The Answer To Irrationalism

Set Forth Your Case, by Clark Pinnock (Craig, 1967, 94 pp., $1.50), is reviewed, by Robert L. Cleath, assistant editor,CHRISTIANITY TODAY.

Many men of our day, bound by the strait jacket of antisupernatural thought, are coming to believe that life is absurd. In a desperate quest to find meaning and satisfaction, they are retreating into the catacombs of subjective irrationalism. To show contemporaries that irrationalism and despair need not plague men and that the Gospel of Christ offers a sure hope based on substantial evidence, Clark Pinnock has written this brief, scintillating apologetic work, Set Forth Your Case.

This thirty-year-old theologian from New Orleans Baptist Seminary considers apologetics—the defense of the truthfulness of the Christian religion—an indispensable tool for evangelism. Its intent, he claims, is “not to coerce people to accept the Christian faith but to make it possible for them to do so intelligently. The data we possess about the gospel is sufficient to make it sensible for the non-Christian to begin his search for the ultimate clue with Christianity.” Although he is aware that without the convicting and illuminating action of the Holy Spirit even the soundest apologetic has no power to make a man a Christian, Pinnock rests his case on the historical events and biblical revelation that provide a rational basis for Christianity. He refuses to surrender the belief that “the heart cannot delight in what the mind rejects as false.”

Pinnock presents his apologetic against the backdrop of current humanistic philosophy and theology. He claims that modern theology has sold out to a philosophical irrationalism that separates the “lower story” of reason, fact, and history from the “upper story” of intuition, faith, and conjecture. The Bible is placed in the lower story while the non-verbal “work of God” occupies the upper story, where “encounter with God” takes place. Meaning is found apart from fact. The subject who has faith becomes more important than the object of his faith. Ambiguous and solipsistic, modern theology turns away from evidences, claims Pinnock, and thus destroys the vital means of challenging the non-Christian to believe in Jesus Christ.

Evangelical Christians, for whom the personal experience of grace is a reality, are cautioned by Pinnock not to allow the subjective validating process of the new liberalism to become the basis for establishing the truthfulness of the Gospel. He states, “The uniqueness of the Christian message is not found at the point of experience at all but in the incarnation datum.” Biblical faith is not a leap in the dark but a response motivated by the revealed promises of God. Pinnock recognizes the necessary role that spiritual experience plays in personal verification: “Apart from the work of the Spirit the gospel itself could only be truth on ice, cold and fruitless.” But he maintains that the deep joy yielded by the Gospel is related to its truthfulness.

Presenting his positive case for Christianity, Pinnock discusses topics crucial for today: the historical reliability of the New Testament; the identity, claims, and miracles of Jesus Christ; evidences for the resurrection; the indispensability of the propositional revelation of Scripture to sound theology; the knowledge of God; the mythology of evolution; and the need for well-trained, articulate apologists to invade all of human culture. His discussions of these topics are too brief. Yet his lines of argument and selective evidence ignite the mind and make one realize that his arguments merit serious consideration by all truth-seekers.

Pinnock advances his position on key topics in full view of competing contemporary views. Before considering Christ’s identity, he sets forth the reasons why the old and new “quests for the historical Jesus” have failed. The old quest rightly used inductive methodology but failed because it limited Jesus strictly to his human proportions. The new quest’s fallacy is that it retains a naturalistic bias and rejects the inductive procedure. Resting his case on New Testament evidence, Pinnock asserts that Jesus is readily approachable. The evidence shows him to be the Messiah, human and divine. Pinnock refers to Jesus’ personal claims, his authority, his miracles, and his work of redemption. He argues that the evidence obligates men to acknowledge Jesus either as a criminal megalomaniac or as the Messiah he claimed to be.

The young Baptist theologian sees the bodily resurrection of Christ as central to the integrity of the Saviour and the Gospel. He considers current thought that bases knowledge of the resurrection strictly on “immediate” experience as a departure from the apostolic proclamation that pointed both to historical evidence and spiritual awareness. Succinctly and effectively he recites evidence for the resurrection: the empty tomb, the conduct of Christ’s opponents and apostles, the appearances, the subsequent ministry of the Church. He concludes, “The resurrection stands within the realm of historical factuality.”

