith in Christ. It seems to me, though, that when salvation comes, when our lives are transformed by a renewing of our minds after we have offered our bodies as a living sacrifice to God, as we work out the implications of our salvation, as we grow in the fear and knowledge of the Lord, then all aspects of our lives are subject to renewal: our work, our play, our social lives, even our architecture. This renewal is not a condition for our salvation; it is rather an expression of our thankfulness for it.

Having said all this I want to repeat that the architecture of the Church is neither irrelevant nor unimportant; it is a matter of Gospel. The building that a church occupies and the furnishings within it either reinforce or contradict what the church preaches. I am sure that this is why God himself was the architect of the Tabernacle of the Israelites (Exodus 35 through 39). Architecture is not to be ignored or left only to the elite and artistically sensitive. All Christians should strive to live aesthetically as well as theologically obedient lives as part of their service to God.

There are some signs that churches are increasing in awareness of the relation of church architecture to their message. New church buildings as often as not seat the congregation in circular, semi-circular, and opposing patterns rather than in the traditional parallel rows facing one end of the church. The latter is not unlike a theater where people gather to watch a performance on the stage. No interaction is encouraged between spectators.

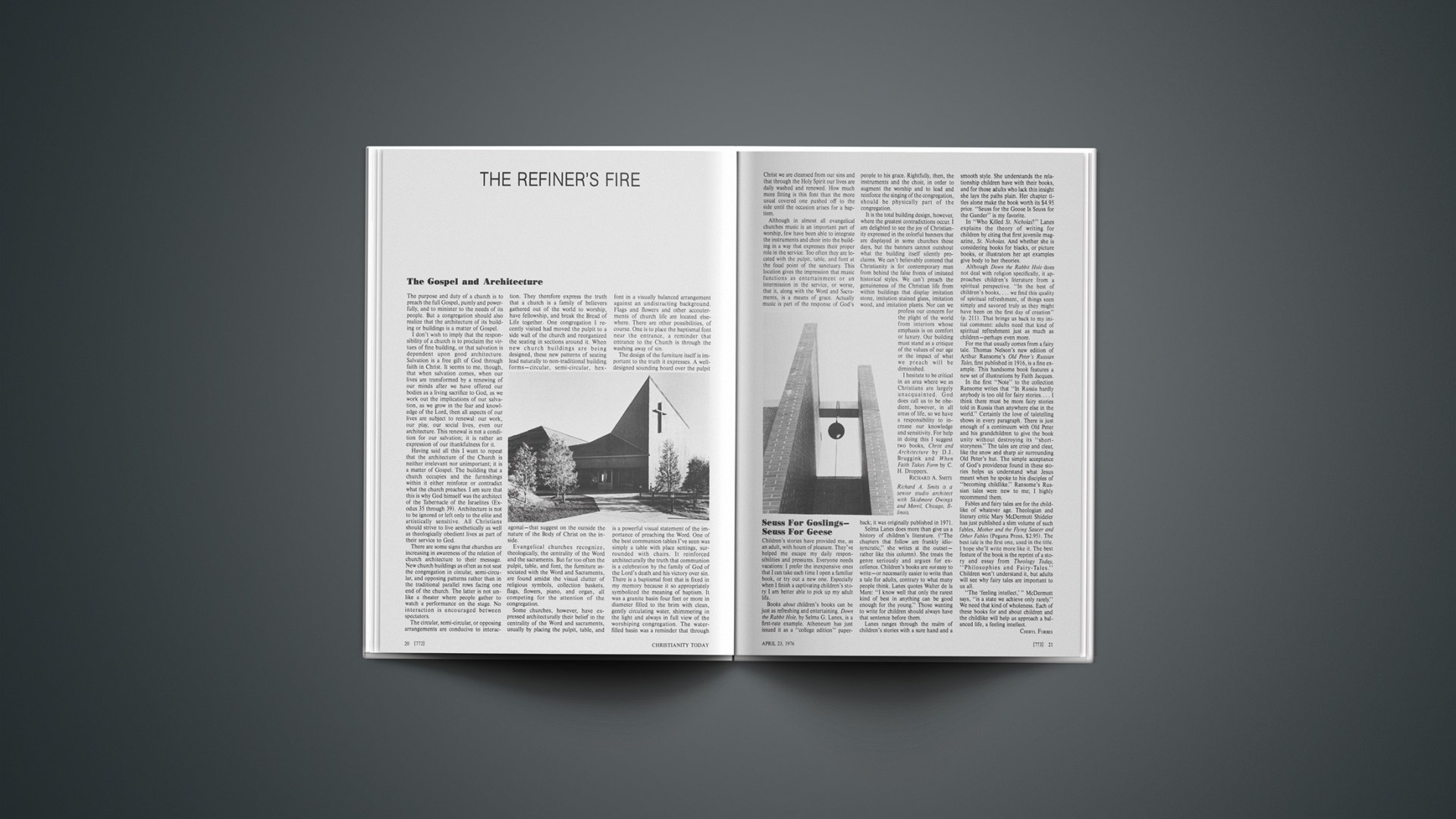

The circular, semi-circular, or opposing arrangements are conducive to interaction. They therefore express the truth that a church is a family of believers gathered out of the world to worship, have fellowship, and break the Bread of Life together. One congregation I recently visited had moved the pulpit to a side wall of the church and reorganized the seating in sections around it. When new church buildings are being designed, these new patterns of seating lead naturally to non-traditional building forms—circular, semi-circular, hexagonal—that suggest on the outside the nature of the Body of Christ on the inside.

Evangelical churches recognize, theologically, the centrality of the Word and the sacraments. But far too often the pulpit, table, and font, the furniture associated with the Word and Sacraments, are found amidst the visual clutter of religious symbols, collection baskets, flags, flowers, piano, and organ, all competing for the attention of the congregation.

Some churches, however, have expressed architecturally their belief in the centrality of the Word and sacraments, usually by placing the pulpit, table, and font in a visually balanced arrangement against an undistracting background. Flags and flowers and other accouterments of church life are located elsewhere. There are other possibilities, of course. One is to place the baptismal font near the entrance, a reminder that entrance to the Church is through the washing away of sin.

