This essay comes out of the experience of a working Christian artist who has for many years admired and enjoyed the great schools of religious painting and the moving and beautiful compositions of the master composers. My earliest recollections go back to my boyhood in a little Nebraska town and to the small Presbyterian church where my mother and father sang soprano and tenor parts in the quartette. Many a night I fell asleep while choir practice was being held downstairs, where a framed print of Millet’s “Angelus” hung over the Estey organ. Toward Easter the quartette was augmented and sang “The Seven Last Words,” In December I was lulled to rest as the choir rehearsed “Silent Night” and “Joy to the World.” Later I pumped the organ in church and thrilled to the organist’s dexterous conquering of the difficulties of Bach on the wheezy old instrument.

As my voice changed, I drifted away from music to graphic art, copying Millet’s “Angelus” and the Charles Dana Gibson drawings in magazines. My voice returned to an unstable tenor; but when I went off to study art at the Chicago Art Institute and the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, I tried voice coaching and learned solo parts in The Messiah and Elijah.

During these Chicago days, and as I was later becoming established as a painter in the East, my wife and I lost our way spiritually. I had gone through a phase of Unitarianism, a trial at Christian Science, and even an experiment with crystal-ball séances. But one evening an older artist, a devout Quaker, came to our apartment and quoted that striking supernatural passage from First Thessalonians about the Lord himself descending from heaven with a shout. So arresting was his faith in such an event that we began to attend a little chapel he recommended.

The place was small, but the pastor was so devoted an evangelical with such real Christian faith that soon we were on our way to a true knowledge of the Bible. I heard again the hymns of my youth, sung by dedicated people and played as written by a young lady who had not gone to a class in “how to play for gospel singing” and who refrained from the embellishment of arpeggios up and down the suffering piano. A lady near me sang one of the hymns that took me back over the years; I was a child again, and all the simple truths of the Sunday school, the remembrance of music and worship and faith, swept over me in that chapel. We found the Lord there. So it was that I, a painter, was helped to know Christ through the sister art of music.

A Christian artist of considerable ability said recently that he believed it impossible to create fine Christian painting in this modern age. I do not agree. The low estate of Christian art stems from the fact that very few talented artists undertake to paint Christian subjects and that most of those who work in this field lack the power and dedication to make masterpieces. There is no question that our speed of living, the distractions of our mechanized and science-geared age, do not tend to encourage work in the fine arts. But given the talent, the character to manage and drive that talent, a man of godly integrity and genius could surely respond to the biblical challenge and create his masterpiece even in these times.

The early Christian works, from the great Byzantine mosaics, the frescoes, the astonishing flowering of Italian painting in Duccio, Giotto, Mantegna, Massacio, Michelangelo, Da Vinci, and the masters of Flemish and German painting, would seem productions of such towering strength as to discourage men from following them. Let us look, however, with particular admiration at Rembrandt, an artist of gigantic stature despite the lack of papal or baronial sponsor. Here was a man who gave up a career of painting portraits at fat fees and died a pauper, but who was his own master, beholden to no mortal, and a creator of supreme art in three mediums. His biblical drawings, his etchings, his paintings—each of these alone stamps him as a master. To cite only two paintings, his “Supper at Emmaus” in the Louvre, and his “Head of Christ” in the Metropolitan Museum have the sublime light, the character of Christ, his humanity, and his absolute Deity powerfully wrought into living masterpieces.

The painter who has talent and is a Christian will find inspiration and take fire from Rembrandt. He will also say, in the light of the great early masters and in comparison with Rembrandt, “We in our day are pygmies.” But let us not be downhearted. Let the ambitious young Christian painter start the day with a time in Cod’s Word, believing and asking God’s help. Let him spend much time with the masters through the museums, or, if he has no access to the originals, with fine books of reproductions of the masters and with large reprints in color. These will help him toward his goal of painting a work of Christian art.

