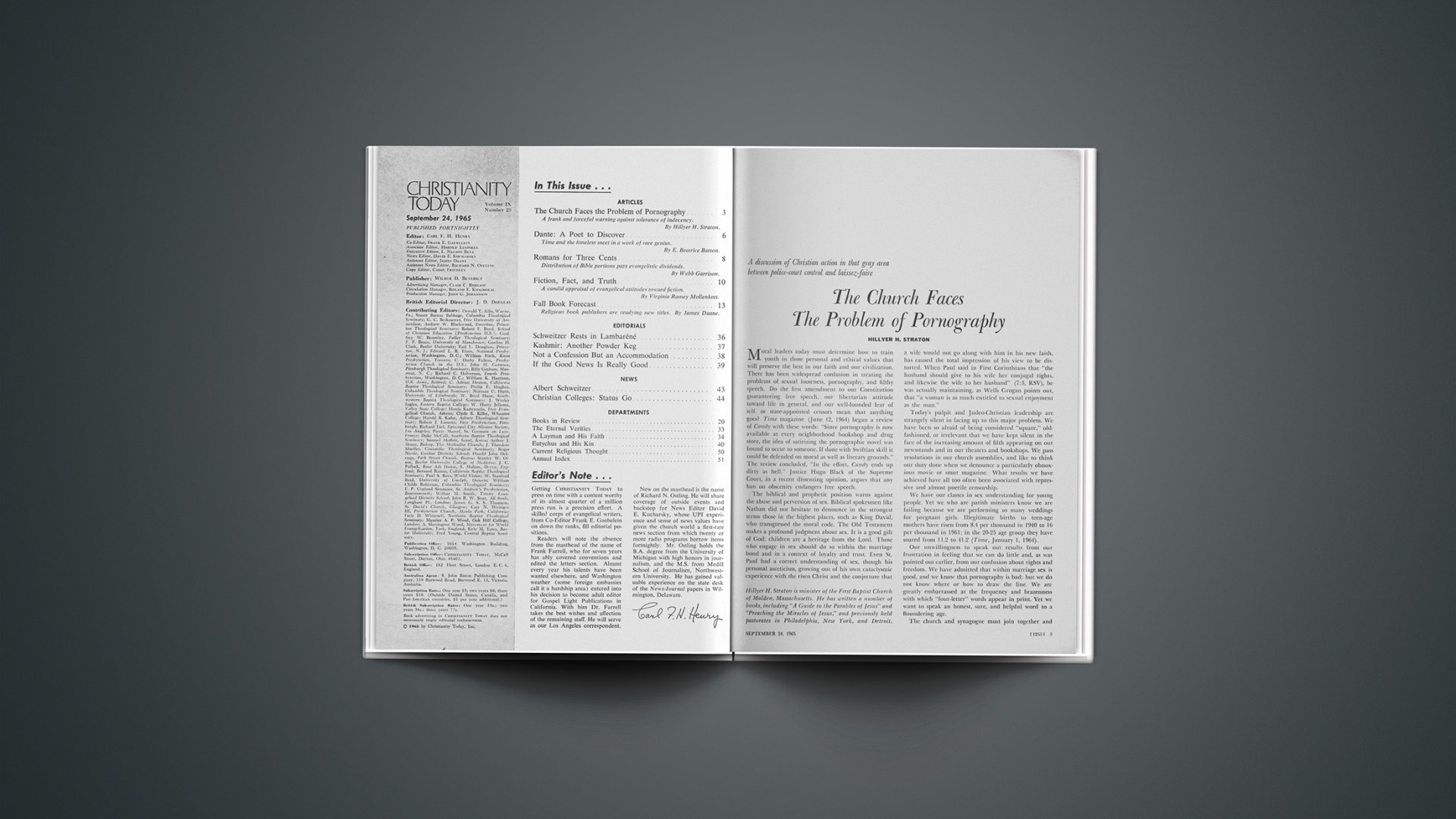

A discussion of Christian action in that gray area between police-court control and laissez-faire

Moral leaders today must determine how to train youth in those personal and ethical values that will preserve the best in our faith and our civilization. There has been widespread confusion in treating the problems of sexual looseness, pornography, and filthy speech. Do the first amendment to our Constitution guaranteeing free speech, our libertarian attitude toward life in general, and our well-founded fear of self- or state-appointed censors mean that anything goes? Time magazine (June 12, 1964) began a review of Candy with these words: “Since pornography is now available at every neighborhood bookshop and drug store, the idea of satirizing the pornographic novel was bound to occur to someone. If done with Swiftian skill it could be defended on moral as well as literary grounds.” The review concluded, “In the effort, Candy ends up dirty as hell.” Justice Hugo Black of the Supreme Court, in a recent dissenting opinion, argues that any ban on obscenity endangers free speech.

