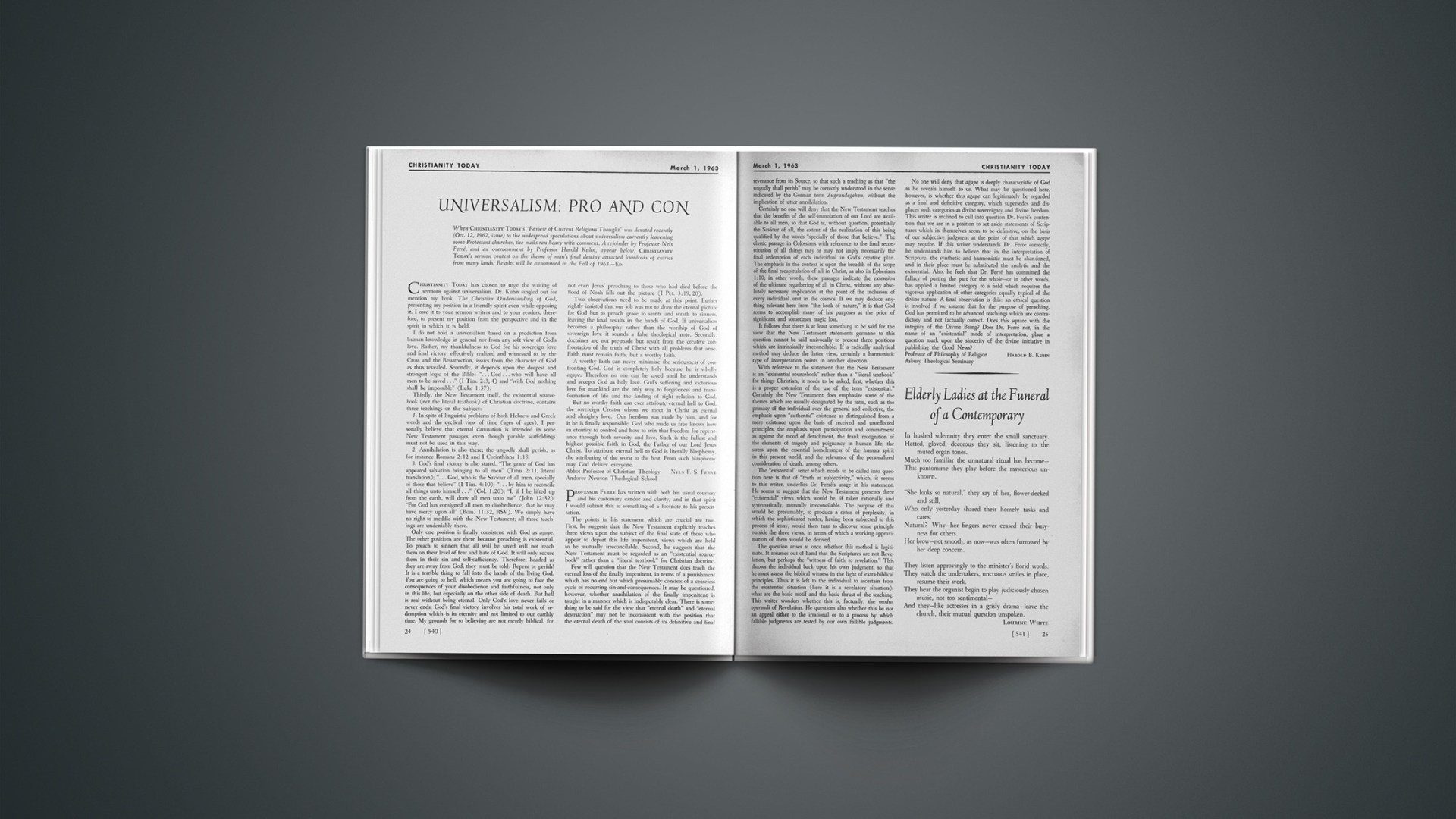

WhenCHRISTIANITY TODAY’S“Review of Current Religious Thought” was devoted recently (Oct. 12, 1962, issue) to the widespread speculations about universalism currently leavening some Protestant churches, the mails ran heavy with comment. A rejoinder by Professor Nels Ferré, and an overcomment by Professor Harold Kuhn, appear below.CHRISTIANITY TODAY’Ssermon contest on the theme of man’s final destiny attracted hundreds of entries from many lands. Results will be announced in the Fall of 1963.—ED.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY has chosen to urge the writing of sermons against universalism. Dr. Kuhn singled out for mention my book, The Christian Understanding of God, presenting my position in a friendly spirit even while opposing it. I owe it to your sermon writers and to your readers, therefore, to present my position from the perspective and in the spirit in which it is held.

