How do you express nonconformity to the world but be involved in world need?

This has been the question for Mennonites since the former followers of Ulrich Zwingli founded the first Anabaptist congregation in 1525. And it is the compelling issue of the day for the younger generation of Mennonites that is wrestling with acculturation, non-resistance, the doctrine of separation of church and state, the social gospel, and evangelism.

“The church hierarchy is attempting to hold the line culturally, but youth are attempting to define their own identity—what it means to be one’s brother in the twentieth century,” said an under-25 spokesman for the (Old) Mennonite Church, the largest of the Mennonite bodies in the United States and Canada.1Among the score of Mennonite bodies in the United States and Canada, the four largest are the (Old) Mennonite Church, with 94,755 baptized members; the General Conference Mennonite, 55,034; the Mennonite Brethren, 31,780; and the Old Order Amish Mennonites, 23,025. Altogether, the Mennonite movement has about 250,000 adherents in the United States and Canada and another 250,000 in the rest of the world. The very traditional, German-speaking, non-missionary-sending Amish are to be clearly distinguished from the other bodies. They are the unreconciled descendants of a division dating back to the 1690s in Switzerland. “Our parents are concerned we might be involved in the world,” continued Stuart Showalter, public relations director of Eastern Mennonite College, one of the denomination’s two college-seminary combinations. “We are concerned we might not be involved at the right point. Our parents were concerned we would be contaminated; we seek contamination and we seek to eliminate it.”

Mennonites have been in hot water over the church-state issue ever since they disagreed with Zwingli (and Calvin and Luther), maintaining that relationships between the government and established religion should be minimal. They have also insisted that only adult believers be baptized, repudiated the sacramental view of Communion, and plugged for the “simple faith” of the New Testament Church.

Their stand on these and other matters, such as the rejection of physical force, made the earliest Mennonites unpopular in Protestant and Catholic countries of Europe alike. After bloody and vicious persecution (5,000 Anabaptists were martyred in Europe in a ten-year period), a band of survivors fled to North Germany. They were led by a former Catholic priest named Menno Simons, from whom the Mennonites derived their name.

William Penn, Quaker founder of Pennsylvania, was instrumental in assisting Mennonite immigrants to settle there beginning in 1683. Waves of Mennonites came from Europe during the first three decades of the eighteenth century, and Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, is still the world’s largest and most varied Mennonite center. Some 43,600 adherents of the Mennonite community live there, according to a recent newspaper survey.

By general Protestant standards, Mennonite worship is plain, even austere. In theology, although there are differences between the various Mennonite branches, conservative and evangelical—if not fundamentalistic—doctrine prevails. Except in the most conservative wings, this theology is coupled with a strong social consciousness. “We found our stride in evangelicalism,” avers Dr. Myron Augsburger, president of Eastern Mennonite College and an internationally known evangelist (see story adjoining).

Mennonites are also strong in missions, having one of the highest ratios of missionaries to supporting members of any denominational family. A worldwide relief ministry is conducted through the Mennonite Central Committee, an inter-Mennonite service agency. Generous giving is required for such a small body to support this extensive work. (The average member of the Mennonite Church gave $151.78 last year, or 5.4 per cent of his income.)

Because the pattern has been for Mennonite ministers to make their living from secular work, very small congregations can subsist. Example: the twenty-seven-member Detroit (Michigan) Mennonite Church—the only one in the city—is self-supporting.

Mennonites lead the way among evangelicals in certain evangelism techniques. The Mennonite Broadcasting Institute (MBI) produces programs for 459 stations. Short, specialized programs dropped in the midst of secular programming—to catch the unchurched—have proven successful lately. “We get by the station’s gatekeeping of putting religious programs in religious time blocs, and we get by the built-in systems people have to turn religion off,” explained MBI’s head, Kenneth Weaver, in an interview. The programs, like the popular “Heart-to-Heart” homemaking broadcast (185 stations carry it) give the listener useful information for everyday living laced with a spiritual message.

Mennonite bookrack evangelism is unique among church programs. About twenty of the Mennonite Church’s district mission boards buy religious books and racks through the MBI at a hefty discount. The books are sold in 314 racks placed in places like supermarkets, variety and department stores, and airport concession stands. Last year more than 100,000 books were moved through this ministry.

Because Mennonites are opposed to all war, alternate programs to military service have become a Mennonite distinctive. Several of the most popular are the Teachers Abroad Program, a three-year assignment in underdeveloped countries; PAX, an overseas technical aid program in community development; and Voluntary Service, a program to serve minority groups and inner city needs in the United States.

Ironically, it was World War II that spurred the breakdown in the traditionally rigid Mennonite style of dress and general separation from the outside world. Alternate service for draft-age Mennonite men formed a beachhead to the outside, and higher education came to be more accepted. During the late forties and the fifties, Mennonite youth felt a “shade of embarrassment” and inferiority about their essentially rural background, according to David Augsburger, speaker on the Mennonite Hour. “Now, Mennonite youth are proud of their background,” he added.

