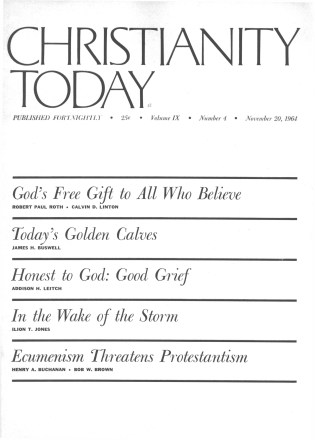

The good Bishop of Woolwich, John A. T. Robinson, has started something he will be a long time getting stopped. He turned out a book that became a best-seller in no time at all. Now he has the difficult task of explaining himself. It’s a pity, in a way. The poor man will be spending years now saying, “I didn’t mean that” or “I didn’t mean it that way.” In a second little book, Christian Morals Today, comprising a series of lectures given in October, 1963, in Liverpool Cathedral, Robinson reflects upon his difficulties. He remarks rather plaintively, “I tend to classify my engagements at the moment by whether they were contracted before or after the flood—the date of the flood for archaeological purposes being the 19th of March 1963.” It is not difficult to understand what he means. Response to his book has broken out in all kinds of places and with every degree of approval and criticism.

We might strike a rather plaintive note, too. It looks as if we shall not rid ourselves of Bishop Robinson for a long time to come. One thinks of old Origen, who warned against saying anything gymnastikos, to which our word “gymnasium” is related. He was warning us against saying something in conflict that we might have to defend, even though we hadn’t planned on the conflict in the first place. We all do this. We get something said, and then, since it is our own brainchild, we feel called upon to defend it to the death, even though it didn’t mean a great deal to us when it all started. One of my friends still thinks that Robinson was writing “tongue in cheek.” Whether this be true in some parts of his book I can only wonder. One thing is certain: if the Bishop had to do it over again, he would have to write a bigger book with much sharper definition and fewer inconsistencies. This is why I suppose he will have to spend the rest of his days answering in the press, clarifying and defining on radio and television, and giving lectures on various points of his position. The rest of his days he will hear the “patter of little feet” (what quarterbacks hear in American football), and he will never know when he is going to be hit from the blind side.

The book, as we all know, is popular from its choice of title to its last illustration. It is very well written and commands attention from men and women in all walks of life. In these ways the book is an unqualified success. Theologically and religiously it could be a disaster.

The book is scripturally unsound. Robinson very plainly rests his case on many recent theologies, primarily those of Tillich and Bultmann. (It would be interesting to know whether either of these great thinkers accepts Robinson as a proponent of his position.) Since he has chosen to build on these two men, he must know, and his readers ought to know, that the scriptural position of both Tillich and Bultmann, however much it may be acceptable in some circles, is highly debatable in others. And it is definitely a sharp breakaway from the position of Scripture and of every church, including the Bishop’s. No church and no creed is ready to accept the stance that this Bishop in the Anglican church has chosen for his own. It is even highly debatable whether Barth’s view has been accepted as a creedal position by any denomination, and of course Barth represents another position over against the Bishop’s. In other words, Robinson represents a theological position of a minority group, even in terms of a shift from the old orthodoxy into neo-orthodoxy. This in itself makes him highly suspect and raises puzzling questions, first, about his wide acceptance, and second, about the willingness of his church to let him continue officially and publicly with what he has to say.

The Bishop And The Bible

Even if we identify his position with that of Bultmann, he does not throw his emphasis where Bultmann throws his; Bultmann’s “New Testament Theology” rests on Paul and John with virtual discard of the Gospels, while Robinson continues to look for what sound like “proof texts” wherever they light at hand. And what shall we say of his use of that Scripture which he does accept? One illustration will do. In speaking of the prodigal son he emphasizes that the boy in the far country “came to himself.” This is far enough for Robinson to prove his case that the God “down there” or even “in there” is nothing more than the ground of our own being. He interprets “came to himself” in his own peculiar way, while evading the fact that in the same parable the boy “came to his father.” Robinson is not above using Scripture to suit his thesis and can twist the story of the prodigal son to prove that a man’s reconciliation, in the long run, is to himself and not to God. This sets before us very bluntly the plain fact that the God of Bishop Robinson does not look much like the God of Scripture.

