“The people of Selma will struggle for the soul of the nation,” said Dr. Martin Luther King, “but it is fitting that all Americans help to bear the burden. I call, therefore, on clergy of all faiths, representative of every part of the country, to join me in Selma for a ministers’ march on Montgomery.”

Not even the Vatican could have elicited a more prompt and enthusiastic response. Within twenty-four hours hundreds of ministers, priests, rabbis, and even nuns in many states were preparing to leave for Selma or already on their way. For at least one clergyman it meant death.

Said the Rev. Bruce Hansen of the National Council of Churches’ Commission on Religion and Race: “We’re not sure that Dr. King’s appeal triggered response as much as photographs in newspapers and on television showing Negroes being clubbed.”

Hansen was referring to the outrageous event of Sunday, March 7, when club-swinging Alabama state troopers and local deputies fired tear gas and charged a group of Negroes engaged in a march in behalf of their right to vote. A crowd of white bystanders cheered the action.

Whatever the motivation, the response of the American clergy was remarkable. It illustrated the fact that not since the days immediately prior to prohibition has a single issue so preoccupied the men of the cloth as has the civil rights movement. The logical liberals who usually shun emotional religious experience found themselves locked arm in arm with their Negro brethren, swinging and singing, “We Shall Overcome.” Thousands of clergymen who did not venture to Selma thrust aside prepared sermons in favor of impassioned pleas for racial equality.

For many clergymen, involvement in the crisis in Selma extended the deepening controversy over the propriety of a minister’s demonstrative intrusion into a social struggle, even when there are moral considerations. Many still question the advisability of a minister’s projecting himself into alien situations in parts of the country with which he is unfamiliar. Others worry about the unity of their own congregations and about the impact of a strong stand upon their own wives and families.

Some ask how leading churchmen can be so vocal for civil rights and yet so squeamish about invoking church discipline against flagrant violators. The Methodist Board of Christian Social Concerns champions the cause of the right of every American to vote. Yet Governor George Wallace of Alabama is able to remain a Methodist in good standing despite his implicit repudiation of the voting principle.

The situation in Selma called nonetheless for some sort of action by the American Christian establishment. For all the inconsistencies and fantastic proof-texting1Like referring to King’s appeal as a “Macedonian call” (Acts 16:9) and citing demonstrators as presenting their bodies “a living sacrifice” (Rom. 12:1). of the clergy marchers, they offered a striking contrast to the host of evangelicals in America who remained silent. Evangelical churchmen almost universally deplored the brutality of Alabama police and shared sympathy for the Negro demand for full voting privileges, but many hesitated to identify themselves with clergy social-action pressures. They were not particularly impressed with the reliance on techniques of mob pressure rather than on judicial process. They shared concern about the growing weight of ecclesiastical example on the side of civil disobedience.

It would have been much better, some churchmen contended, had Alabama clergymen themselves stepped into the vacuum on a larger scale, and better still if lay churchmen rather than clergy had taken up the cause en masse.

Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, who on the eve of the Selma flareup was elected president of the Protestant Council of the City of New York, was obliged to take an immediate stand. He had been the target of a petition that criticized his candidacy, charging, among other things, that he has been too silent on the racial issue. As if in rebuttal to the charge, Peale was quoted in telegrams to President Johnson and Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach as calling upon the Chief Executive to take “appropriate action” to protect Negro demonstrators. A news release issued by the Protestant Council said that Peale also asked two council officials to go to Selma to support the cause of racial justice.

Clergymen in the Washington, D. C., area sought to set the pace by chartering an airliner the day after King’s appeal. Forty persons got on board, and a number of others were reportedly turned away. Some proceeded south via commercial flights.

Dr. George M. Docherty, minister of the historic New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in the nation’s capital, accused President Johnson of “straddling the fence” by avoiding federal intervention. “The one man who could have solved this problem remained in Washington,” said the Glasgow-born minister, now a naturalized American citizen. “He should have been at the head of the line of marchers, symbolizing by his presence his protest against an iniquitous, fascist system for which there is no place in the American Constitution.”

Other Washington clergymen turned their attention toward the Capitol and began using their influence upon Congress to pass a new voting bill. Dean Francis B. Sayre of Washington Cathedral and two of his priests went to the offices of Democratic Senator John Sparkman of Alabama and other congressmen to state their positions.

The National Council of Churches held a hurriedly arranged mass meeting of clergymen in Washington to dramatize the need for additional voting-rights legislation. An overflow crowd of more than 2,000 gathered at the Lutheran Church of the Reformation on Capitol Hill. A delegation of clergy leaders was dispatched to the White House to meet with President Johnson.