The brevity with which Pinnock has treated his themes precludes recognition of this work as a landmark volume in apologetics. Yet he has enunciated the approach needed for a generation that is rebelling against sham. His bare-knuckles challenge of current leading theological ideas will be cheered by people who possess but cannot adequately articulate a disdain for the irrational aberrations sweeping through the ecclesiastical intelligentsia. His forthright, well-reasoned advocacy of the historic Christian position will provoke the uncommitted to consider the claims of the Gospel. And the committed who absorb Pinnock’s arguments will be better able to set forth their case for Christ. His selective bibliography will point readers toward a deeper study of apologetics than this short, easily read book allows.

Christians need to heed Pinnock’s insistence that the Gospel be presented in a rationally compelling manner. He states: “The notion that nobody is ever converted to Christ by argument is a foolish platitude.” He is right. In our intellect-oriented age that is fast succumbing to irrational philosophies, Spirit-filled Christians must be equipped with sound arguments based on biblical revelation and historical evidence in order to register a powerful witness for Jesus Christ. Laymen would do well to study the case set forth by Pinnock. Those who do are bound to become more effective Christian persuaders.

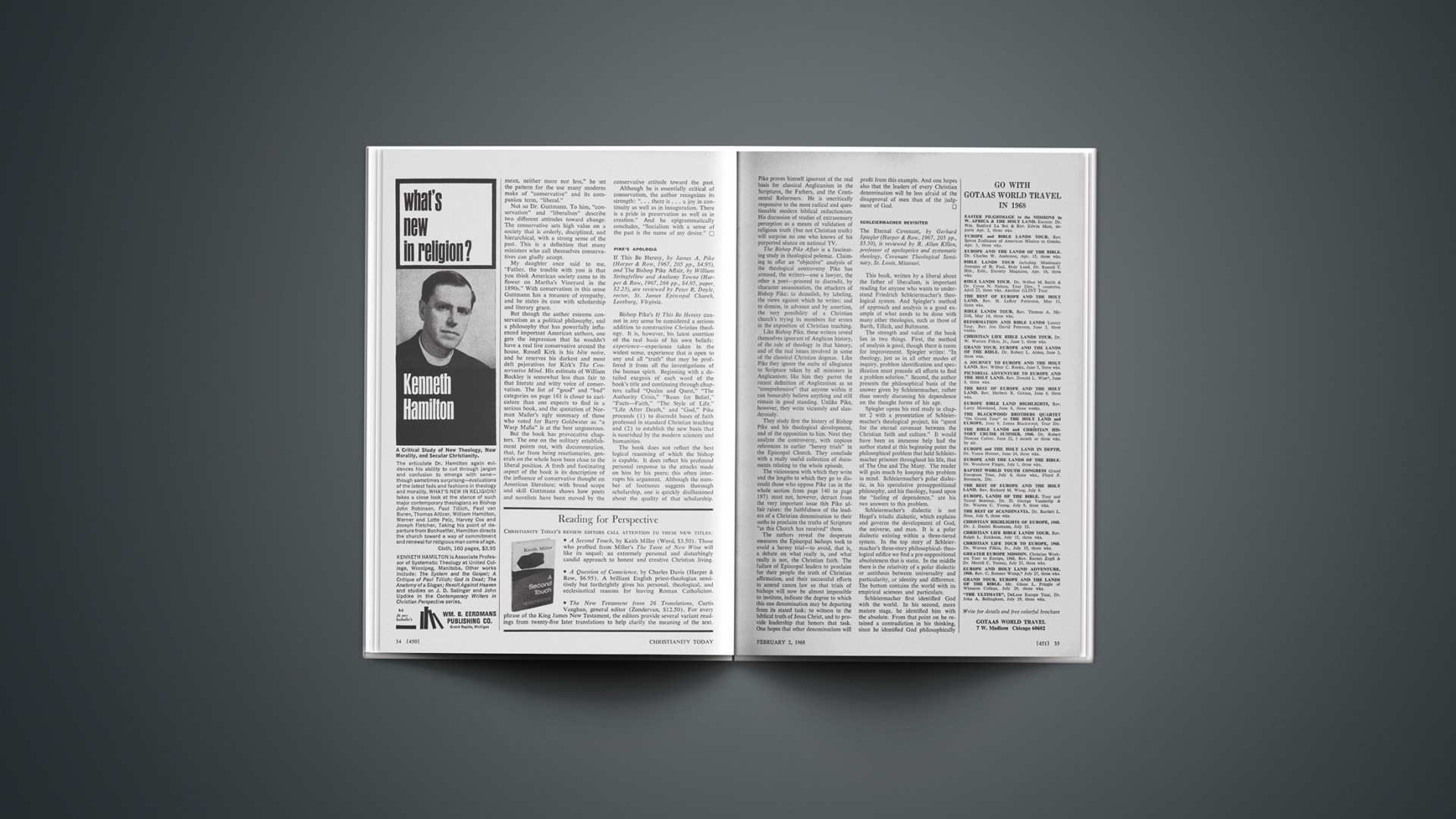

Kirk, Buckley, And The ‘Wasp Mafia’

The Conservative Tradition in America, by Allen Guttmann (Oxford, 1967, 214 pp., $6), is reviewed by Harry R. Butman, editor, “The Congregationalist,” and pastor, Congregational Church of the Messiah, Los Angeles, California.

Although few pastors will be able to appreciate fully the glittering expertise with which Dr. Guttmann handles a host of obscure political theorists, many will thank him for coming up with an acceptable definition of “conservative.” When, in Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty scornfully informed Alice that when he used a word, “it means precisely what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less,” he set the pattern for the use many moderns make of “conservative” and its companion term, “liberal.”

Not so Dr. Guttmann. To him, “conservatism” and “liberalism” describe two different attitudes toward change. The conservative sets high value on a society that is orderly, disciplined, and hierarchical, with a strong sense of the past. This is a definition that many ministers who call themselves conservatives can gladly accept.

