This is what is written: that the Messiah is to suffer death and to rise from the dead on the third day, and that in his name repentance bringing the forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed to all nations.

—Jesus Christ

(Luke 24:46, 47, NEB)

Not many rocky hillsides are emblazoned with “Jesus Saves” any more. There are fewer tent meetings and sawdust trails. Altar calls in evangelical churches are probably hitting a new low this year.

To some Christians, these are ominous trends of spiritual decay. To others they are evidence of a blessed revolution in biblical evangelism. Traditional evangelistic methods based on hit-or-miss, take-it-or-leave-it proclamation of the Gospel are seen to be giving way to more specialized, in-depth approaches. Evangelicals in North America and abroad are realizing anew that deeds are fully as important as words, that positive dialogue is more effective than legalistic argumentation, and that winning converts is not primarily the task of paid clergymen.

In the spring of 1966, the revolution in evangelism was evident in an assortment of cultural patterns:

At Daytona Beach, Florida, two Bob Jones University-trained folk singers roamed the sands with an inter-religious entertainment and evangelism team during Easter week. Many hundreds of the 75,000 vacationing college students were counseled, and some (including at least one Hebrew) professed initial commitment to Christ. At Fort Lauderdale, some 250 miles south, where thousands of other students were soaking in the sun, an Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship team set up an evangelistic effort.

In New York, Pentecostalist youth worker David Wilkerson planned to open a new training program for converts this week. His Teen Challenge organization, meanwhile, has begun holding Saturday night rallies at a theater on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

In Colorado, evangelist Jack Wyrtzen conducted a three-day camp retreat attended by cadets of the Air Force Academy. A spokesman for Wyrtzen said “many cadets responded to the gospel invitation to receive Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour.”

Fresh approaches notwithstanding, the prospect of mass “revival” seems as remote as ever, at least in the sense of a dynamic, overt phenomenon. Untold numbers of rank-and-file evangelicals are still apathetic toward the evangelistic mandate. The indifference is stiffened by some of the very spokesmen for evangelism, who, despite their verbalizations, do little by way of personal example in winning commitments to Christ.

The current revolution in evangelism, however, may make some important inroads on the problem of non-involvement and unconcern, and the world may yet see a quiet awakening with more long-range impact than the much-publicized revivals of bygone days.

If local churches are able to get over the barrier that the old way is the only way, they may become party to just such a quiet awakening. But as of now, many traditionalists are skeptical about Christian witness within the framework of a fashion show, or Sunday morning coffee hours, or dialogues with homosexuals.

The most crucial issue facing evangelism today, however, lies with its definition. Ecclesiastical and theological liberals are attempting to redefine the term to fit universalistic presuppositions. Under the assumption that all men are already saved, the new evangelism often boils down to a mere effort to make men aware of it. Energies are then shifted toward a change of social structures.

In mainstream denominations and in the major ecumenical organizations, considerable attention is being given to the necessity of new institutional forms in the churches. One debate in this area promised to be waged this week at the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U. S. (Southern) at Montreat, North Carolina. The big topic of conversation before the assembly was a controversial, twenty-seven-page committee report, “New Wine Skins?”

“The history of God’s people reveals a perennial unwillingness to assume the burden of ministering to a changing world,” the report declares. “So it is with our Church today, which is failing to minister like Christ the Servant to the persons of the hungry, the naked, and the oppressed, a fact which must cause us to question seriously whether our denomination is aware of its true mission.”

The report raises the question of the mission of the Church and evangelism but does not attempt to give explicit answers.

Evangelicals, in and out of the mainline denominations, tend to accept the definition of evangelism generally associated with the late Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple, who died in 1944:

“To evangelize is so to present Christ Jesus in the power of the Holy Spirit, that men shall come to put their trust in God through him, to accept him as their Saviour, and serve him as their King in the fellowship of his Church.”