Methodist Bishop John Wesley Lord, United Presbyterian Stated Clerk Dr. Eugene Carson Blake, and President Ben Herbster of the United Church of Christ were among clergymen who conferred with the President. There were also Roman Catholic and Jewish representatives.

Back in Alabama, the demonstrators’ cause see-sawed in the courts. Marchers turned up at numerous points, and Wallace attempted to keep them in check. He seemed determined to shun the visiting clergymen’s protests.

Not all the pressures on Alabama were from out of state. The day before the first march, a group of white Alabama citizens led by a Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod clergyman gathered seventy-strong and walked twelve blocks to the Dallas County courthouse in Selma in support of the Negro voting drive. The Rev. Joseph M. Ellwanger, a white clergyman who leads a Negro congregation, read a statement from the courthouse steps deploring “the totalitarian atmosphere of intimidation.” Before he read the statement, a deputy sheriff stepped in front of him and read a statement from Dr. E. W. Homrighausen, president of the Missouri Synod’s Southern District, which made clear that Ellwanger was acting as an individual clergyman and not as an official representative of the church.

At the Missouri Synod public relations office in New York, it was pointed out that Ellwanger had conferred with Homrighausen in advance of the march. The two reportedly differed as to procedures to be employed in securing voting rights for Negroes but were in agreement as to the objective.

