I once heard of a minister who after a term in the United States chaplaincy threw away his library. Fortunately, not many ministers would follow this example. Those who proclaim the Word of God recognize the absolute necessity of books and find it hard even to conceive of a vital Christianity that lacks the stimulus of Christian writing.

Christians are not only “people of the Book,” but people of books, in general. Babylonian libraries shaped the ancestors of Abraham, Egyptian papyri educated Moses, Greek classics and Hebrew commentaries honed the mind of Paul. In time the Book of books became the center of a whole field of literature. As the Gospel confronted the world, the church fathers set forth their faith and defended it against attack through what came to be deathless writings, like Justin Martyr’s Apology, Athanasius’ Defense Against the Arians, and Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo. When the Goths were knocking at the gates of Rome, Augustine envisioned the spires of The City of God rising from the rubble of the dying empire and in his multitudinous literary works laid the foundations of Christian thought for succeeding centuries.

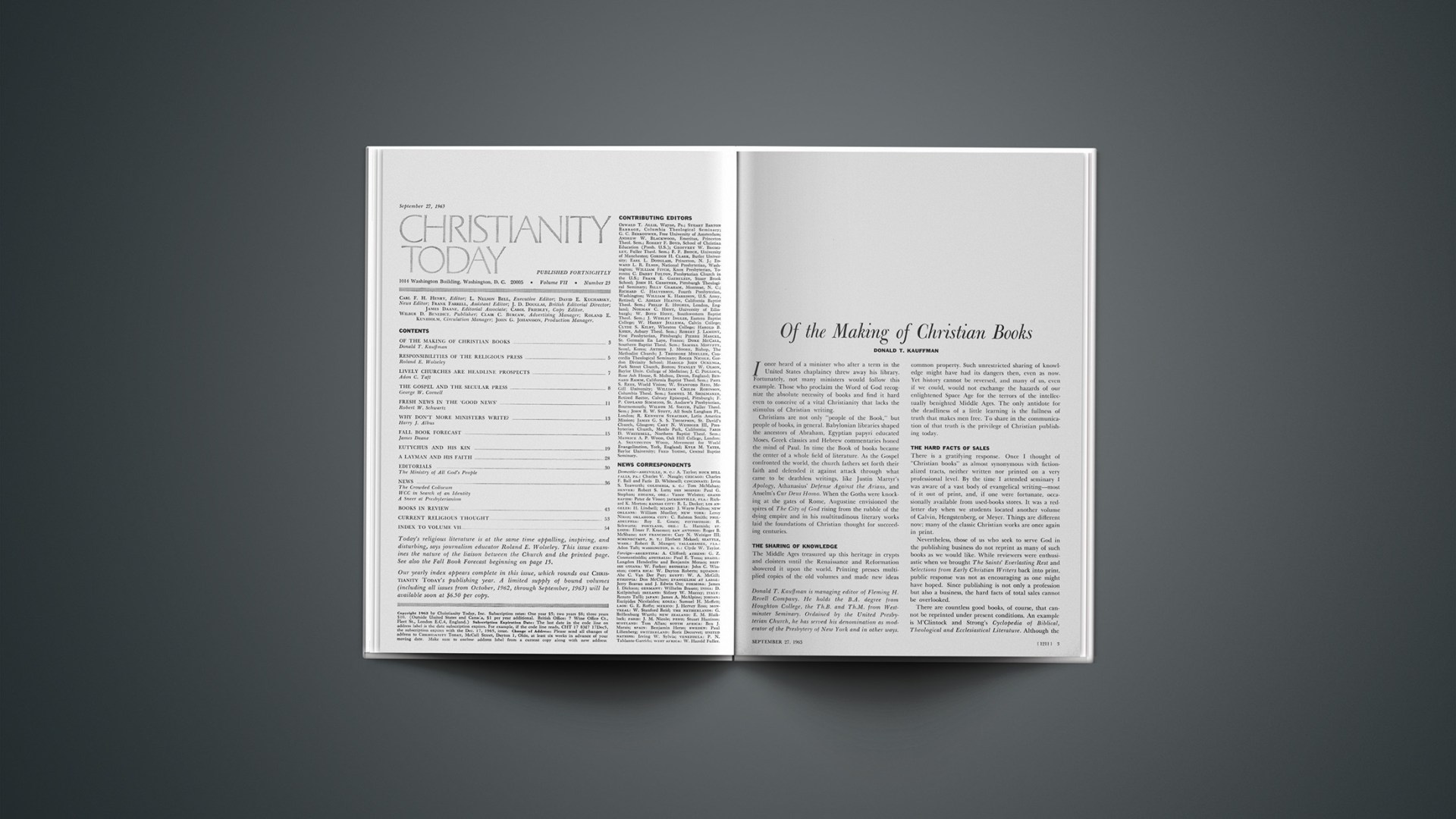

The Sharing Of Knowledge

The Middle Ages treasured up this heritage in crypts and cloisters until the Renaissance and Reformation showered it upon the world. Printing presses multiplied copies of the old volumes and made new ideas common property. Such unrestricted sharing of knowledge might have had its dangers then, even as now. Yet history cannot be reversed, and many of us, even if we could, would not exchange the hazards of our enlightened Space Age for the terrors of the intellectually benighted Middle Ages. The only antidote for the deadliness of a little learning is the fullness of truth that makes men free. To share in the communication of that truth is the privilege of Christian publishing today.