Virtuosity Without Spirit

Such work as that of Salvador Dali will scarcely benefit the Christian artist. Dali is a realistic draftsman with a cold color sense and a gift for self-advertisement, and is, after Picasso, probably the most publicized artist of our day, greatly praised by a certain kind of art criticism. But to me his technical virtuosity creates a religious painting entirely earthy and totally devoid of the spirit that raises the ordinary into the sublime. He astonishes me, but he neither transports nor deeply moves me.

In contemplating the works of lesser-known contemporary painters, I hesitate to speak of their weaknesses. The sentimental heads and figures of Christ that we find in homes, churches, and Sunday schools, so lacking in strength and depth, make me feel that we do better to know and visualize our Lord only through his Word. But who may say or know what spiritual help these weak productions have been to many people? Shall we criticize the chalk talks, with colored lights imitative of Hollywood illuminating phosphorescent paints, accompanied by a running evangelistic commentary? Souls have been saved through such programs. Yet the level of art there displayed could be raised.

How may the glaring lack of taste in graphic art that so often characterizes the rank and file of Christians be remedied? Let me suggest a couple of answers to the question.

First, Christians should be encouraged to go to art museums to study great pictures on biblical themes. If evangelical churches organize roller-skating parties and picnics, why not sponsor fellowship in the arts? This process of attaining a measure of good taste in the Christian use of art will take time, but God will assuredly be pleased at any use of our leisure devoted to bringing inspiration, dignity, and reverence to the worship of our Saviour Jesus Christ through a better quality of art.

Christ As Seen In Art

A wonderful field of enjoyment is open to the Christian who will seek to gain a fuller appreciation of the art of religious painting. What a wide diversity of ideas great artists have shown in their depiction of our Lord! The Byzantine mosaics and the early Italian painters show him as an archaic, stern person. Their primitive style moves us to a feeling of awe as we look at these rigid presentations of the Saviour with no tenderness or compassion in his nature. However, one must feel in them an impressive majesty, an unapproachable other-worldliness. The sculptured Christs enthroned upon the facades of Gothic cathedrals look down from their ancient niches superb in the magic sense of life given to stone by these unknown craftsmen-sculptors.

Then there are the great painters of Italy—the primitive authority of Cimabue and Duccio, passing into the early Giotto and Fra Angelico and Piero della Francesca with the coming of tenderness into Christian art without loss of strength, and moving on through Mantegna, Masaccio, Michelangelo, Titian, Raphael, Veronese, who portray the gamut from the Christ of humility to the regal, lordly Christ of the Venetians; the portrayals of the crucified Lord, the depositions, the pietas of early French painting, northward to the superb Flemish Van Eycks, Rubens, and the Germanic Albrecht Dürer. All these almost countless delineations of the Saviour bear the stamp of nationality. The Italian, French, Flemish, and German painters make him one of them. El Greco, despite his Greek origin and Italian training, identifies Christ with a tortured Spanish school.

Strangely, the Bible does not describe in detail the Lord’s physical appearance. Yes, he is “a man of sorrows” and he weeps; his feelings are disclosed, but not his physical features. It is as though God desires that we worship his Son for his Deity and his Saviourhood alone.

Secondly, and perhaps more important, there is the personal practice of art. Those who have even the slightest desire to try their hand at making pictures should not hesitate to do so.

During my years of teaching and lecturing on art in universities and colleges and before women’s clubs across the country, people of all ages have come to me with questions about what they might do, how they could begin to draw or paint and thus satisfy their creative urge. This very urge is an indication of talent. (Somehow the word “urge” has been strangely neglected in definitions of talent.) There are varying degrees of ability; but whether the talent is great or small, there are endless rewards and enjoyments ahead for those who keep trying. Nothing stimulates appreciation so much as realizing just how artists have created their works.

Everyone has pencil and paper; endless subjects are all around us. It is a good plan to begin with objects in the home, to set up a simple still life—an orange on a round plate for study in circles, curves, and ovals, or a small oblong box or book for practice in long and short straight lines, angles, and square corners. If one hesitates to go it alone, all bookstores and art shops have inexpensive beginner’s manuals to start one on his way.