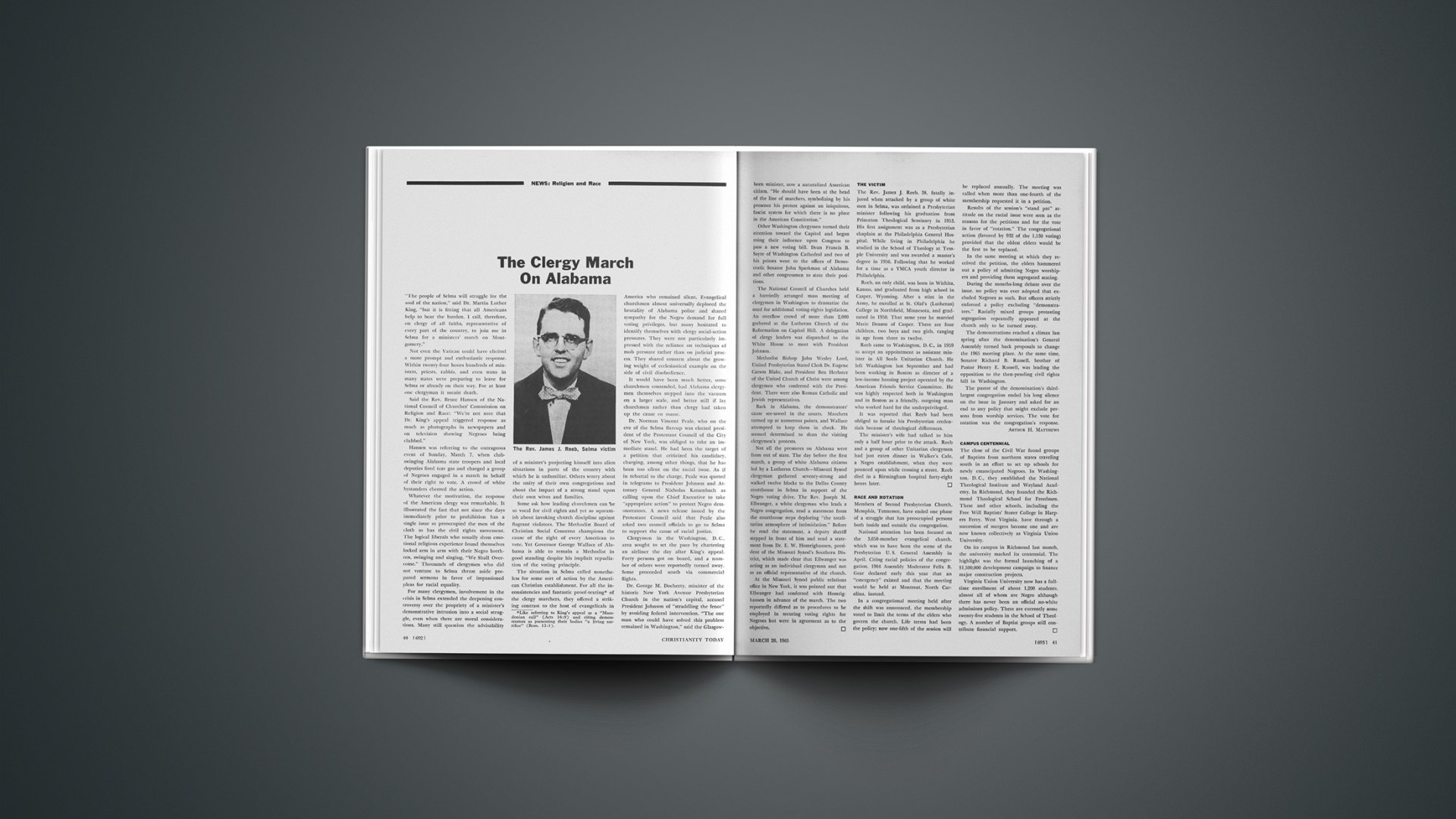

The Victim

The Rev. James J. Reeb, 38, fatally injured when attacked by a group of white men in Selma, was ordained a Presbyterian minister following his graduation from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1953. His first assignment was as a Presbyterian chaplain at the Philadelphia General Hospital. While living in Philadelphia he studied in the School of Theology at Temple University and was awarded a master’s degree in 1956. Following that he worked for a time as a YMCA youth director in Philadelphia.

Reeb, an only child, was born in Wichita, Kansas, and graduated from high school in Casper, Wyoming. After a stint in the Army, he enrolled at St. Olaf’s (Lutheran) College in Northfield, Minnesota, and graduated in 1950. That same year he married Marie Deason of Casper. There are four children, two boys and two girls, ranging in age from three to twelve.

Reeb came to Washington, D. C., in 1959 to accept an appointment as assistant minister in All Souls Unitarian Church. He left Washington last September and had been working in Boston as director of a low-income housing project operated by the American Friends Service Committee. He was highly respected both in Washington and in Boston as a friendly, outgoing man who worked hard for the underprivileged.

It was reported that Reeb had been obliged to forsake his Presbyterian credentials because of theological differences.

The minister’s wife had talked to him only a half hour prior to the attack. Reeb and a group of other Unitarian clergymen had just eaten dinner in Walker’s Cafe, a Negro establishment, when they were pounced upon while crossing a street. Reeb died in a Birmingham hospital forty-eight hours later.

Race And Rotation

Members of Second Presbyterian Church, Memphis, Tennessee, have ended one phase of a struggle that has preoccupied persons both inside and outside the congregation.

National attention has been focused on the 3,650-member evangelical church, which was to have been the scene of the Presbyterian U. S. General Assembly in April. Citing racial policies of the congregation, 1964 Assembly Moderator Felix B. Gear declared early this year that an “emergency” existed and that the meeting would be held at Montreat, North Carolina, instead.

In a congregational meeting held after the shift was announced, the membership voted to limit the terms of the elders who govern the church. Life terms had been the policy; now one-fifth of the session will be replaced annually. The meeting was called when more than one-fourth of the membership requested it in a petition.

Results of the session’s “stand pat” attitude on the racial issue were seen as the reasons for the petitions and for the vote in favor of “rotation.” The congregational action (favored by 932 of the 1,530 voting) provided that the oldest elders would be the first to be replaced.

In the same meeting at which they received the petition, the elders hammered out a policy of admitting Negro worshipers and providing them segregated seating.

During the months-long debate over the issue, no policy was ever adopted that excluded Negroes as such. But officers strictly enforced a policy excluding “demonstrators.” Racially mixed groups protesting segregation repeatedly appeared at the church only to be turned away.

The demonstrations reached a climax last spring after the denomination’s General Assembly turned back proposals to change the 1965 meeting place. At the same time, Senator Richard B. Russell, brother of Pastor Henry E. Russell, was leading the opposition to the then-pending civil rights bill in Washington.

The pastor of the denomination’s third-largest congregation ended his long silence on the issue in January and asked for an end to any policy that might exclude persons from worship services. The vote for rotation was the congregation’s response.

ARTHUR H. MATTHEWS

Campus Centennial

The close of the Civil War found groups of Baptists from northern states traveling south in an effort to set up schools for newly emancipated Negroes. In Washington, D. C., they established the National Theological Institute and Wayland Academy. In Richmond, they founded the Richmond Theological School for Freedmen. These and other schools, including the Free Will Baptists’ Storer College in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, have through a succession of mergers become one and are now known collectively as Virginia Union University.

On its campus in Richmond last month, the university marked its centennial. The highlight was the formal launching of a $1,500,000 development campaign to finance major construction projects.

Virginia Union University now has a full-time enrollment of about 1,200 students, almost all of whom are Negro although there has never been an official no-white admissions policy. There are currently some twenty-five students in the School of Theology. A number of Baptist groups still contribute financial support.