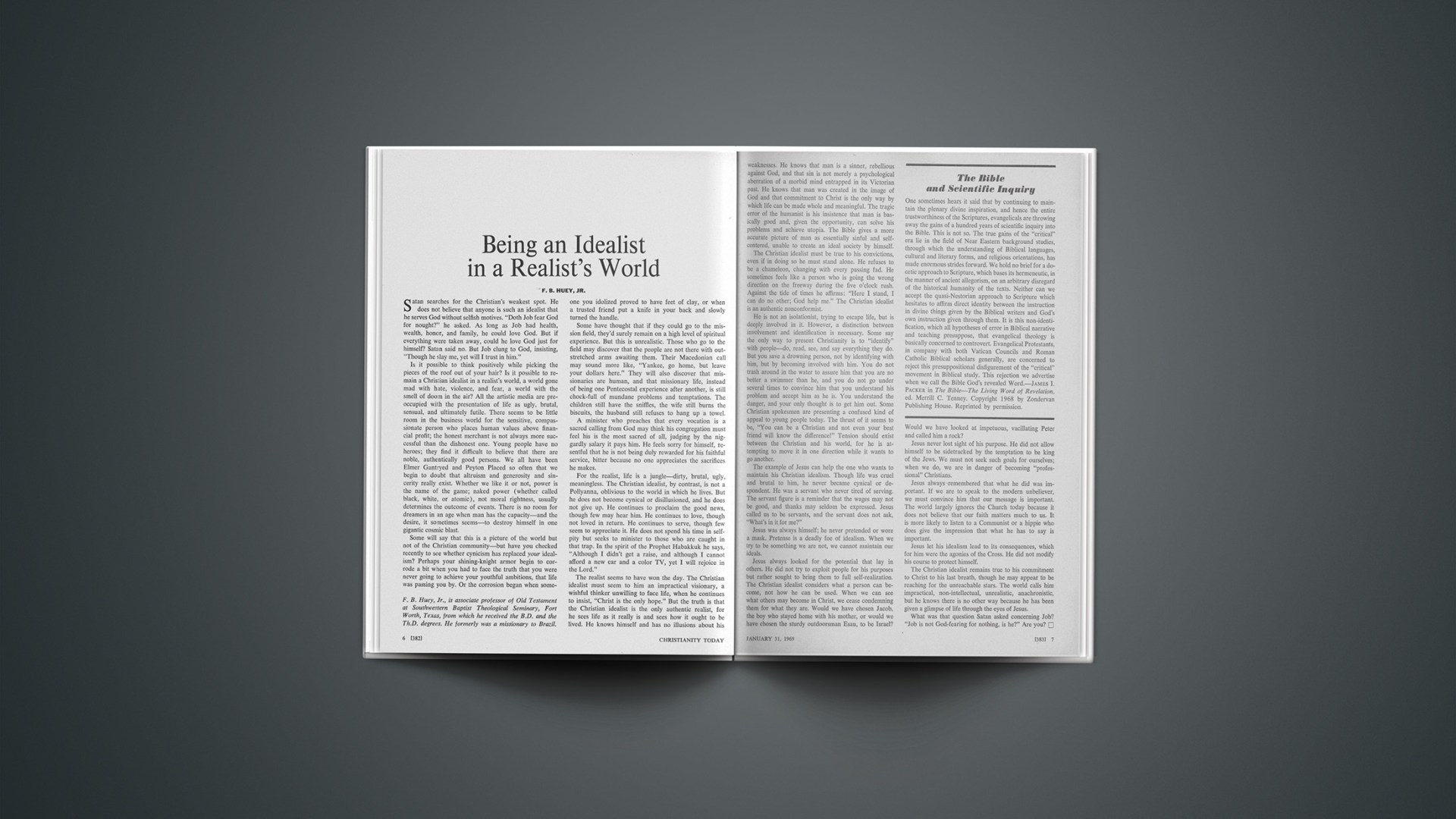

Satan searches for the Christian’s weakest spot. He does not believe that anyone is such an idealist that he serves God without selfish motives. “Doth Job fear God for nought?” he asked. As long as Job had health, wealth, honor, and family, he could love God. But if everything were taken away, could he love God just for himself? Satan said no. But Job clung to God, insisting, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him.”

