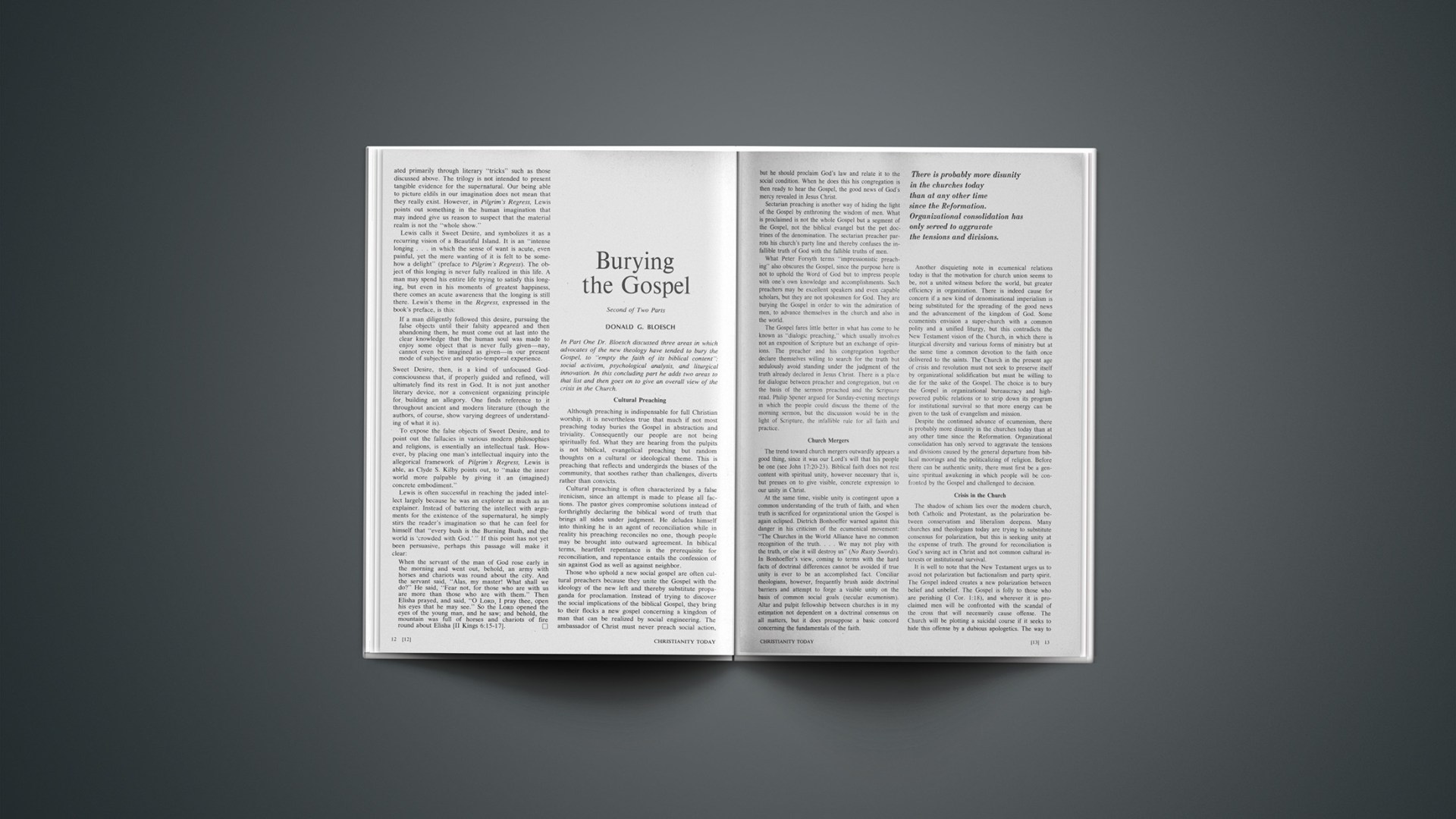

In Part One Dr. Bloesch discussed three areas in which advocates of the new theology have tended to bury the Gospel, to “empty the faith of its biblical content”: social activism, psychological analysis, and liturgical innovation. In this concluding part he adds two areas to that list and then goes on to give an overall view of the crisis in the Church.

Cultural Preaching

Although preaching is indispensable for full Christian worship, it is nevertheless true that much if not most preaching today buries the Gospel in abstraction and triviality. Consequently our people are not being spiritually fed. What they are hearing from the pulpits is not biblical, evangelical preaching but random thoughts on a cultural or ideological theme. This is preaching that reflects and undergirds the biases of the community, that soothes rather than challenges, diverts rather than convicts.