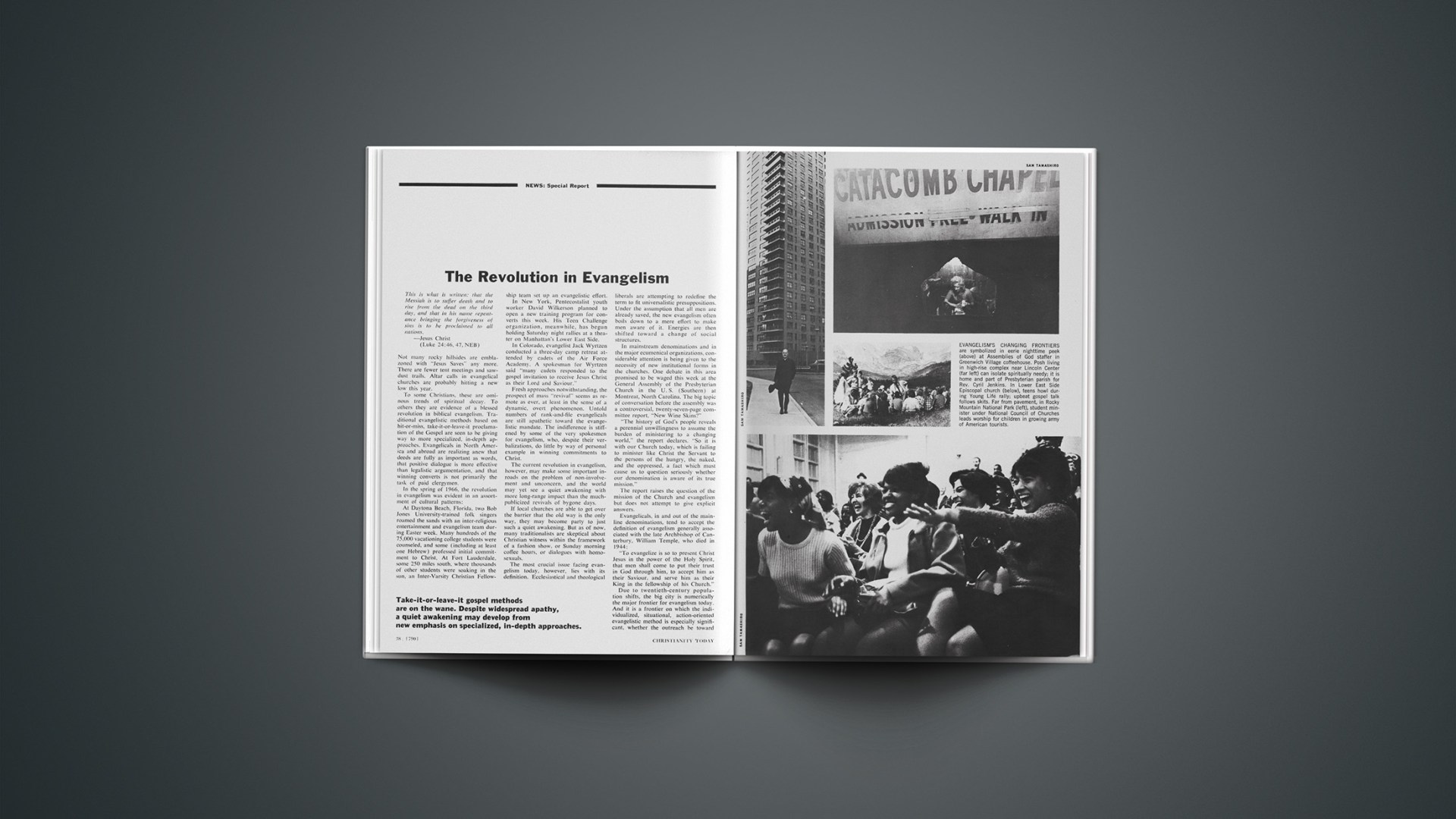

Due to twentieth-century population shifts, the big city is numerically the major frontier for evangelism today. And it is a frontier on which the individualized, situational, action-oriented evangelistic method is especially significant, whether the outreach be toward the poverty-stricken, neglected slum-dweller or toward the affluent sophisticate who seeks seclusion in high-rise apartments.

“Our evangelism is one-to-one, and in depth,” says 25-year-old Bill Milliken, congenial, hard-working director of the Youth Life Crusade’s Lower East Side branch in Manhattan. Among churches cooperating with Young Life and Harlem’s influential Church of the Master and the Church of the Sea and Land, a few blocks from the tenements where Young Life offers housing to homeless youths who are interested in Christianity.

In Philadelphia, the American Sunday School Union, which for 149 years has been working in the now nearly forgotten area of rural evangelism, is expanding a relatively new urban program and hopes to launch similar efforts in other major cities. Work in rural areas, where some 1,500 Sunday schools are currently being maintained, will continue.

Apartment-dwellers are probably the biggest challenge to the evangelistic outreach of the church today. A survey made in the Washington, D. C., area, last year showed that fewer than 5 per cent of apartment-dwellers belong to any church. Many apartment buildings, especially those of the luxury type, are sealed against visitation programs by locks and guards. The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod tried to meet the challenge by assigning a minister to live in Chicago’s plush Marina City. Says the Rev. Roy Blumhorst, who lives with his wife and three children in a forty-seventh-floor efficiency:

“I agree with locking the salesman out, and locking out the clergyman who would be a door-to-door salesman. If somebody is going to have a brush with Christianity, it should be in the person of a Christian layman who is interested in him, his neighbor or co-worker.”