Religious pictures should not be undertaken unless there is a compelling urge in that direction. God’s world is alive with hills and trees in praise of him, with home life, children, cats and dogs and birds. Despite feelings of inadequacy, the courage to persist brings its reward. We learn by our mistakes. Searching for ways to improve by doing the subject over and over spells progress.

Those who find that they lack the industry and vitality to continue toward professional excellence will not have wasted their time. For the rest of their lives they will see nature in a new light; their sense of color will be better, and their enjoyment of museums and prints and books will be much keener and more understanding.

Whether the artist be a professional or a beginning amateur, he must never forget that it is not nature that is put down on paper or canvas. God has created nature in great perfection; we can only draw or paint in symbols that reveal our ideas and feeling about nature. One cannot put a tree down upon paper, but he can learn to draw lines describing its trunk which, through long practice, will enclose something as solid-looking as the tree itself. There are no lines in nature; we invent them. Later one may add tone and color to his tree, a minor miracle if he has genius.

Some years ago at one of my lectures in a Virginia college a farmer’s wife became excited as she watched me do a demonstration of painting. She had never painted anything except kitchen chairs. But she bought some paint and canvas boards and began to paint familiar people, animals, and the scenes she knew so well. On my second visit to Lynchburg I was delighted to see her pictures, finding her style to be that of a pure primitive. I advised her to avoid teachers and continue to do things she loved; later I was able to interest a New York art dealer in handling and selling her work. Here is an unusual and special talent. Few will be like her, but many may have great enjoyment in drawing and painting the subjects that are of interest to them.

Christians will do well to spend more time in raising their level of art appreciation. Art, whether that of the great masters or the humbler efforts of lesser talents, belongs to those things God has given us to enjoy. And in its truest integrity it exists for the glory of God. We need architecture that fittingly houses places of worship, music that worthily praises God the Father and brings men closer to God the Son, pictures on the walls of our homes that, while not necessarily religious, are examples of good art. We need Christian artists of dedicated talent who will extend their horizons in humility and devotion to the true praise of the Giver of talent, who is best honored by the faithful use of his good gifts.

Words For God On The Soviet Stage

During my concert tour of the Soviet Union in 1962, I had two unusual opportunities to carry God’s Word to godless Russia. The first occurred in Leningrad where I sang the Mephistopheles role in Faust. As the curtain came down and I walked off-stage into the wings, the male and female chorus began to applaud and shout the Russian equivalent of “Bravo, comrade!” I stopped, feeling somewhat embarrassed before this palm-pounding praise, and raised my hand to say in full operatic voice: “Thank you, but praise Almighty God, not me.”

The second such incident came at the climax of the tour in Moscow when I sang the title role of Boris Godunov before a Bolshoi Theatre audience that included Premier Khrushchev. At the end of the opera, Boris exclaims, “Forgive me, forgive me”—and falls dead. But suddenly I decided to do a little more. After saying the regular words, I smiled, raised my eyes, and added, “Oh, my God, forgive me.” As I performed it, Boris Godunov finds the peace of God when he dies; in the performance that evening before thirty-five hundred Russian music-lovers the opera ended on a high religious note. That is why, I feel, for the first time in the history of the Bolshoi there was sudden inspired applause even as Boris fell rather than after the final curtain had rung down.

A decade ago, I found the greatest friend in the world. I found Jesus Christ. And the thing I want to tell everybody is that Jesus Christ is not just a philosophy to live by. He is that same living Person who was resurrected nearly two thousand years ago.—JEROME HINES, from the book Faith Is a Star, written and edited by Roland Gammon. Copyright, ©, 1963 by the Southern Baptist Convention Radio and Television Commission. Reprinted by permission of E. P. Dutton.