Cultural preaching is often characterized by a false irenicism, since an attempt is made to please all factions. The pastor gives compromise solutions instead of forthrightly declaring the biblical word of truth that brings all sides under judgment. He deludes himself into thinking he is an agent of reconciliation while in reality his preaching reconciles no one, though people may be brought into outward agreement. In biblical terms, heartfelt repentance is the prerequisite for reconciliation, and repentance entails the confession of sin against God as well as against neighbor.

Those who uphold a new social gospel are often cultural preachers because they unite the Gospel with the ideology of the new left and thereby substitute propaganda for proclamation. Instead of trying to discover the social implications of the biblical Gospel, they bring to their flocks a new gospel concerning a kingdom of man that can be realized by social engineering. The ambassador of Christ must never preach social action, but he should proclaim God’s law and relate it to the social condition. When he does this his congregation is then ready to hear the Gospel, the good news of God’s mercy revealed in Jesus Christ.

Sectarian preaching is another way of hiding the light of the Gospel by enthroning the wisdom of men. What is proclaimed is not the whole Gospel but a segment of the Gospel, not the biblical evangel but the pet doctrines of the denomination. The sectarian preacher parrots his church’s party line and thereby confuses the infallible truth of God with the fallible truths of men.

What Peter Forsyth terms “impressionistic preaching” also obscures the Gospel, since the purpose here is not to uphold the Word of God but to impress people with one’s own knowledge and accomplishments. Such preachers may be excellent speakers and even capable scholars, but they are not spokesmen for God. They are burying the Gospel in order to win the admiration of men, to advance themselves in the church and also in the world.

The Gospel fares little better in what has come to be known as “dialogic preaching,” which usually involves not an exposition of Scripture but an exchange of opinions. The preacher and his congregation together declare themselves willing to search for the truth but sedulously avoid standing under the judgment of the truth already declared in Jesus Christ. There is a place for dialogue between preacher and congregation, but on the basis of the sermon preached and the Scripture read. Philip Spener argued for Sunday-evening meetings in which the people could discuss the theme of the morning sermon, but the discussion would be in the light of Scripture, the infallible rule for all faith and practice.

Church Mergers

The trend toward church mergers outwardly appears a good thing, since it was our Lord’s will that his people be one (see John 17:20–23). Biblical faith does not rest content with spiritual unity, however necessary that is, but presses on to give visible, concrete expression to our unity in Christ.

At the same time, visible unity is contingent upon a common understanding of the truth of faith, and when truth is sacrificed for organizational union the Gospel is again eclipsed. Dietrich Bonhoeffer warned against this danger in his criticism of the ecumenical movement: “The Churches in the World Alliance have no common recognition of the truth.… We may not play with the truth, or else it will destroy us” (No Rusty Swords). In Bonhoeffer’s view, coming to terms with the hard facts of doctrinal differences cannot be avoided if true unity is ever to be an accomplished fact. Conciliar theologians, however, frequently brush aside doctrinal barriers and attempt to forge a visible unity on the basis of common social goals (secular ecumenism). Altar and pulpit fellowship between churches is in my estimation not dependent on a doctrinal consensus on all matters, but it does presuppose a basic concord concerning the fundamentals of the faith.

Another disquieting note in ecumenical relations today is that the motivation for church union seems to be, not a united witness before the world, but greater efficiency in organization. There is indeed cause for concern if a new kind of denominational imperialism is being substituted for the spreading of the good news and the advancement of the kingdom of God. Some ecumenists envision a super-church with a common polity and a unified liturgy, but this contradicts the New Testament vision of the Church, in which there is liturgical diversity and various forms of ministry but at the same time a common devotion to the faith once delivered to the saints. The Church in the present age of crisis and revolution must not seek to preserve itself by organizational solidification but must be willing to die for the sake of the Gospel. The choice is to bury the Gospel in organizational bureaucracy and high-powered public relations or to strip down its program for institutional survival so that more energy can be given to the task of evangelism and mission.

Despite the continued advance of ecumenism, there is probably more disunity in the churches today than at any other time since the Reformation. Organizational consolidation has only served to aggravate the tensions and divisions caused by the general departure from biblical moorings and the politicalizing of religion. Before there can be authentic unity, there must first be a genuine spiritual awakening in which people will be confronted by the Gospel and challenged to decision.

Crisis In The Church

The shadow of schism lies over the modern church, both Catholic and Protestant, as the polarization between conservatism and liberalism deepens. Many churches and theologians today are trying to substitute consensus for polarization, but this is seeking unity at the expense of truth. The ground for reconciliation is God’s saving act in Christ and not common cultural interests or institutional survival.