The biblical and prophetic position warns against the abuse and perversion of sex. Biblical spokesmen like Nathan did not hesitate to denounce in the strongest terms those in the highest places, such as King David, who transgressed the moral code. The Old Testament makes a profound judgment about sex. It is a good gift of God; children are a heritage from the Lord. Those who engage in sex should do so within the marriage bond and in a context of loyalty and trust. Even St. Paul had a correct understanding of sex, though his personal asceticism, growing out of his own cataclysmic experience with the risen Christ and the conjecture that a wife would not go along with him in his new faith, has caused the total impression of his view to be distorted. When Paul said in First Corinthians that “the husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband” (7:3, RSV), he was actually maintaining, as Wells Grogan points out, that “a woman is as much entitled to sexual enjoyment as the man.”

Today’s pulpit and Judeo-Christian leadership are strangely silent in facing up to this major problem. We have been so afraid of being considered “square,” old-fashioned, or irrelevant that we have kept silent in the face of the increasing amount of filth appearing on our newsstands and in our theaters and bookshops. We pass resolutions in our church assemblies, and like to think our duty done when we denounce a particularly obnoxious movie or smut magazine. What results we have achieved have all too often been associated with repressive and almost puerile censorship.

We have our classes in sex understanding for young people. Yet we who are parish ministers know we are failing because we are performing so many weddings for pregnant girls. Illegitimate births to teen-age mothers have risen from 8.4 per thousand in 1940 to 16 per thousand in 1961; in the 20–25 age group they have soared from 11.2 to 41.2 (Time, January 1, 1964).

Our unwillingness to speak out results from our frustration in feeling that we can do little and, as was pointed out earlier, from our confusion about rights and freedom. We have admitted that within marriage sex is good, and we know that pornography is bad; but we do not know where or how to draw the line. We are greatly embarrassed at the frequency and brazenness with which “four-letter” words appear in print. Yet we want to speak an honest, sure, and helpful word to a floundering age.

The church and synagogue must join together and let their voice again be heard. Forty years ago people as diverse theologically as John Roach Straton, John Haynes Holmes, and Stephen Wise were speaking to the nation on the moral breakdown in their day. Then people at least knew where major religious leaders stood. For too long now we have abdicated our responsibility to proclaim what we believe to be the right standards, allowing the academic, artistic, and judicial worlds to give what they think is the answer. And too often their position is one of laissez-faire, or at most of ridicule.

Yet the world of religion does have something to say. We have been puritanical, we have made mistakes, and we have been narrow when we should have been understanding; but at our best we have said with Jesus, “Neither do I condemn thee; go and sin no more.” The centuries have proved us more right than wrong. We can join forces with any who will help us—academic, artistic, judicial, civic groups—but speak out we must. The homes of a nation are at stake, and wise homemakers will be our allies. If we do not find a solution, we might be overcome by the sexual anarchy that engulfed Greece in the third and second centuries B.C. According to Pitirim Sorokin, Harvard sociologist, “there were men in those days who prided themselves on their objectivity as they calmly recorded the distressing picture of whole families getting together to indulge themselves in promiscuous behaviour. Adultery, prostitution, homosexuality, and even incest were so common that those who indulged were regarded merely as interesting fellows” (Time, January 11, 1954).

Take for instance the matter of filthy speech. According to news reports, there is actually a far-left group hanging around the University of California at Berkeley that has as its reason for being the use of obscene language. The anarchistic spirit that motivates such people is obvious. Having gone to sea as a wireless operator, served a stint in the Army, and taken part in many college bull sessions, I probably know all the dirty words there are; and I fail to see any point in using them. Our generation has rightly put a premium on forthrightness as a kind of revolt against Victorian prudery. But the large question of good taste enters here.