Acculturation among Mennonite groups that had not previously accepted it picked up speed in the sixties. During the last five years, student attire at Eastern Mennonite College in Harrisonburg, Virginia, has changed drastically. “When you see the kids walk down the street in town now, you can’t tell any difference between them and non-Mennonites,” noted a young Mennonite.

Since the vogue of the peace movement and resistance to the draft, Mennonite youth have suddenly found that their centuries-old position grooves nicely with mainline young people. “Relating to race, social problems, and war has given us an appeal to a lot of people who feel this—plus a spiritual dimension with Christ—is lacking in their churches,” declares Dr. Myron Augsburger.

Although the trend is away from emphasis on dress (the cape dress and head covering for women and the plain coat for men), there is an ultra-traditional strand that opposes modernization. Some Mennonite congregations have withdrawn from their conferences over the issue, and others, like the West Valley District of the Virginia Conference of the Mennonite Church, appear to be near doing so.

“If you get rid of the bonnets, you can win these people,” a student once told Harry Brunk, 72, retired history professor at Eastern Mennonite. But, speaking of an evangelism effort in a high-rise apartment area of Ontario, Canada, the student later related: “We got rid of the bonnets and we aren’t winning them.”

Although arguments over dress appear to be one of the biggest hang-ups among Mennonites, the articulate younger brood sees the real issues elsewhere. This was well illustrated in the baccalaureate address given at Eastern Mennonite last May by Conrad G. Brunk, a Wheaton College graduate and former philosophy instructor at EMC. Said Brunk, 25, now assistant director of the National Service Board for Religious Objectors in Washington, D.C.:

“It is clear that the old form of nonconformity in mere outward appearance can no longer revitalize the church today—to return to it or to attempt to preserve the old forms would lead us to a certain institutional death.… Nonconformity in our age must be an active nonconformism that does not grow out of a sentimental adherence to mere tradition, but out of a renewed sensitivity to the needs of the world around us.… a witness that breaks through all the facades and niceties by which a society covers over its evils.”