The book is theologically thin. In addition to playing fast and loose with any understanding the Church has had regarding God and the Fatherhood of God, Robinson gives no solid treatment of man or of sin, or of the Redeemer and the Christian hope. Although he tries to clarify theology by a shift in terms, his introduction of new terms leads only to greater confusion. It is hard to see what is gained by a change of vocabulary in theology anyway. Words have been hacked out by hard debate during centuries of church history, and they have their value as coin of the realm. To introduce his own vocabulary—such as “Ultimate Reality” or “Ground of Being” for God—does not really clarify. Rather, it demands now, and will certainly demand in the years to come, endless explanation. If the problem is that biblical and creedal language have been forced into anthropomorphic terms, do we not recognize that the Bishop, in his own struggle for new language, is forced in the same direction? His book would not have been possible without his concern for popular language; the trouble is that his own popular language lacks the exactitude of the words of long usage. His terms, and even the ideas they convey, are really useful only to scholars well grounded in philosophy. On his own terms the Bishop digs up more snakes than he can kill.

The book is philosophically superficial. If the problem we face is how a living God can at one time be both transcendent and immanent, then Robinson gives us no new answer. He shifts the ground from transcendence to immanence and thereby seems to deny the being of God or the person of God, except in and through people. The normal shift of such thinking will land him eventually in pantheism. Spinoza had the same problem. Surely the Bishop knows that this question is as old as Western thought. A variation of it divided Plato and Aristotle as they struggled with universals versus particulars. Plato’s solution was that a thing like “Beauty” has its own reality, whether we do or do not have “beautiful things.” Aristotle argued that there are beautiful things for which the term “Beauty” is simply a name and not a reality. Significantly, in their later writings Plato tended toward Aristotle and Aristotle toward Plato, for both faced the mystery of how ultimate reality participates in the individual item or how the individual item participates in reality. There seems to be no answer to this mystery for minds like ours, but we should not dismiss the mystery of the structure of reality by dismissing one or another of the two truths that created the mystery.

This old argument dominated philosophical debate in the Middle Ages and did not down in the breakthrough of the Renaissance. Such great thinkers as Kepler, Galileo, and Newton hoped that man could escape the tyranny of revelation by giving attention to things as they really are on this good earth. Humanism and science both focused on the here and now. Galileo tried with all his might to make all relations mechanical and mathematical, and all these men gave wonderful impetus to science in the new day. But their mechanisms would not stand still. They were caught in the problem of first cause for the series of cause and effect. When they tried to examine nature purely objectively, they could not escape the subjectivity of the examiner. This Descartes made plain. No one can concentrate on “beings” without eventually having to consider “Being.”

We still find the mystery beyond resolution in a far greater book than Honest to God. A far greater bishop than Robinson, William Temple, made it plain in Nature, Man and God that the objective examination of nature leads to the examination of man in nature, which leads to the transcendence in man as such and finally to the transcendence of God. Western thought has had to resolve the mystery of being in one of three ways: by making God everything (Spinoza), or by making God nothing (the positivists of our day), or by accepting a Being who is all in all but who, nevertheless, has the power beyond our powers to set over against himself other beings. Robinson, who knows better, has tried to tell us that we must from now on resolve the mystery by denying to God his existence.

Interestingly enough, the biblical revelation was already ahead of the philosophers as early as the call of Moses. The Bible as usual does not explain philosophically but allows the truth to stand as it is: the God who calls Moses from the burning bush is no other than “I am that I am that I am” (God of all being), and he is also the God of “Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” who enters into personal covenant relations with his people.

The Theological Question

How God does all this we do not know. That he does it we must endlessly maintain. The theological question, not the theological answer, is this whole wonderful structure of reality, a God who is Everything, able to create us as something over against himself and to sustain us by the Word of his power. The question runs through the whole of reality, not only in the mystery of creation “out of nothing” into something, but in the marvelous inner relations between God and his people in sovereignty and freedom, in inspiration and response, in prayer and in providence. To usher all this out in order to satisfy “the modern man” (whatever he is) is to offend both sound philosophy and joyful, hopeful religion.

Wilhelm Windelband, speaking of another matter in his History of Philosophy, lends us words and thoughts for this subject before us: “The nature of man consists in the inner union of two heterogeneous substances, a mind and a body, and this marvelous (metaphysically incomprehensible) union has been so arranged by God’s will that in this single case the conscious and spatial substances act upon each other.” Windelband is speaking of man, but he is illustrating the mystery of which we have been speaking—the marvelous union of two realities, neither of which can be denied and both of which, in some sense, are interlocked. If we would back up Paul’s emphasis on union with Christ, we would recognize how Paul is most himself when he is able to say, “For me to live is Christ,” or again, “It is no longer I that live, but Christ liveth in me.” This denies neither the existence of Christ, nor the existence of Paul, nor the union of both. Paul is not lost, but his whole life is enhanced. So also the illustrations are valid of husband and wife, of foundation and building, of vine and branches. We must think afresh, beyond Robinson and his ilk, of the mystery of our being, which can hold to the individual persons and the union at the same time. This kind of thinking will serve us in other problems, such as the person of Christ and the nature of the Trinity.