This principle of Christian witness is the subject of a film produced by the National Association of Evangelicals. Without disparaging institutional church structures, the film points to the great need for every Christian to be a living witness in his own situation.

Such person-to-person confrontation is the object of the non-church International Christian Leadership groups, famous for their prayer breakfasts in which persons well known in government and business are exposed to soft-sell evangelism. These breakfasts, along with ICL-sponsored Bible studies in homes and offices, have spread across all of North America and to major world capitals.

But what will happen to the more traditional forms of evangelism? Many are still valid but are becoming more specialized and intensified. A prime example is the evangelism-in-depth concept developed by Latin America Mission. Large public rallies resemble evangelistic meetings of long ago, but preparation and follow-up on a vast scale have been added.

Even that lowly symbol of evangelicalism, the gospel tract, is getting new treatment. More and more tracts are aimed at particular audiences and situations. An example is that put out every four years by Washington Bible College for Presidential inaugurations, with interesting historical data supplemented by a spiritual message. Last Inaguration Day WBC students distributed 110,000 copies.

The basic way of evangelizing, giving out Scripture portions, is a bigger enterprise than ever and is undergoing some updating of its own. The American Bible Society now distributes Scriptures in assorted translations—some illustrated—with attractive bindings. The society opened a series of 150th-anniversary ceremonies this month with the dedication of a new twelve-story Bible House along Broadway. President Johnson recently was presented with a special commemorative Bible representing the 750 millionth copy of Scripture distributed by the society.

With little doubt, the most crucial frontier in evangelism today is youth work. And here evangelist Billy Graham is becoming increasingly effective. Whether by design or not, Graham’s mass-evangelism techniques are arresting teen-agers far more than any other age group. This month, the evangelist is preparing for what he says will be his best-organized, most intensive crusade yet, a thirty-two-day effort in London beginning June 1.1Decision magazine reports there is a “distinct posibility” that Graham and his team will hold four meetings in Warsaw, Poland, in September of 1967, at the invitation of evangelical churches in that country. Other 1967 meetings are scheduled across Canada and in Puerto Rico, Tokyo, and Kansas City, Missouri. Graham has also been invited to conduct a summer crusade in 1968 in the new Madison Square Garden being built in New York.

Later this year, as a prelude to the World Congress on Evangelism, Graham will be holding a crusade in Berlin. He will also be a featured speaker at the congress, of which he is honorary chairman. The congress, scheduled for October 26-November 4, will climax years of praying and planning for an event to summon the churches to the fulfillment of their spiritual priorities. It is a tenth-anniversary project of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, with the aim of facing the duty and need of evangelism, the obstacles and opportunities, the resources and rewards, and encouraging Christian believers in a mighty offensive for the Gospel in the remaining third of the twentieth century.

Salvation In Saigon

An opening night crowd of more than 6,000 on April 2 witnessed the start of a ten-day preaching crusade in Saigon, South Viet Nam, believed to be the first of its kind. Although the campaign took a back seat to political turmoil (see story, page 44), the contrast with the riots and near-riots could not have gone unnoticed by military rulers who were the brunt of Buddhist agitation. On opening day, evangelists and church leaders met with Chief of State Nguyen Van Thieu at Gio Long Palace. The meeting was cordial and Thieu, a Roman Catholic, expressed the nation’s thanks for the visitors and their purpose.

The all-Asian team was led by the Rev. Gregorio Tingson of the Philippines, chairman of Asian Evangelists Commission, founded in 1964 with the aim of “Asians Winning Asians for Christ.”

Communists were interested, since the word “campaign” in Vietnamese has both military and political connotations. A Red cadre met a local pastor to ask what was going on, and was assured the meetings had no political purpose.

When a 9 P.M. curfew was clamped on the city, meetings were held earlier. This, and limiting of U. S. soldiers to quarters, kept attendance down. Many who went had to make long detours to avoid the widespread street demonstrations; some were accused of being demonstrators, others went home weeping because of lingering tear gas.

At week’s end, some 700 decisions for Christ had been made at Cong Hoa Olympic Stadium, which seats 20,000. Meetings were extended for another week at the large Saigon Protestant Vietnamese Church.

Many poor Christians across the country who had lost everything in last year’s flood or through war devastation gave amazing amounts to back the Saigon crusade. Before it opened, the goal of 700,000 piasters ($10,000) had been far surpassed.