One of the ugliest words to be found in the English language is “snot,” which, though it has nothing to do with sex, is avoided in decent homes. In medical circles euphemisms have their place and spare from embarrassment the man of science, the lay person, and the child. “Bowel movement” is a perfectly acceptable expression for the much more direct but offensive four-letter word. Everyone knows the earthy word for copulation, but even breeders do not use it in their business. Certainly true lovers never would. I doubt whether even those who engage in sexual relations outside of wedlock use such a word, if they care at all for each other.

There is a certain fitness in things that makes it unseemly. A case in point is the review by John Phillips, published in the New York Review of Books, of the biography of General George Patton, and its use of a barrack-room term as being “relevant” even if shocking. I can grant its relevance in the barrack room, but I wonder whether Patton himself would have stood for it in his headquarters, even from an equal in rank. No amount of “relevance” would make it good usage for a mixed class, public platform, or church gathering. There are some expressions gentlemen just do not use in public. Prudery has nothing to do with it.

The Church and its leaders have made it abundantly clear that they believe sex is wise and right, as is proclaimed at every marriage ceremony. But parading of details of sex can be pornographic, especially when they are used to exploit a prurient interest, or for financial gain. To help in my pastoral counseling, some years ago I purchased Van der Velde’s Ideal Marriage, which is the definitive work on the subject. My name got on a mailing list. Ever since then I have been bombarded by announcements of various new or different books—always exorbitantly priced—on various aspects of sex, with the prurient interest obvious in the advertising blurbs.

In a discerning article in the March, 1965, issue of Harper’s Magazine, George P. Elliott defines pornography as “the representation of directly or indirectly erotic acts with an intrusive vividness which offends decency without aesthetic justification.” There are points at which I take issue with Elliott, but he does make a telling case for the idea that much of today’s pornography is of importance to the body politic because “it is used as a seat of operations by erotic nihilists who would like to destroy every sort of social and moral law. Pornography is one of their weapons.” One of the main cases to be made against pornography is that it is an insult to sex, a prostitution, a debasing of what is noble. To twist that which is given for the highest purpose of propagating the race (the biblical phrase is “be fruitful and multiply”), and of keeping the home together, is evil. It has been pointed out that a good share of the humor in today’s novels and plays is based on homosexuality. The most charitable find it difficult to find any social values here other than personal release.

Several years ago the Saturday Review carried an account of a conference between prominent American and Russian citizens at which one of the Russians asked some pertinent questions:

Why do your playwrights and authors insist on slandering your great country? Almost every motion picture we see about the United States does serious discredit and harm to your people. You are made to seem very vulgar and materialistic, as though you had no interest in the deeper things of life, which I know is not true.… I read as many books about America as I can find. They are far more responsible, of course, than your movies, but I still think the writers of these books do not do justice to your country and its people. Your writers make it appear that the United States is filled with people who are neurotic or over-sexed or who suffer from infantile emotions.… I saw an open-air store—I think you call it a newsstand. There seemed to be hundreds of magazines on display. Please do not think me critical, but most of these magazines were outrageously indecent. It creates the impression that the only things the American people are interested in are violence, drunkenness, and cheap women. It didn’t take me long to find out that this is not the case. But I still don’t understand why so much of your printed material, like your movies, should glorify the worst things about America and not your best [Saturday Review, December 15, 1962, p. 15].

It is a tragedy that those in the movie industry seem to feel that true expression can come only where taste is debased. Ingmar Bergman is unquestionably an artist. Yet the Church should say loudly that a film does not have to take people through sewers to be artistic. Sewers are necessary, but they are not the place for a family outing. Bergman said of his far-out scenes (at least one of which, I am told, goes to the length of depicting copulation):

Of course we have to educate the audience. It is our duty. At first you give the audience a pill that tastes good. And then you give them some more pills with vitamins, but with some poison, too. Very slowly you give them stronger and stronger doses [Time, November 11, 1963].

True art can express the whole gamut of human emotions without resorting to pornography. There is not a pornographic line in Anna Karenina; yet the basis of the plot of this masterpiece by Tolstoi is an illicit relation.