My daughter once said to me, “Father, the trouble with you is that you think American society came to its flower on Martha’s Vineyard in the 1890s.” With conservatism in this sense Guttmann has a measure of sympathy, and he states its case with scholarship and literary grace.

But though the author esteems conservatism as a political philosophy, and a philosophy that has powerfully influenced important American authors, one gets the impression that he wouldn’t have a real live conservative around the house. Russell Kirk is his bête noire, and he reserves his darkest and most deft pejoratives for Kirk’s The Conservative Mind. His estimate of William Buckley is somewhat less than fair to that literate and witty voice of conservatism. The list of “good” and “bad” categories on page 161 is closer to caricature than one expects to find in a serious book, and the quotation of Norman Mailer’s ugly summary of those who voted for Barry Goldwater as “a Wasp Mafia” is at the best ungenerous.

But the book has provocative chapters. The one on the military establishment points out, with documentation, that, far from being reactionaries, generals on the whole have been close to the liberal position. A fresh and fascinating aspect of the book is its description of the influence of conservative thought on American literature; with broad scope and skill Guttmann shows how poets and novelists have been moved by the conservative attitude toward the past.

Although he is essentially critical of conservatism, the author recognizes its strength: “… there is … a joy in continuity as well as in inauguration. There is a pride in preservation as well as in creation.” And he epigrammatically concludes, “Socialism with a sense of the past is the name of my desire.”

Pike’S Apologia

If This Be Heresy, by James A. Pike (Harper & Row, 1967, 205 pp., $4.95), and The Bishop Pike Affair, by William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne (Harper & Row, 1967, 266 pp., $4.95, paper, $2.25), are reviewed by Peter R. Doyle, rector, St. James Episcopal Church, Leesburg, Virginia.

Bishop Pike’s If This Be Heresy cannot in any sense be considered a serious addition to constructive Christian theology. It is, however, his latest assertion of the real basis of his own beliefs: experience—experience taken in the widest sense, experience that is open to any and all “truth” that may be proffered it from all the investigations of the human spirit. Beginning with a detailed exegesis of each word of the book’s title and continuing through chapters called “Qualm and Quest,” “The Authority Crisis,” “Bases for Belief,” “Facts—Faith,” “The Style of Life,” “Life After Death,” and “God,” Pike proceeds (1) to discredit bases of faith professed in standard Christian teaching and (2) to establish the new basis that is nourished by the modern sciences and humanities.