The design of the furniture itself is important to the truth it expresses. A well-designed sounding board over the pulpit is a powerful visual statement of the importance of preaching the Word. One of the best communion tables I’ve seen was simply a table with place settings, surrounded with chairs. It reinforced architecturally the truth that communion is a celebration by the family of God of the Lord’s death and his victory over sin. There is a baptismal font that is fixed in my memory because it so appropriately symbolized the meaning of baptism. It was a granite basin four feet or more in diameter filled to the brim with clean, gently circulating water, shimmering in the light and always in full view of the worshiping congregation. The water-filled basin was a reminder that through Christ we are cleansed from our sins and that through the Holy Spirit our lives are daily washed and renewed. How much more fitting is this font than the more usual covered one pushed off to the side until the occasion arises for a baptism.

Although in almost all evangelical churches music is an important part of worship, few have been able to integrate the instruments and choir into the building in a way that expresses their proper role in the service. Too often they are located with the pulpit, table, and font at the focal point of the sanctuary. This location gives the impression that music functions as entertainment or an intermission in the service, or worse, that it, along with the Word and Sacraments, is a means of grace. Actually music is part of the response of God’s people to his grace. Rightfully, then, the instruments and the choir, in order to augment the worship and to lead and reinforce the singing of the congregation, should be physically part of the congregation.

It is the total building design, however, where the greatest contradictions occur. I am delighted to see the joy of Christianity expressed in the colorful banners that are displayed in some churches these days, but the banners cannot outshout what the building itself silently proclaims. We can’t believably contend that Christianity is for contemporary man from behind the false fronts of imitated historical styles. We can’t preach the genuineness of the Christian life from within buildings that display imitation stone, imitation stained glass, imitation wood, and imitation plants. Nor can we profess our concern for the plight of the world from interiors whose emphasis is on comfort or luxury. Our building must stand as a critique of the values of our age or the impact of what we preach will be diminished.