Let no one say that the Church does not have its prophets, its fearless spokesmen against the evils of our day. We have taken a forthright position on the question of racial justice. Men of good will are marching together to win human dignity for the Negro and to preserve it for all races. We are speaking out on the question of war and disarmament. We are concerning ourselves about poverty and decent housing. To deny our responsibility to speak to the pornography issue by saying, as one New York divine did, that “the bomb” is a greater obscenity, is to cloud the issue. (Of course the bomb is an “obscenity,” if one wishes to use that term, which raises a question of semantics.) It is frighteningly true that a civilization can be, and historically has been, destroyed as surely by sexual looseness as by the bomb.

The Church does have something to say and do in this struggle. First, let us continue to proclaim that sex is good and the marriage bed undefiled; and let us also proclaim chastity as a virtue—on the biblical ground of one man for one woman and, as a concession to a troubled age, on the weaker ground of prudence. Secondly, let us proclaim that censorship is out. It has smacked too much of police-court control and of blue lawyers who understand little of human nature. Thirdly, because of the close relation of the Church to the home as well as in its own right, let us feel obligated to preserve good taste. Fourthly, let us welcome every aid from critics whose judgment about the tawdriness of so much that claims to be “art” is above suspicion. Finally, let us join forces with right-minded citizens in seeing that infection is stopped at the source. The French finally did it in driving the Olympia Press out of business. It seems that certain publishers in the United States are interested, not in freedom of speech, but in exorbitant profits at the expense of the youth and the unstable of the land. In the article referred to above, George Elliott comes out for an intelligent “censorship.” The word carries so many connotations of unhappy and unwise repression that it should be avoided. However a wise and a fundamentally good people need not feel that they are helpless.

Why cannot concerned citizens sponsor a control board on a national level? It would be composed of a small group of top-flight persons from the artistic world, sociologists, jurists, educators, and clergymen, as well as some with wide experience and stature in the political field. Such a board would seek out the best ways of attaining the goal of an uncorrupted public. Its prestige would mean that it would rarely have to resort to legal action. Of course, any such board would be opposed as vigorously as are the advocates of laws against the indiscriminate sale of firearms by mail-order houses; but this should not deter us. The life of a President was forfeited because of the short-sighted, archaic view that a free man ought to be able to buy firearms just as he pleases. It has been said again and again, but it still is true, that freedom of speech does not give me the right to shout “Fire” in a crowded auditorium.

On two visits to Pompeii I saw an example of what can be done. In 1952 my companion and I were beseigecl by at least a dozen young men wanting to sell us “feelthy” pictures, photographs of scenes taken from brothels in ancient Pompeii. In 1964 they were no longer for sale. Some authoritative power had said, “This is not good for Italy or for the tourist trade.” My freedom was not infringed. If as a sociologist I had wanted to obtain such pictures, I could have arranged to do so. But the tourists visiting that fascinating area are now neither offended nor corrupted by other peoples’ lack of taste.

To sum up: The Church and its leaders ought to be clear about what it is for and what it is against. It is for sex between married partners. It is against pornography as an insult to sex and a debilitating factor in the body politic. It is against filthy speech as a matter of good taste. It should insist in these areas that its voice be heard along with those of the artistic, judicial, and educational worlds. It should join men of good will in working out a plan to continue the undergirding of freedoms while denying to a very small minority the opportunity to make great profit from the debauching of our youth.

What is the power of this masterpiece that forced one reader to forsake food, sleep, work, and correspondence?

This year marks the seven-hundredth anniversary of the birth of the great Italian poet, Dante Alighieri. His complex allegory, The Divine Comedy, is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of the literature of the Western world. Scores of persons are exposed to this great work year after year. Some stand in awe of the many levels of meaning and want to probe more deeply; others admit that there must be something great about the poem but are sure that its greatness must lie in its encyclopedic view of an age centuries removed from their own; and others declare that it is a work some have called great, but that they are not sure why.

No one would want to suggest that the Divine Comedy is easy to unlock. Dante himself found that the conception and writing of the work required an almost superhuman effort; but he wished his poem to be difficult. Perhaps he held what too many have forgotten: there is no easy route to excellence. But, as in any other undertaking, the only way to move forward in the one hundred cantos of the Divine Comedy is to begin.