RUSSELL CHANDLER

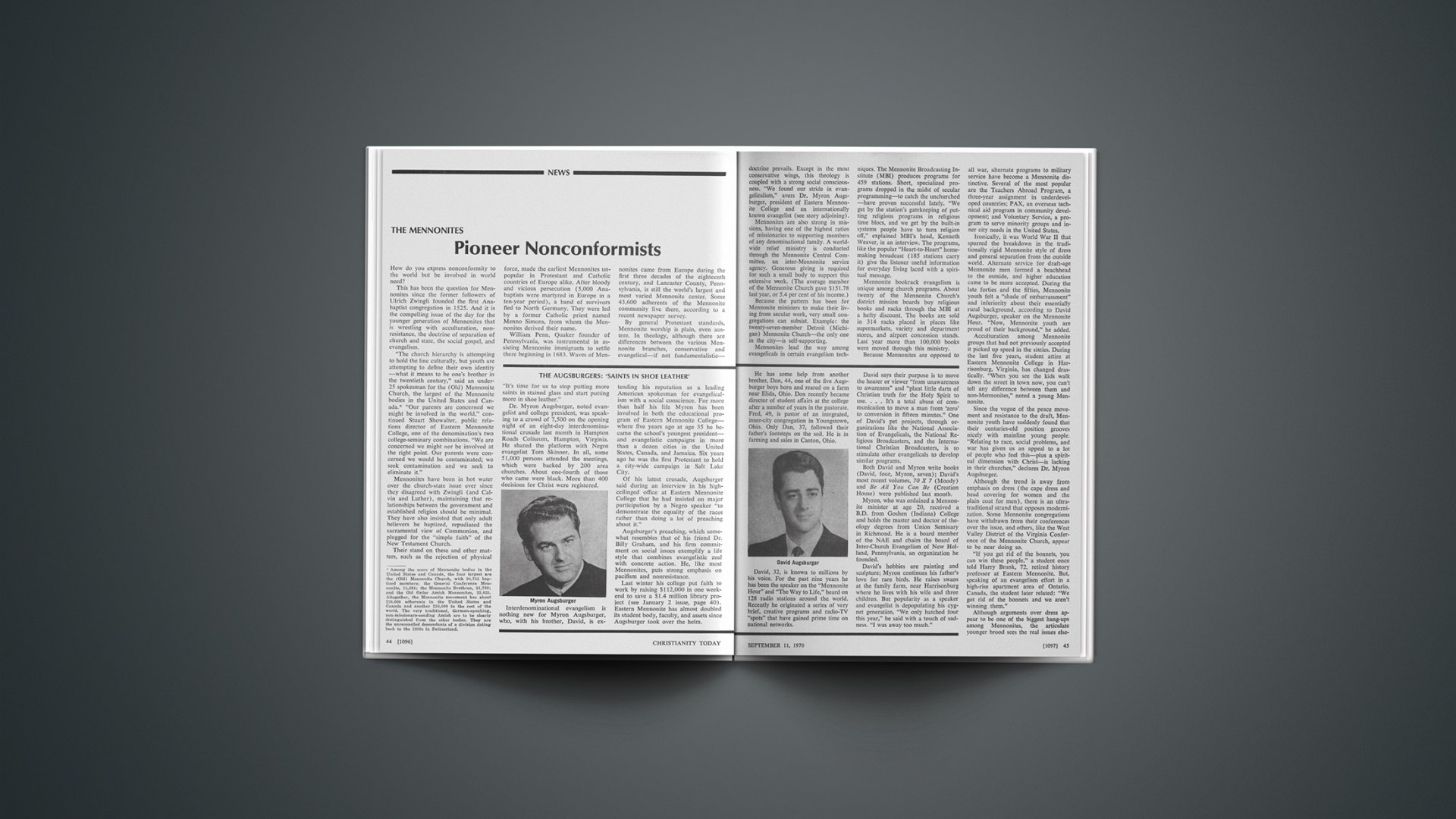

The Augsburgers: ‘Saints In Shoe Leather’

“It’s time for us to stop putting more saints in stained glass and start putting more in shoe leather.”

Dr. Myron Augsburger, noted evangelist and college president, was speaking to a crowd of 7,500 on the opening night of an eight-day interdenominational crusade last month in Hampton Roads Coliseum, Hampton, Virginia. He shared the platform with Negro evangelist Tom Skinner. In all, some 51,000 persons attended the meetings, which were backed by 200 area churches. About one-fourth of those who came were black. More than 400 decisions for Christ were registered.

Interdenominational evangelism is nothing new for Myron Augsburger, who, with his brother, David, is extending his reputation as a leading American spokesman for evangelicalism with a social conscience. For more than half his life Myron has been involved in both the educational program of Eastern Mennonite College—where five years ago at age 35 he became the school’s youngest president—and evangelistic campaigns in more than a dozen cities in the United States, Canada, and Jamaica. Six years ago he was the first Protestant to hold a city-wide campaign in Salt Lake City.

Of his latest crusade, Augsburger said during an interview in his high-ceilinged office at Eastern Mennonite College that he had insisted on major participation by a Negro speaker “to demonstrate the equality of the races rather than doing a lot of preaching about it.”

Augsburger’s preaching, which somewhat resembles that of his friend Dr. Billy Graham, and his firm commitment on social issues exemplify a life style that combines evangelistic zeal with concrete action. He, like most Mennonites, puts strong emphasis on pacifism and nonresistance.

Last winter his college put faith to work by raising $112,000 in one weekend to save a $1.4 million library project (see January 2 issue, page 40). Eastern Mennonite has almost doubled its student body, faculty, and assets since Augsburger took over the helm.

He has some help from another brother, Don, 44, one of the five Augsburger boys born and reared on a farm near Elida, Ohio. Don recently became director of student affairs at the college after a number of years in the pastorate. Fred, 49, is pastor of an integrated, inner-city congregation in Youngstown, Ohio. Only Dan, 37, followed their father’s footsteps on the soil. He is in farming and sales in Canton, Ohio.

David, 32, is known to millions by his voice. For the past nine years he has been the speaker on the “Mennonite Hour” and “The Way to Life,” heard on 128 radio stations around the world. Recently he originated a series of very brief, creative programs and radio-TV “spots” that have gained prime time on national networks.

David says their purpose is to move the hearer or viewer “from unawareness to awareness” and “plant little darts of Christian truth for the Holy Spirit to use.… It’s a total abuse of communication to move a man from ‘zero’ to conversion in fifteen minutes.” One of David’s pet projects, through organizations like the National Association of Evangelicals, the National Religious Broadcasters, and the International Christian Broadcasters, is to stimulate other evangelicals to develop similar programs.

Both David and Myron write books (David, four, Myron, seven); David’s most recent volumes, 70 X 7 (Moody) and Be All You Can Be (Creation House) were published last month.

Myron, who was ordained a Mennonite minister at age 20, received a B.D. from Goshen (Indiana) College and holds the master and doctor of theology degrees from Union Seminary in Richmond. He is a board member of the NAE and chairs the board of Inter-Church Evangelism of New Holland, Pennsylvania, an organization he founded.

David’s hobbies are painting and sculpture; Myron continues his father’s love for rare birds. He raises swans at the family farm, near Harrisonburg where he lives with his wife and three children. But popularity as a speaker and evangelist is depopulating his cygnet generation. “We only hatched four this year,” he said with a touch of sadness. “I was away too much.”

Evangelism Consultation

The first major evangelism conference for all Mennonites since 1530 will be held in Chicago April 13–16, 1972. Dr. Myron S. Augsburger, evangelist and president of Eastern Mennonite College in Harrisonburg, Virginia, announced the all-Mennonite Consultation on Evangelism last month. He is chairman of the consultation steering committee.

The gathering is an outgrowth of the Berlin and Minneapolis congresses on evangelism, Augsburger said. At least ten of the nation’s Mennonite denominations are expected to send representatives.

Augsburger said goals of the consultation include establishing a common ground among Mennonites for evangelism, and advancing the distinctiveness of Mennonite discipleship as a pattern for the “larger church.” “Many thoughtful evangelicals are urging us to speak up, to share our concepts of discipleship,” Augsburger added.