The book is ethically naive. Bishop Robinson is not the only writer of our time to keep hammering away at legalisms and moralisms in order to establish the ethic of love. Long ago Aristotle raised a nice question against Socrates’ emphasis that “knowledge is virtue.” “Yes,” said Aristotle, “but what of the passions?” What of the passions indeed? What about sin? If we believe the Bible instead of Robinson, sin is a condition, and the natural man needs to be born again. In his lost condition he is incapable of obeying God, and even in his saved condition there is still “the old Adam.” The law is our safeguard for ourselves and for others and for our relations in society. Even for those who would be governed entirely by love, “What of the passions?” My most loving acts are discolored by a conflict of motives and a readiness to rationalize. I am not willing to believe, even if Robinson does believe it, that love alone will control a young couple as they decide their behavior. “After all,” they say, “we love each other”—but I say, “What of the passions?” They each will contribute personal rationalizations in determining their behavior. “After all,” they say, “we love each other”—but do they at the same time love their parents, their possible children, the society that has nurtured them and to which they owe a contribution? As Richard Lovelace put it, “I could not love thee, Dear, so much, loved I not Honor more.” Even the greatest love needs a point of reference above or beyond itself.

When To Walk Away

More than this, the law is the “schoolteacher toward Christ.” There is no question whether we are to move toward that freedom with which Christ set us free. The only question concerns the point at which any of us can say that he is ready to walk away from his teacher. My own judgment is that love will motivate us to keep the law, and that any love we express will never be apart from the law, although it can be beyond the law. The fact that I love my wife does not mean that I have no requirements laid upon me in my relationship with her. It does mean, happily, that in the positive expressions of love I may blow the lid off the bonds of the law. I can always do more than the law requires, but never less. Robinson is very naïve and reflects his loose use of Scripture and therefore his superficial view of sin, if he thinks that any segment of Church or society is ready to break away from the law.

The book is a frightening symptom. Since it is short, even Robinson is aware, as we with every sympathy are aware, that he couldn’t say everything about everything. But because it is a short book and an incomplete book, it is a poor guide for theology or ethics. What is disturbing, of course, is its enthusiastic reception by all kinds of people. In a book entitled The Honest to God Debate, Robinson tells “why I wrote it”: he says, “The traditional imagery of God simply succeeds, I believe, in making Him remote for millions of men today.” I don’t believe that Robinson makes God any less remote. Men have received this book from a bishop of the Anglican church, not to clarify their faith, but, in many, many cases, to support their unbelief. It sounds particularly good coming from a bishop, but they knew all along that much of this religious stuff was nonsense.

The book is a symptom, moreover, of the genuine ignorance, not only of the man on the street but of confessing Christians, about the faith. This very superficiality makes Honest to God sound much more plausible than it is.

A further symptom of the times is that a bishop who on the one hand has promised “to teach and exhort with wholesome doctrines” and “to banish and drive away all erroneous and strange doctrine contrary to God’s Word,” and who on the other is able to say that John’s statement, “The Father sent the Son to be the Saviour of the world,” or Paul’s statement, “There is one God, one mediator between God and men …, who gave himself a ransom …,” are merely mythology—that such a man still holds office in a creedal church, that he is not banished for heresy and apparently cannot be banished for heresy. This is indeed a strange, strange thing. I am beginning to believe (and some would think this a happy fact in our day) that it is virtually impossible for a man to be removed from church membership or church office for heresy. The reason is probably that to be a heretic a man has to take a stand in opposition to a fixed body of truth, and no church seems to have the conviction any more to say what that body of truth is. We can be Anglicans “in general,” which means that eventually we can be Christians “in general,” which means that the doors are wide open to universalism and eventually to a world religion of eclecticism.

That the Church needs new power and new direction no one can deny. That Bishop Robinson believes he has caught hold of a useful handle for increased leverage, no one can deny. But I think he is fundamentally wrong if he believes that by changing the language to fit the day—or, more specifically, by changing the thought by changing the language—he will somehow make the Gospel more palatable. The problem of the Church is not to listen to the world and thus adjust the Gospel; it is to get the world to listen to the Gospel, which is eternally and everywhere true.