Many who have come to enjoy Dante’s work thoroughly tell of their slow start and halting questionings at the beginning. The distinguished Columbia professor Gilbert Highet, who was brought up as a Presbyterian in Scotland, tells that he was given to believe that the Divine Comedy was a grim Roman Catholic book full of gloatings over the sufferings of heretics (such as his parents, his friends, and himself) and compressed within the intellectual system of the Middle Ages. Consequently, he did not read the poem until he was over thirty years of age. In fact, he says that he never thought of reading Dante seriously until he was virtually compelled to do so, adding parenthetically, “Much of the best education we get comes to us through compulsion; for it is not always true that ‘we needs must love the highest when we see it’ ” (“An Introduction to Dante,” p. 5).

Professor Highet first read the Divine Comedy in preparation for teaching the work in a humanities course. He frankly admits that he did not teach Dante well the first year; but by the following year the poem had been living in his mind, and he looked forward to rereading it and showing its beauties to his students. As his experience with Dante continued to grow and deepen, he could say, “I could read it all through with no reluctance, but rather with the same amazement as a visitor feels when he walks through a Gothic church full of symbols and decorations and sanctities and mysteries” (“An Introduction to Dante,” p. 8). After numerous rereadings, both in various translations and in the poet’s own language, he came to feel at home in the newly discovered world of Dante.

Another great lover of the Divine Comedy, Dorothy Sayers, who later became a translator and scholar of the work, discovered Dante late in life. When she was reading a work by Charles Williams entitled The Figure of Beatrice (not because it was about Dante, but because it was written by Charles Williams), she began to believe that the world had been right in calling Dante a great poet. Some time after that, she dusted off the three volumes of the Temple Divine Comedy which had originally belonged, she thought, to her grandmother. She began to read Canto I, “resolute, but inwardly convinced” that she would perhaps “read ten cantos with conscious and self-conscious interest, and then—in the way these things happen—one day forget to go on.” But instead, her reaction, as she later described it, was this:

However foolish it may sound, the plain fact is that I bolted my meals, neglected my sleep, work, and correspondence, drove my friends crazy … until I had panted my way through the three Realms of the Dead from top to bottom and from bottom to top; and that, having finished, I found the rest of the world’s literature so lacking in pep and incident that I pushed it all peevishly aside and started out from the Dark Wood all over again [Further Papers on Dante, p. 2].

But these two discoveries were made by persons who work in the field of literature as an academic discipline. Consider one further discovery. The well-known theologian Augustus Strong tells of a summer vacation which he and “a little company of fairly intelligent people” with him determined to put to use. Someone spoke of the Divine Comedy and wondered whether anybody among them had ever read it from beginning to end. None had, but several had read the “Inferno” and had to admit that after finishing the first lap of the journey, they really had not cared to go further.

On this vacation, a new resolve was taken. They would begin and finish Dante’s great work. Setting aside an hour and a half each morning, the vacationers completed their task. The distinguished theologian described the experience in this way: “Indeed, it was no task; the pauses for discussion were numberless; its beauty grew upon us; when we finally closed our books, the four weeks seemed four days for the love we bore the poet and the poem” (The Great Poets and Their Theology, p. 108).

Such expressions of exhilaration on the part of those who have discovered Dante do not necessarily show what his masterpiece is all about or why it grips the human mind. Where does one begin if he, too, wants to discover Dante?

In a letter that tradition assigns to Dante, addressed to his patron, Can Grande della Scala, the poet himself gives suggestions for a beginning point. He explicitly states, “… if the work is understood in its allegorical intention, the subject of it is man, of his free will, he is justly opened to rewards and punishments.” That letter may be a forgery, as some scholars insist, but it is implicitly obvious in the poem that Dante sets forth man, free to obey or disobey God but morally responsible for the choices he makes. Dante never excuses any person with the scores of “cheap” reasons known to contemporary man.

Dante declares in the same letter that his poem, with man as its subject, has at least four levels of meaning: narrative or literal, moral, allegorical, and anagogical. This could be one method through which the reader could study the subject of man throughout the various realms of the poem.

Ferreting out the multiple meanings of the elaborate allegory would be an endless task, but as one moves downward through the various circles of the Inferno, upward through the terraces of Purgatorio, and further around the sphere of Paradiso, he soon discovers that there is one unifying theme: man’s lost condition and his need for restoration. The multiple meanings converge in one central meaning as the poet envisions man in his journey from the lostness of a “dark wood” into the presence of a majestic God.