Is it possible to think positively while picking the pieces of the roof out of your hair? Is it possible to remain a Christian idealist in a realist’s world, a world gone mad with hate, violence, and fear, a world with the smell of doom in the air? All the artistic media are preoccupied with the presentation of life as ugly, brutal, sensual, and ultimately futile. There seems to be little room in the business world for the sensitive, compassionate person who places human values above financial profit; the honest merchant is not always more successful than the dishonest one. Young people have no heroes; they find it difficult to believe that there are noble, authentically good persons. We all have been Elmer Gantryed and Peyton Placed so often that we begin to doubt that altruism and generosity and sincerity really exist. Whether we like it or not, power is the name of the game; naked power (whether called black, white, or atomic), not moral rightness, usually determines the outcome of events. There is no room for dreamers in an age when man has the capacity—and the desire, it sometimes seems—to destroy himself in one gigantic cosmic blast.

Some will say that this is a picture of the world but not of the Christian community—but have you checked recently to see whether cynicism has replaced your idealism? Perhaps your shining-knight armor begin to corrode a bit when you had to face the truth that you were never going to achieve your youthful ambitions, that life was passing you by. Or the corrosion began when someone you idolized proved to have feet of clay, or when a trusted friend put a knife in your back and slowly turned the handle.

Some have thought that if they could go to the mission field, they’d surely remain on a high level of spiritual experience. But this is unrealistic. Those who go to the field may discover that the people are not there with outstretched arms awaiting them. Their Macedonian call may sound more like, “Yankee, go home, but leave your dollars here.” They will also discover that missionaries are human, and that missionary life, instead of being one Pentecostal experience after another, is still chock-full of mundane problems and temptations. The children still have the sniffles, the wife still burns the biscuits, the husband still refuses to hang up a towel.

A minister who preaches that every vocation is a sacred calling from God may think his congregation must feel his is the most sacred of all, judging by the niggardly salary it pays him. He feels sorry for himself, resentful that he is not being duly rewarded for his faithful service, bitter because no one appreciates the sacrifices he makes.

For the realist, life is a jungle—dirty, brutal, ugly, meaningless. The Christian idealist, by contrast, is not a Pollyanna, oblivious to the world in which he lives. But he does not become cynical or disillusioned, and he does not give up. He continues to proclaim the good news, though few may hear him. He continues to love, though not loved in return. He continues to serve, though few seem to appreciate it. He does not spend his time in self-pity but seeks to minister to those who are caught in that trap. In the spirit of the Prophet Habakkuk he says, “Although I didn’t get a raise, and although I cannot afford a new car and a color TV, yet I will rejoice in the Lord.”

The realist seems to have won the day. The Christian idealist must seem to him an impractical visionary, a wishful thinker unwilling to face life, when he continues to insist, “Christ is the only hope.” But the truth is that the Christian idealist is the only authentic realist, for he sees life as it really is and sees how it ought to be lived. He knows himself and has no illusions about his weaknesses. He knows that man is a sinner, rebellious against God, and that sin is not merely a psychological aberration of a morbid mind entrapped in its Victorian past. He knows that man was created in the image of God and that commitment to Christ is the only way by which life can be made whole and meaningful. The tragic error of the humanist is his insistence that man is basically good and, given the opportunity, can solve his problems and achieve utopia. The Bible gives a more accurate picture of man as essentially sinful and self-centered, unable to create an ideal society by himself.

The Christian idealist must be true to his convictions, even if in doing so he must stand alone. He refuses to be a chameleon, changing with every passing fad. He sometimes feels like a person who is going the wrong direction on the freeway during the five o’clock rush. Against the tide of times he affirms: “Here I stand, I can do no other; God help me.” The Christian idealist is an authentic nonconformist.