Spiritual forces in the war-torn land were also shored up last month at a retreat in Dalat that drew 400 delegates, nearly every native pastor and missionary in the country. The session did much to create understanding between Vietnamese and foreigners. Many came to Dalat from Red-held areas.

A ‘Future’ In Their Future

Roman Catholic conservatives are about to get their own magazine—by June if the founders can get body and soul together by then. The fortnightly thought journal, with headquarters a few blocks from the White House, is called Future.

The editor is red-haired lawyer L. Brent Bozell, 39, who has been associated with another prominent Roman Catholic, William F. Buckley, Jr., on the slick right-wing political journal National Review.

“Why another magazine?” asks an editorial in a thirty-four page mock-up edition. The answer, essentially, is that the church is in trouble, and “existing Catholic journals of opinions are increasingly a monolith harnessed to the assumptions of liberal ideology.… Our immediate task is to fill a void, to right a scandal, to make sure that at least one journal of opinion in a nation of 45 million Catholics is open to the traditional voice of the Christian Church.”

Bozell, who has the accent and blunt elegance of his fellow ex-Yalie Buckley, asserts that “no Catholic journal outside the scholarly publications is intellectually impressive.” That includes Commonweal, for instance, and he says America makes no “pretensions” to scholarship. He thinks the Catholic who wants to know what’s really going on can do no better than the National Catholic Reporter, but “in many ways, it is a scandal sheet.”

Future will be edited by laymen but will seek advice and contributions from clergymen. And while “we will have political commentary, this is emphatically secondary,” Bozell says.

The issues of interest to Future can be sensed in quotes from advance publicity: “We will have much to say about the scandal of a third of the Church suffering Christ’s Cross behind the Iron Curtain … we shall be urging policies looking toward its liberation.… Our editorials will be concerned with the alarming drop of conversions in this country in recent years.”

Future contends that “spiritual exhaustion” is parading under the banner of ecumenism, and that the culture is in danger of “total secularization.” It is “tired of attacks on the Catholic school system, that marvel of the modern Church.”

Bozell shuns comparison with Father Gommar DePauw’s Catholic Traditionalist Movement, saying that DePauw is too narrow in focusing on liturgy and that “it is imprudent for such reaction to be spearheaded by a priest.”

The editor says there is nothing wrong with the sort of cooperation with Protestants that existed before Vatican II, “but I am very much alarmed by the current tendency to pretend doctrine is insignificant. We are serious about our Catholicism, and we expect others to be serious about their beliefs.”

On the church-state question, Future will favor the nineteenth-century doctrine stated by Bozell as follows: “Where Roman Catholics form a large percentage of the population, it is right and proper to represent officially the nation’s religious commitment. Only where there is marked pluralism should civil authorities remain neutral.”

The new magazine will have twenty-eight to thirty-two pages with slick paper and an urbane appearance. Some articles by writers opposed to the editorial policies, including Protestants, will be published. Those who work on other religious publications will be surprised to learn that Bozell thinks his magazine can pay its own way through advertising and subscription income.

Poor Showing

Dr. Eugene Carson Blake, general secretary-elect of the World Council of Churches, closed a Citizens’ Crusade Against Poverty convention in Washington, D. C., April 14 when things got out of hand. As leaders of 100 organizations, including many churchmen, worked on resolutions urging more participation of the poor in the federal war on poverty, unruly poverty victims took over the meeting and hurled complaints and insults.

Poverty war director Sargent Shriver quit the meeting commenting. “I will not participate in a riot.” Blake, crusade vice-chairman, told the crowd, “There won’t be anything left to take over when you take over.” But he and other leaders said after the debacle that frustrations of poor people are understandable and the crusade will continue.

Death Of God Again

New fuel for the death-of-God debate is being fed into bookstores this spring. From Bobbs Merrill comes a 202-page paperback, Radical Theology and the Death of God, containing a series of essays by Drs. Thomas J. J. Altizer and William Hamilton, and from Westminster Press comes a 157-page paperback that is the product of Altizer alone.

Altizer et al. were treated to big play in major pre-Easter articles in Look, Time, and Newsweek, and in an infinite number of Easter sermons, pro and con. Now attention shifts again to the bookshelf. Dr. Robert McAfee Brown opens the debate with a blurb on the cover of the Westminster book, entitled The Gospel of Christian Atheism. Says Brown, “It is not a gospel …; it is not Christian …; and it is not atheism.… In an attempt to celebrate the ‘death of God,’ this book succeeds only in demonstrating the death of the ‘death-of-God theology.’ ”