Reading For Perspective

CHRISTIANITY TODAY’S REVIEW EDITORS CALL ATTENTION TO THESE NEW TITLES:

• A Second Touch, by Keith Miller (Word, $3.50). Those who profited from Miller’s The Taste of New Wine will like its sequel: an extremely personal and disturbingly candid approach to honest and creative Christian living.

• A Question of Conscience, by Charles Davis (Harper & Row, $6.95). A brilliant English priest-theologian sensitively but forthrightly gives his personal, theological, and ecclesiastical reasons for leaving Roman Catholicism.

• The New Testament from 26 Translations, Curtis Vaughan, general editor (Zondervan, $12.50). For every phrase of the King James New Testament, the editors provide several variant readings from twenty-five later translations to help clarify the meaning of the text.

The book does not reflect the best logical reasoning of which the bishop is capable. It does reflect his profound personal response to the attacks made on him by his peers; this often interrupts his argument. Although the number of footnotes suggests thorough scholarship, one is quickly disillusioned about the quality of that scholarship. Pike proves himself ignorant of the real basis for classical Anglicanism in the Scriptures, the Fathers, and the Continental Reformers. He is uncritically responsive to the most radical and questionable modern biblical reductionism. His discussion of studies of extrasensory perception as a means of validation of religious truth (but not Christian truth) will surprise no one who knows of his purported séance on national TV.

The Bishop Pike Affair is a fascinating study in theological polemic. Claiming to offer an “objective” analysis of the theological controversy Pike has aroused, the writers—one a lawyer, the other a poet—proceed to discredit, by character assassination, the attackers of Bishop Pike; to demolish, by labeling, the views against which he writes; and to dismiss, in advance and by assertion, the very possibility of a Christian church’s trying its members for errors in the exposition of Christian teaching.

Like Bishop Pike, these writers reveal themselves ignorant of Anglican history, of the role of theology in that history, and of the real issues involved in some of the classical Christian dogmas. Like Pike they ignore the oaths of allegiance to Scripture taken by all ministers in Anglicanism; like him they parrot the recent definition of Anglicanism as so “comprehensive” that anyone within it can honorably believe anything and still remain in good standing. Unlike Pike, however, they write viciously and slanderously.

They study first the history of Bishop Pike and his theological development, and of the opposition to him. Next they analyze the controversy, with copious references to earlier “heresy trials” in the Episcopal Church. They conclude with a really useful collection of documents relating to the whole episode.

The viciousness with which they write and the lengths to which they go to discredit those who oppose Pike (as in the whole section from page 140 to page 197) must not, however, detract from the very important issue this Pike affair raises: the faithfulness of the leaders of a Christian denomination to their oaths to proclaim the truths of Scripture “as this Church has received” them.

The authors reveal the desperate measures the Episcopal bishops took to avoid a heresy trial—to avoid, that is, a debate on what really is, and what really is not, the Christian faith. The failure of Episcopal leaders to proclaim for their people the truth of Christian affirmation, and their successful efforts to amend canon law so that trials of bishops will now be almost impossible to institute, indicate the degree to which this one denomination may be departing from its stated task: to witness to the biblical truth of Jesus Christ, and to provide leadership that honors that task. One hopes that other denominations will profit from this example. And one hopes also that the leaders of every Christian denomination will be less afraid of the disapproval of men than of the judgment of God.

Schleiermacher Revisited

The Eternal Covenant, by Gerhard Spiegler (Harper & Row, 1967, 205 pp., $5.50), is reviewed by R. Allan Killen, professor of apologetics and systematic theology, Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri.

This book, written by a liberal about the father of liberalism, is important reading for anyone who wants to understand Friedrich Schleiermacher’s theological system. And Spiegler’s method of approach and analysis is a good example of what needs to be done with many other theologies, such as those of Barth, Tillich, and Bultmann.