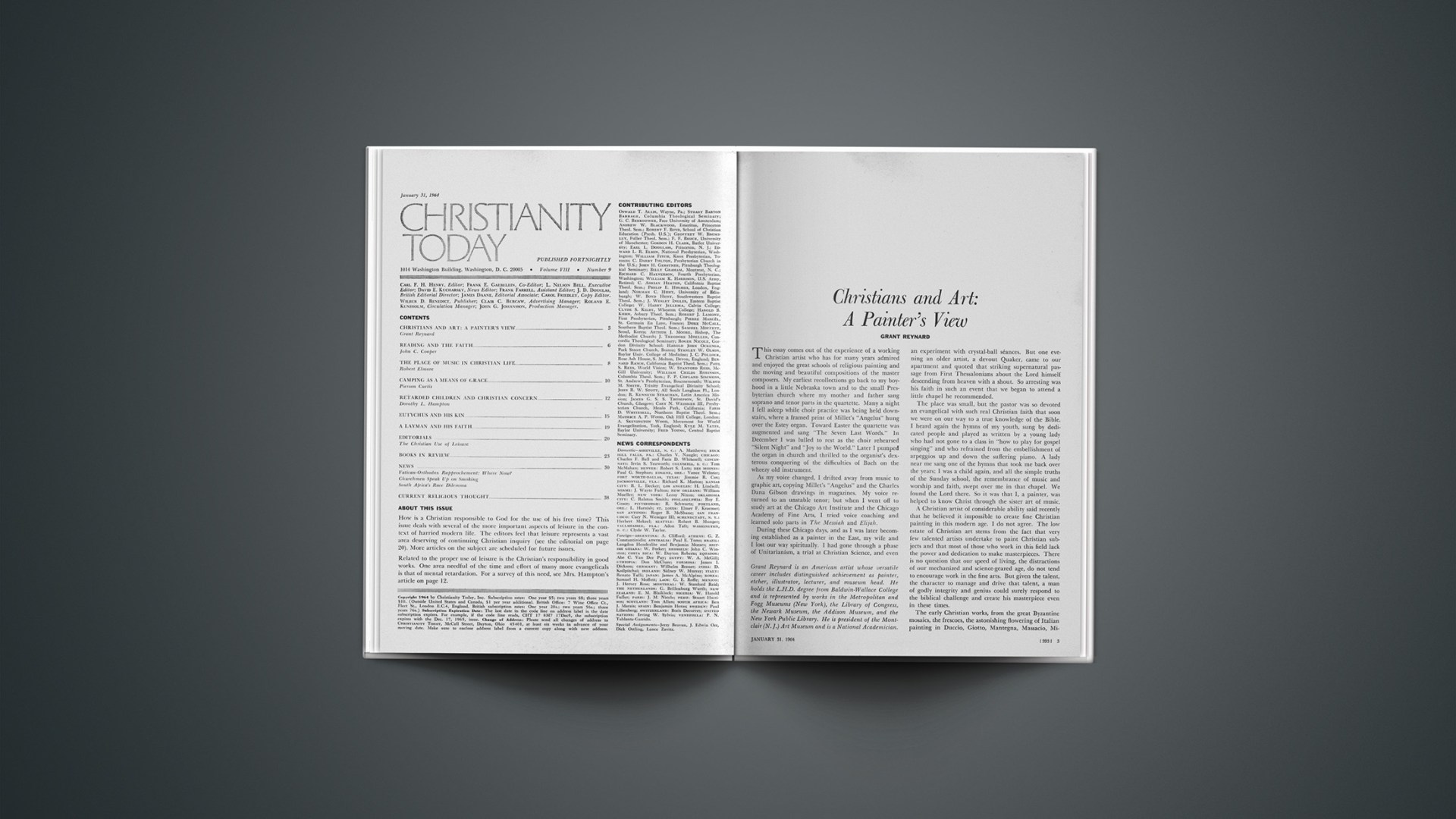

Grant Reynard is an American artist whose versatile career includes distinguished achievement as painter, etcher, illustrator, lecturer, and museum head. He holds the L.H.D. degree from Baldwin-Wallace College and is represented by works in the Metropolitan and Fogg Museums (New York), the Library of Congress, the Newark Museum, the Addison Museum, and the New York Public Library. He is president of the Montclair (N. J.) Art Museum and is a National Academician.