Dante tells us where and when he started the journey:

Midway this way of life we’re bound upon

I woke to find myself in a dark wood

Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.

Finding himself on the wrong road, the poet sees the light glowing atop a high hill. He then races up the slope to what would be immediate salvation if he could manage to reach that light. He knows he is in darkness and he wants the light; but deliverance is not obtained by racing up the hill to the light. Dante finds his way blocked by three beasts, each representative of sin which prevents man from reaching salvation. There is a She-wolf that represents the sins of Incontinence or the sins of self-indulgence, a Lion that represents the sins of Violence or the bestial sins, and a Leopard that represents Fraud or the malicious sins. Into these three categories fall all the sins common to mankind, and man must recognize how blinding and destructive sin is before he sees ultimate Light. The three beasts destroy Dante’s hope of continuing his ascent up the steep hill by blocking his way and driving him back into the darkness.

In that darkness there appears someone to tell Dante that there is no such easy road to light as he is attempting. “He must go by another way who would escape this wilderness,” says Dante’s new guide, Virgil (representative of the summation of human wisdom). And this “other way” is the long journey through the grim darkness of the Inferno, into the breaking light of the Purgatorio, and finally up to the climactic vision of God in the Paradiso. This is the route of the Divine Comedy. “It is,” as one student of Dante, the poet and critic John Ciardi, says, “the painful descent into Hell—to the recognition of sin. It is the difficult ascent of Purgatory—to the renunciation of sin. Then only may Dante begin the soaring flight into Paradise, guided now by Beatrice [representative of Divine Revelation or Infinite Love], to the rapturous presence of God” (“How to Read Dante,” Saturday Review, June 13, 1961). At the intercession of St. Bernard, Dante is enabled to gaze directly upon God; he is so moved that he prays grace may be given him to speak what he sees, that generations “yet unborn” may catch some glimpse of the sublime vision.

Some Protestant readers of the Divine Comedy are quick to point up their disagreement with Dante’s “way” to God. Certain aspects of his thinking are decidedly in the tradition of the Roman faith, but only the most petulant will overlook the basically Christian vision that underlies the poem. Surely none can forget the tremendous passages (as, for example, Canto VII of “Paradiso”) which reveal so clearly that man’s redemption from his guilt and sin is through the substitutionary work of Christ. Canto VII has sometimes been called “the finest poetic expression of Atonement theology ever written.” All readers may well keep in mind this cautious suggestion made by John Ciardi:

Dante expresses his arduous and ardent vision of Catholicism in the most monumental metaphoric structure to be found in all European Literature.… But Catholicism is no more a prerequisite to the reading than a belief in the gods of Olympus is a prerequisite to the reading of Homer [“700 Years After: The Relevance of Dante,” Saturday Review, May 15, 1965].

To this statement should be added a further word of counsel from Ciardi: “The Catholic reader who takes Dante literally, accepting the poetic details as stated creed rather than as metaphors, would, in fact, be confusing his own doctrine in the act of misunderstanding the poem.” The point is that the Divine Comedy is a poem—not a literary analogue of Thomas Aquinas’s Summa, as some would suggest. Undoubtedly the Thomistic synthesis captured Dante’s imagination and made it possible for him to set forth in the Divine Comedy a great, orderly view of the universe. To both Dante and Aquinas, the universe made sense; it had order. But if the reader fails to see Dante’s metaphoric structure, not as rhymed Aquinas theology, or as a synthesis of medieval European thought, but as what Ciardi calls “vast metaphoric perceptions of the human condition,” he misses the poem.

The Divine Comedy is an exciting artistic fusion of time and the timeless. Its author is preoccupied with man’s condition in relation to God. The poem is an allegory of the way to God, in which the finite will bows and stands in adoration of the Infinite will. Having made this discovery, the reader realizes that the numerous images of the vast poem continue to yield and that it is impossible to penetrate fully to the heart of the masterpiece. But as Gilbert Highet wisely cautioned in the work referred to earlier, “They [masterpieces] are too rich … to compass them fully.… They exist not so that we may swallow them down in a single gulp, but so that we can gradually learn from them, and use them to help ourselves to grow a little closer to their greatness.” And the growth does not start until we begin to discover.

T. Leo Brannon is pastor of the First Methodist Church of Samson, Alabama. He received the B.S. degree from Troy State College and the B.D. from Emory University.