The strength and value of the book lies in two things. First, the method of analysis is good, though there is room for improvement. Spiegler writes: “In theology, just as in all other modes of inquiry, problem identification and specification must precede all efforts to find a problem solution.” Second, the author presents the philosophical basis of the answer given by Schleiermacher, rather than merely discussing his dependence on the thought forms of his age.

Spiegler opens his real study in chapter 2 with a presentation of Schleiermacher’s theological project, his “quest for the eternal covenant between the Christian faith and culture.” It would have been an immense help had the author stated at this beginning point the philosophical problem that held Schleiermacher prisoner throughout his life, that of The One and The Many. The reader will gain much by keeping this problem in mind. Schleiermacher’s polar dialectic, in his speculative presuppositional philosophy, and his theology, based upon the “feeling of dependence,” are his two answers to this problem.

Schleiermacher’s dialectic is not Hegel’s triadic dialectic, which explains and governs the development of God, the universe, and man. It is a polar dialectic existing within a three-tiered system. In the top story of Schleiermacher’s three-story philosophical-theological edifice we find a pre-suppositional absoluteness that is static. In the middle there is the relativity of a polar dialectic or antithesis between universality and particularity, or identity and difference. The bottom contains the world with its empirical sciences and particulars.

Schleiermacher first identified God with the world. In his second, more mature stage, he identified him with the absolute. From that point on he retained a contradiction in his thinking, since he identified God philosophically with the absolute—which separated him entirely from the world—but theologically with Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit, as the presence of God in the Church. Spiegler says that he should have identified God with the second story; then he could have admitted that universals and particulars exist in tension in both God and the world. In Schleiermacher’s philosophy, God is absolutely other and as good as dead. But one who reads his theology finds that he is alive!

The explanation of the tensional polar dialectic present in the second story of Schleiermacher’s system—and also in existence—throws much light upon the presence of the ontological elements of individualization and participation, form and dynamics, destiny and freedom, in Paul Tillich’s theology. The “theological project” of the eternal covenant between Christian faith and culture reveals the origin of Tillich’s view of “The Theology of Culture.”

Denuding A Vital Concept

Messianic Theology and Christian Faith, by George A. Riggan (Westminster, 1967, 208 pp., $6), is reviewed by Charles Lee Feinberg, Talbot Theological Seminary, La Mirada, California.

This important volume contains lectures delivered by George A. Riggan, Riley Professor of Systematic Theology at Hartford Seminary Foundation, to Protestant chaplains in the Far East, and then to groups of laymen and college students in this country. His subject is the historical meaning of the fact that one was called the Messiah and, by implication, the significance of being a Christian.

Riggan moves ably from the messianic kingship in ancient Israel and in Hebrew prophecy, through the beginnings of ecclesiastical messianism and apocalyptic messianism, to New Testament messianism. He first explores the meaning of the term “messiah,” finding that it does not move away from its etymological meaning of “anointed one.” At the beginning it was used to denote the ruling king in Israel. After the exile in Babylon, royal messianism was replaced by priestly messianism. Only with the advent of apocalypticism did messianism come to signify a supernatural and preexistent person through whom God would bring in his eternal kingdom in another world.

When Riggan comes to New Testament messianism, he finds he cannot apply to Jesus the four messianic titles—Christos, Son of Man, Servant of God, Son of God. Why? Because they all emanate from a post-Easter theology, he says, in which the minimal facts of the Gospel were reconstructed by the community of the faithful. Riggan’s final emphasis is that somehow in the life and work of Jesus there is a release of therapeutic energies that can have meaning for us today. His thinking always converges on “the time being.”

I find myself in disagreement with Riggan’s basic postulate, that the messiah concept was at the beginning related only to the anointed king. That it was so used, and even of Gentiles like Cyrus, there is no denying. But surely the Old Testament makes it clear that the technical and eschatological use of the term did not await the rise of apocalypticism or the appearance of the canonical Daniel or the non-canonical Enoch and related works. To denude the term of this vital element is to do harm to the entire discussion.