The Hard Facts Of Sales

There is a gratifying response. Once I thought of “Christian books” as almost synonymous with fictionalized tracts, neither written nor printed on a very professional level. By the time I attended seminary I was aware of a vast body of evangelical writing—most of it out of print, and, if one were fortunate, occasionally available from used-books stores. It was a red-letter day when we students located another volume of Calvin, Hengstenberg, or Meyer. Things are different now; many of the classic Christian works are once again in print.

Nevertheless, those of us who seek to serve God in the publishing business do not reprint as many of such books as we would like. While reviewers were enthusiastic when we brought The Saints’ Everlasting Rest and Selections from Early Christian Writers back into print, public response was not as encouraging as one might have hoped. Since publishing is not only a profession but also a business, the hard facts of total sales cannot be overlooked.

There are countless good books, of course, that cannot be reprinted under present conditions. An example is M’Clintock and Strong’s Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature. Although the seventeen million words of these twelve volumes are not to be found anywhere else, the market to absorb the costs of such a massive republishing venture is not apparent. While it grapples with the slowly but steadily rising costs of labor and materials, the publishing industry nonetheless talks hopefully of a breakthrough that will make such projects possible. Meanwhile, we use what opportunities the situation offers.

Of necessity publishing is a partnership between those of us who “make something public” and the public. Readers of CHRISTIANITY TODAY probably know and value the importance of Christian books. But to advance and grow, Christian publishing needs the active support of good books by many more people. Christians need to read without necessarily accepting all reviewers’ verdicts. Christians might profitably engage in more book browsing, personally sampling the wealth of spiritual treasure now available as never before. They might well emulate the pastor of a small rural church whose wife worked to supplement his meager income; when we discussed a new Bible commentary, he said, “I’m going to buy it on faith.”

Better Books Are Needed

All the media of communication seem tinged by the rising tide of lust and violence. To protest this trend is not enough, for when one evil spirit is driven out, seven worse demons take its place. Christian laymen and leaders may achieve more effective results by promoting better radio programs, better television, better newsstand literature, and better books.

I have been surprised at the influence of a casual recommendation of a book. It was through just such word-of-mouth recommendations that I first became acquainted with the writings of C. S. Lewis and J. B. Phillips. Likewise the enthusiasm for particular books which I have voiced in sermons and Bible study groups has brought inquiries and even sales. By speaking a word in season, ministers can do much to inform and train their laymen in profitable reading.

Some churches promote the purchase of good books by budgeting an annual fund for both the minister’s library and the church library. And those who buy gifts for friends, for Sunday school classes, or for church-connected awards should not overlook Christian books.

At the present time we seem to be formulating a new type of missionary literature. Few missionary books of the past compare, for example, with Elisabeth Elliott’s The Savage My Kinsman or Sara Perkins’ Red China Prisoner. Each of these books tells its own exciting story; each is a genuine contribution to a specific area of contemporary concern. Authors of the new missions literature are both daring and intensely dedicated; they are devoted not to exporting American culture under a religious guise but to imparting the reality of the living Christ.

It is good to see such books, and others like them in other fields, succeed. Impressive, too, is the current enthusiasm for new translations of the Scriptures, for new aids to Bible study, for new applications of Christian faith to daily living. Similarly gratifying is the long-established and continuing appeal of classics like Daily Light on the Daily Path, Egermeier’s Bible Story Book, The Children’s Bible, The Child’s Story Bible, and The Christian’s Secret of a Happy Life, as well as of the old, tried, and true translations of the Bible.

Seeking New Scribes

Another invaluable partner of the publisher is the author. For each generation the Word of God must be interpreted afresh so that Jesus Christ may be Lord of all. The search for new authors, new manuscripts, and new ideas is a constant one among publishers. For the most part, all manuscripts and queries receive sympathetic consideration. While a publisher is interested primarily in the content of a book, to estimate its possibilities he also likes to know something about the author’s identity, background, qualifications for writing a book of this type, and so on. A personal interview is not necessary to “sell” oneself or one’s work to a publisher. If an author cannot communicate the essential facts by letter to the editor, the likelihood of his communicating any more successfully with readers through the printed word is rather slim. No matter how a manuscript is presented, it must be examined before its usability can be determined. Manuscripts submitted only in carbon are difficult to read and present a psychological deterrent to acceptance.

Many queries come to a publisher’s desk. Sometimes they say little more than this in effect: “I have written a book entitled ——. Enclosed is a list of the chapter headings and a recommendation by the Reverend ——. May I submit the entire manuscript?” Such queries are not very useful. Neither are brief, cryptic outlines. On the other hand, valuable time is often saved for both author and editor when the writer introduces himself, outlines as clearly as possible what he proposes to write about, and submits two or three well-prepared chapters. Guided by such material, an editor can determine with some precision whether he should take the time to examine the entire manuscript.

Of the thousands of new books to be published this year, many will have Christian themes. Let us hope that the issuance of some of these will inaugurate as felicitous a chain of events as Fleming H. Revell’s publication many years ago of the first book by a lanky young Britisher named G. Campbell Morgan.

Books, said John Milton in Areopagitica, his magnificent seventeenth-century defense of the freedom of the press, “preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them.… revolutions of ages do not oft recover the loss of a rejected truth, for the want of which whole nations fare the worse.”

Readers, writers, and publishers can be a triple alliance in making known and preserving what is best in Christian thought for the benefit and blessing of all mankind.