He is not an isolationist, trying to escape life, but is deeply involved in it. However, a distinction between involvement and identification is necessary. Some say the only way to present Christianity is to “identify” with people—do, read, see, and say everything they do. But you save a drowning person, not by identifying with him, but by becoming involved with him. You do not trash around in the water to assure him that you are no better a swimmer than he, and you do not go under several times to convince him that you understand his problem and accept him as he is. You understand the danger, and your only thought is to get him out. Some Christian spokesmen are presenting a confused kind of appeal to young people today. The thrust of it seems to be, “You can be a Christian and not even your best friend will know the difference!” Tension should exist between the Christian and his world, for he is attempting to move it in one direction while it wants to go another.

The example of Jesus can help the one who wants to maintain his Christian idealism. Though life was cruel and brutal to him, he never became cynical or despondent. He was a servant who never tired of serving. The servant figure is a reminder that the wages may not be good, and thanks may seldom be expressed. Jesus called us to be servants, and the servant does not ask, “What’s in it for me?”

Jesus was always himself; he never pretended or wore a mask. Pretense is a deadly foe of idealism. When we try to be something we are not, we cannot maintain our ideals.

Jesus always looked for the potential that lay in others. He did not try to exploit people for his purposes but rather sought to bring them to full self-realization. The Christian idealist considers what a person can become, not how he can be used. When we can see what others may become in Christ, we cease condemning them for what they are. Would we have chosen Jacob, the boy who stayed home with his mother, or would we have chosen the sturdy outdoorsman Esau, to be Israel? Would we have looked at impetuous, vacillating Peter and called him a rock?

Jesus never lost sight of his purpose. He did not allow himself to be sidetracked by the temptation to be king of the Jews. We must not seek such goals for ourselves; when we do, we are in danger of becoming “professional” Christians.

Jesus always remembered that what he did was important. If we are to speak to the modern unbeliever, we must convince him that our message is important. The world largely ignores the Church today because it does not believe that our faith matters much to us. It is more likely to listen to a Communist or a hippie who does give the impression that what he has to say is important.

Jesus let his idealism lead to, its consequences, which for him were the agonies of the Cross. He did not modify his course to protect himself.

The Christian idealist remains true to his commitment to Christ to his last breath, though he may appear to be reaching for the unreachable stars. The world calls him impractical, non-intellectual, unrealistic, anachronistic, but he knows there is no other way because he has been given a glimpse of life through the eyes of Jesus.

What was that question Satan asked concerning Job? “Job is not God-fearing for nothing, is he?” Are you?

The Bible and Scientific Inquiry

One sometimes hears it said that by continuing to maintain the plenary divine inspiration, and hence the entire trustworthiness of the Scriptures, evangelicals are throwing away the gains of a hundred years of scientific inquiry into the Bible. This is not so. The true gains of the “critical” era lie in the field of Near Eastern background studies, through which the understanding of Biblical languages, cultural and literary forms, and religious orientations, has made enormous strides forward. We hold no brief for a docetic approach to Scripture, which bases its hermeneutic, in the manner of ancient allegorism, on an arbitrary disregard of the historical humanity of the texts. Neither can we accept the quasi-Nestorian approach to Scripture which hesitates to affirm direct identity between the instruction in divine things given by the Biblical writers and God’s own instruction given through them. It is this non-identification, which all hypotheses of error in Biblical narrative and teaching presuppose, that evangelical theology is basically concerned to controvert. Evangelical Protestants, in company with both Vatican Councils and Roman Catholic Biblical scholars generally, are concerned to reject this presuppositional disfigurement of the “critical” movement in Biblical study. This rejection we advertise when we call the Bible God’s revealed Word.—JAMES I. PACKER in The Bible—The Living Word of Revelation, ed. Merrill C. Tenney. Copyright 1968 by Zondervan Publishing House. Reprinted by permission.