It is well to note that the New Testament urges us to avoid not polarization but factionalism and party spirit. The Gospel indeed creates a new polarization between belief and unbelief. The Gospel is folly to those who are perishing (1 Cor. 1:18), and wherever it is proclaimed men will be confronted with the scandal of the cross that will necessarily cause offense. The Church will be plotting a suicidal course if it seeks to hide this offense by a dubious apologetics. The way to end polarization is by conversion and submission to Jesus Christ, the Lord of the Church.

Liberal theologians never tire of asserting that the crisis today is one of ethical obedience. That the people of God are not obeying his will in the present situation cannot be denied, but behind this disobedience is the deeper crisis of faith. One cannot do the truth unless he is in the truth, and therefore the trumpet of the modern church gives an uncertain sound (cf. 1 Cor. 14:8). Many churches and seminaries today have become fields for evangelism rather than forces of evangelism. This means that apostasy is rife even among the sons of the kingdom. It is well to recognize that unbelief is constantly pictured in the Old Testament as a more heinous sin even than social injustice. The Church has been addressing itself to symptoms and has been ignoring the source of the cancer that afflicts modern society.

New idolatries are emerging to fill the spiritual vacuum created by the Church’s reluctance to let the truth of the Gospel shine into the hearts of men. Among these new objects of deification are the group mind or the social consciousness (as in groupism and progressive education); the nation or race (as in the new nationalism and militarism); the social class (as in Marxism); and the vital instincts (as in pansexualism). The Church today is challenged to unmask these pseudo-gods, but it is greatly hampered in this task by its subservience to ideology, whether of the right or of the left.

Hand in hand with the new idolatries is a new morality that is openly skeptical of any moral absolute and that for all practical purposes serves the technological revolution. The aim of this morality is adjustment to the cultural norm, and its high priests are the social scientists and psychologists. Jacques Ellul is one theologian and social analyst who has been alert to the encroaching danger of a “technological morality,” which, in his words “appears as a suppression of morality through the total absorption of the individual into the group” (To Will and To Do).

A new “democratic” totalitarianism has arisen that seeks to enlist the aid of both the right and the left. Those who give their allegiance to “the rights of man” in the abstract instead of the glory of God and whose slogan is “All power to the people” are unwittingly preparing the way for a totalitarian takeover. They give lip service to the democratic ideal, but in reality the society they envision would be tightly controlled by an oligarchy of sociologists, educationists, and psychologists.

The Church can cope with the present crisis only if it becomes ever more sensitive to social reality by freeing itself from its bondage to ideology. Instead of trying to come to terms with the growing unbelief in our times, it should seek to unmask unbelief as well as proclaim the faith in all its purity and power. It should also be alive to apostasy from within and particularly to the secular humanism that has infiltrated the new social-gospel movement. This kind of humanism is also present in the conciliar movement, as well as in the circles of religious education and pastoral theology. For the sake of true ecumenism and an authentically Christian education, church theologians should begin applying themselves to the task of the defense of the faith within the Church.

What is needed today is a new kind of dogmatics that will at the same time be an apologetics, one that will neither hide nor embellish the Gospel but will confront the world with it. This would be an apologetics in the service of a kerygmatic theology. It would not seek to make the Gospel credible or plausible to the world, but it would not hesitate to expose the pitiful delusions of a great many moderns and the emptiness of their own philosophies in the face of the world crisis.

Martin Marty, rightly I believe, maintains that we are entering an apocalyptic age, an age when the certainties of yesterday will probably be taken from us. The shallow optimism that has permeated secular and political theology will prove insufficient to cope with the harsh realities that lie ahead. Instead of an optimism based on the inherent perfectibility of man and evolutionary progress, the world stands in need of an optimism founded on the divine realities of justification and regeneration. The death of God will be followed by the death of the Church unless the Church abandons the gods of popular culture-religion and begins listening again to the voice of the true God as this is found in Holy Scripture. Then it might rediscover its true role and mission, which is to uphold the glorious Gospel of redemption before a lost and despairing world and thereby prepare the way for the coming kingdom of God.

Another Underground

Thousands of students, laymen, clergymen, and nuns have gone underground in revolt against the traditional structures and forms of their churches.… Basically they seek spiritual renewal and satisfaction for themselves. They hope the wider Church will join their quest. I have found little bitterness among them and almost no inclination to mount a holy war of liberation against the formal church. They are mostly straight Establishment-type people. Unlike the multitudes of hippie converts, these have not dropped out of mainstream society. Many are even in their usual pews and places of service on Sunday—but they also worship with kindred spirits in cell-like meetings later in the week.—EDWARD E. PLOWMAN, The Jesus Movement in America (David C. Cook, 1971), p. 10. Used by permission.