I hesitate to be critical in an area where we as Christians are largely unacquainted. God does call us to be obedient, however, in all areas of life, so we have a responsibility to increase our knowledge and sensitivity. For help in doing this I suggest two books, Christ and Architecture by D.J. Bruggink and When Faith Takes Form by C. H. Droppers.

RICHARD A. SMITS

Richard A. Smits is a senior studio architect with Skidmore Owings and Merril, Chicago, Illinois.

Seuss For Goslings—Seuss For Geese

Children’s stories have provided me, as an adult, with hours of pleasure. They’ve helped me escape my daily responsibilities and pressures. Everyone needs vacations: I prefer the inexpensive ones that I can take each time I open a familiar book, or try out a new one. Especially when I finish a captivating children’s story I am better able to pick up my adult life.

Books about children’s books can be just as refreshing and entertaining. Down the Rabbit Hole, by Selma G. Lanes, is a first-rate example. Atheneum has just issued it as a “college edition” paper-back; it was originally published in 1971.

Selma Lanes does more than give us a history of children’s literature. (“The chapters that follow are frankly idiosyncratic,” she writes at the outset—rather like this column). She treats the genre seriously and argues for excellence. Children’s books are not easy to write—or necessarily easier to write than a tale for adults, contrary to what many people think. Lanes quotes Walter de la Mare: “I know well that only the rarest kind of best in anything can be good enough for the young.” Those wanting to write for children should always have that sentence before them.

Lanes ranges through the realm of children’s stories with a sure hand and a smooth style. She understands the relationship children have with their books, and for those adults who lack this insight she lays the paths plain. Her chapter titles alone make the book worth its $4.95 price. “Seuss for the Goose Is Seuss for the Gander” is my favorite.

In “Who Killed St. Nicholas?” Lanes explains the theory of writing for children by citing that first juvenile magazine, St. Nicholas. And whether she is considering books for blacks, or picture books, or illustrators her apt examples give body to her theories.

Although Down the Rabbit Hole does not deal with religion specifically, it approaches children’s literature from a spiritual perspective. “In the best of children’s books, … we find this quality of spiritual refreshment, of things seen simply and savored truly as they might have been on the first day of creation” (p. 211). That brings us back to my initial comment: adults need that kind of spiritual refreshment just as much as children—perhaps even more.

For me that usually comes from a fairy tale. Thomas Nelson’s new edition of Arthur Ransome’s Old Peter’s Russian Tales, first published in 1916, is a fine example. This handsome book features a new set of illustrations by Faith Jacques.

In the first “Note” to the collection Ransome writes that “In Russia hardly anybody is too old for fairy stories.… I think there must be more fairy stories told in Russia than anywhere else in the world.” Certainly the love of taletelling shows in every paragraph. There is just enough of a continuum with Old Peter and his grandchildren to give the book unity without destroying its “short-storyness.” The tales are crisp and clear, like the snow and sharp air surrounding Old Peter’s hut. The simple acceptance of God’s providence found in these stories helps us understand what Jesus meant when he spoke to his disciples of “becoming childlike.” Ransome’s Russian tales were new to me; I highly recommend them.

Fables and fairy tales are for the childlike of whatever age. Theologian and literary critic Mary McDermott Shideler has just published a slim volume of such fables, Mother and the Flying Saucer and Other Fables (Pegana Press, $2.95). The best tale is the first one, used in the title. I hope she’ll write more like it. The best feature of the book is the reprint of a story and essay from Theology Today, “Philosophies and Fairy-Tales.” Children won’t understand it, but adults will see why fairy tales are important to us all.

“The ‘feeling intellect,’ ” McDermott says, “is a state we achieve only rarely.” We need that kind of wholeness. Each of these books for and about children and the childlike will help us approach a balanced life, a feeling intellect.

CHERYL FORBES