Furthermore, Riggan seriously overuses the idea of Israel’s borrowing from her neighbors; one is left with the impression that practically nothing was original in Israel. The author constantly questions Old Testament sources, but not on the basis of better evidence. He feels that the descriptions of many events are based on a distortion of facts. Throughout he shows an anti-supernatural bias. He takes great liberties in interpreting Scriptures; for example, can one legitimately accuse Jeremiah of “delusions of grandeur” and “theological megalomania”? Ill-founded criticism is seen in such verdicts as his denial of historicity of the man Daniel and of the authenticity of the greater part of the Synoptic contribution. Somehow, he nevertheless claims, the theologies about Jesus release healing energies that are of great benefit to us today. It is well and good to interpret Second Corinthians 5:19 as “God is the reintegration of fragmented human existence”—but how, Dr. Riggan, how?

Where Parents Go Wrong

Parents on Trial, by David Wilkerson with Claire Cox (Hawthorn, 1967, 188 pp., $4.95), is reviewed by Paul Rader, director, Reality Evangelism, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Why did our child go wrong? Where did we fail? What should we do? These questions plague many parents. Parents on Trial, by Teen Challenge founder David Wilkerson, is one of the sources of practical answers. No mere survey or digest of answers and formulas, the book is based on the experiences, hopes, and heartbreaks of the author’s ministry to teen-age gangs in New York slums.

Wilkerson warns his reader, “You will not like everything you read. Much of it is not very pretty, and some may be shocking.” But the stark fact remains: “Delinquency and drug addiction can strike any home.” Why kids go wrong or right is the responsibility of the parents, says Wilkerson, because “every word and deed is a fiber woven into the character of a child, which ultimately determines how that child fits into the fabric of society.” The evidences of what he calls “potluck parents” are seen, he says, in our jails, street gangs, and mental hospitals, in the rising rates of drug addiction, illegitimacy, alcoholism, divorce, and homosexuality.

Accounts of actual cases illustrate twelve readable chapters: “Six Dead”; “But I Was a Good Mother”; “Why Some Kids Have Given Up on Parents”; “The ‘Hidden’ Delinquents”; “Part-time Parents”; “Like Father Like Son”; “Danger Ahead—Watch the Signs!”; “Homosexuality Starts at Home”; “The ‘Other Half of Illegitimacy”; “God Is for Squares”; “Life Without Father—Exceptions to the Rule”; and “They Are Your Kids, Wrong—Or Right.”

Worth rereading and remembering are his lists of “Ten Ways to Produce a Delinquent,” six factors that contribute to drug addiction, warning signs of drug addiction, and the causes of homosexuality. The scriptural passages he discusses should be studied prayerfully.

Wilkerson’s conclusions are hopeful: “The course of a child’s life can be favorably influenced by parents of any educational or economic standing if they are not afraid to work at being good parents.… Devoted, dedicated, hard-working mothers and fathers can weigh the balance in favor of decency and the building of moral character.”

For parents, this book should be required reading. Others who would do well to read it are ministers, teachers, social workers, judges, policemen, lawyers—and also children. It is both disturbing and encouraging, critical and helpful, shocking and hopeful.

Twice Hanged In Effigy

William Anderson Scott, No Ordinary Man, by Clifford Merrill Drury (Arthur H. Clark, 1967, 352 pp., $6.50), is reviewed by Ilion T. Jones, professor emeritus of practical theology, San Francisco Theological Seminary, San Francisco, California.

This is biography at its best. Its author is a distinguished teacher of church history who is a master at portraying important personages of the past within the social and intellectual currents of their day, and making them and the issues in which they were involved come to life again.

The subject of this study is a colorful Presbyterian minister of the Civil War period who held pastorates in New Orleans, New York City, and San Francisco. He became personally involved in nearly all the stirring issues of those difficult days, and his positive, advanced, often unpopular positions resulted in many tense situations in his churches and in the cities where he lived. Twice in San Francisco he was hanged in effigy.

But his strong Christian character carried him through these unpleasant experiences, and he managed to hold the respect and affection of the great majority of the people. He was given the highest office in his denomination, the moderatorship of the Presbyterian General Assembly. He left as a legacy to the future a college, a theological seminary (now San Francisco Theological Seminary), a journal of religion of some importance, and an outstanding example of ability, efficiency, courage, and integrity.

Dr. Drury is right. William Anderson Scott was “no ordinary man.”

The Highest Aspiration

Make Love Your Aim, by Eugenia Price (Zondervan, 1967, 191 pp., $3.95), is reviewed by Margaret Johnston Hess, minister’s wife and Bible class teacher, Livonia, Michigan.

This is one of those delightful books that agree with what you already think but push it a little bit further. Most of the ideas you could have figured out yourself if you’d stopped to think—but the author did stop to think, and there it is all set down for you, neatly, logically, practically.

Miss Price explains the framework of her discussion—that God is love, and all love is of God. At one point she seems to be backing off the liberal end of things theologically, until she briskly supports her thesis with chapter and verse from First John. Her interpretations of Scripture are fresh and unfettered by ordinary conservative thought-patterns, yet wholly legitimate. Some are like a breath of fresh air in a closed room.

“We show love, true love, when we concern ourselves first and always with the way the other person feels—not with how that other person is making us feel,” she says. Love is what keeps utter personal freedom in check. “God is love and love is man’s deepest need, and therefore when man meets God, man’s deepest need is met.” “We can only learn of love as we learn of God.”

Love-giving is even more important than love-getting. We can learn to love—by practicing. True love frees rather than binds. The love that is God-love is thinking and acting toward other human beings in terms of their own good.

This book is less personal, more objective than some of Miss Price’s earlier books. It is practical, easy to read, and fast moving. For the person who feels he knows all about love, it effectively articulates what usually is in the realm of intuition. For having trouble with love, it could be an invaluable gift, pointing the way to Christ through our need to love and be loved.

Book Briefs

Jesus, edited by Hugh Anderson (Prentice-Hall, 1967, 182 pp., $4.95). A sampler of 19th and 20th century views of Jesus based on different approaches to the Gospels. Includes writings by Bornkamm, Goguel, Renan, Strauss, Schweitzer, Harnack, Bultmann, and others.

Paul and the Agon Motif, by Victor C. Pfitzner (Brill, 1967, 232 pp., 28 guilders). A scholarly study of Paul’s use of the athletic metaphor, a traditional concept perhaps adopted from its use in Hellenistic synagogues.

Instrument of Thy Peace, by Alan Paton (Seabury Press, 1968, 124 pp., $3.50). The author of Cry, the Beloved Country has written a book “for sinners, for those who with all their hearts wish to be better, purer, less selfish, more useful” based on the prayer of St. Francis of Assisi.

Religion and Modern Man, by John B. Magee (Harper & Row, 1967, 510 pp., $8). A stimulating, objective college textbook that introduces the student to live religious options in the world today.

The Two Swords, by Donald E. Boles (Iowa State University, 1967, 831 pp., $10.95). A comprehensive study of the debate over religion in the schools in which the significant court cases and reaction to them are considered.

On Judaism, by Martin Buber (Schocken Books, 1967, 242 pp., $5.95). Addresses by the perceptive Jewish scholar from two periods 1909–1918 and 1939–1951. He calls upon Jews to “await the voice of God whether it comes out of the storm or out of the stillness that follows it.”

Selected Writings of Martin Luther, edited by Theodore G. Tappert (Fortress, 1967, 4 vols., 484 pp., 408 pp., 483 pp. and 403 pp., $2.95 ea.). This four-volume library of important selections from Luther’s writings, arranged chronologically, is a good buy for students of Reformation theology.

Answers To Eutychus Iii’S Quiz

(1) Homer A. Rodeheaver; trombone. (2) Father Divine. (3) Human government. (4) Harry Emerson Fosdick. (5) A stone commemorating God’s help (1 Sam. 7:12). (6) Father Charles Coughlin. (7) Aimee Semple McPherson. (8) William Randolph Hearst. (9) By the Bible concordance they used: Strong’s for the strong; Young’s for the young; Cruden’s for the crude. (10) Oral Roberts; by placing their hands on the radio or TV; to obtain healing.