I do not hold a universalism based on a prediction from human knowledge in general nor from any soft view of God’s love. Rather, my thankfulness to God for his sovereign love and final victory, effectively realized and witnessed to by the Cross and the Resurrection, issues from the character of God as thus revealed. Secondly, it depends upon the deepest and strongest logic of the Bible: “… God … who will have all men to be saved …” (1 Tim. 2:3, 4) and “with God nothing shall be impossible” (Luke 1:37).

Thirdly, the New Testament itself, the existential sourcebook (not the literal textbook) of Christian doctrine, contains three teachings on the subject:

1. In spite of linguistic problems of both Hebrew and Greek words and the cyclical view of time (ages of ages), I personally believe that eternal damnation is intended in some New Testament passages, even though parable scaffoldings must not be used in this way.

2. Annihilation is also there; the ungodly shall perish, as for instance Romans 2:12 and 1 Corinthians 1:18.

3. God’s final victory is also stated. “The grace of God has appeared salvation bringing to all men” (Titus 2:11, literal translation); “… God, who is the Saviour of all men, specially of those that believe” (1 Tim. 4:10); “… by him to reconcile all things unto himself …” (Col. 1:20); “I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me” (John 12:32); “For God has consigned all men to disobedience, that he may have mercy upon all” (Rom. 11:32, RSV). We simply have no right to meddle with the New Testament; all three teachings are undeniably there.

Only one position is finally consistent with God as agape. The other positions are there because preaching is existential. To preach to sinners that all will be saved will not reach them on their level of fear and hate of God. It will only secure them in their sin and self-sufficiency. Therefore, headed as they are away from God, they must be told: Repent or perish! It is a terrible thing to fall into the hands of the living God. You are going to hell, which means you are going to face the consequences of your disobedience and faithfulness, not only in this life, but especially on the other side of death. But hell is real without being eternal. Only God’s love never fails or never ends. God’s final victory involves his total work of redemption which is in eternity and not limited to our earthly time. My grounds for so believing are not merely biblical, for not even Jesus’ preaching to those who had died before the flood of Noah fills out the picture (1 Pet. 3:19, 20).

Two observations need to be made at this point. Luther rightly insisted that our job was not to draw the eternal picture for God but to preach grace to saints and wrath to sinners, leaving the final results in the hands of God. If universalism becomes a philosophy rather than the worship of God of sovereign love it sounds a false theological note. Secondly, doctrines are not pre-made but result from the creative confrontation of the truth of Christ with all problems that arise. Faith must remain faith, but a worthy faith.

A worthy faith can never minimize the seriousness of confronting God. God is completely holy because he is wholly agape. Therefore no one can be saved until he understands and accepts God as holy love. God’s suffering and victorious love for mankind are the only way to forgiveness and transformation of life and the finding of right relation to God.

But no worthy faith can ever attribute eternal hell to God, the sovereign Creator whom we meet in Christ as eternal and almighty love. Our freedom was made by him, and for it he is finally responsible. God who made us free knows how in eternity to control and how to win that freedom for repentance through both severity and love. Such is the fullest and highest possible faith in God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. To attribute eternal hell to God is literally blasphemy, the attributing of the worst to the best. From such blasphemy may God deliver everyone.

Abbot Professor of Christian Theology

Andover Newton Theological School

Professor Ferre has written with both his usual courtesy and his customary candor and clarity, and in that spirit I would submit this as something of a footnote to his presentation.

The points in his statement which are crucial are two. First, he suggests that the New Testament explicitly teaches three views upon the subject of the final state of those who appear to depart this life impenitent, views which are held to be mutually irreconcilable. Second, he suggests that the New Testament must be regarded as an “existential sourcebook” rather than a “literal textbook” for Christian doctrine.

Few will question that the New Testament does teach the eternal loss of the finally impenitent, in terms of a punishment which has no end but which presumably consists of a ceaseless cycle of recurring sin-and-consequences. It may be questioned, however, whether annihilation of the finally impenitent is taught in a manner which is indisputably clear. There is something to be said for the view that “eternal death” and “eternal destruction” may not be inconsistent with the position that the eternal death of the soul consists of its definitive and final severance from its Source, so that such a teaching as that “the ungodly shall perish” may be correctly understood in the sense indicated by the German term Zugrundegehen, without the implication of utter annihilation.

Certainly no one will deny that the New Testament teaches that the benefits of the self-immolation of our Lord are available to all men, so that God is, without question, potentially the Saviour of all, the extent of the realization of this being qualified by the words “specially of those that believe.” The classic passage in Colossians with reference to the final reconstitution of all things may or may not imply necessarily the final redemption of each individual in God’s creative plan. The emphasis in the context is upon the breadth of the scope of the final recapitulation of all in Christ, as also in Ephesians 1:10; in other words, these passages indicate the extension of the ultimate regathering of all in Christ, without any absolutely necessary implication at the point of the inclusion of every individual unit in the cosmos. If we may deduce anything relevant here from “the book of nature,” it is that God seems to accomplish many of his purposes at the price of significant and sometimes tragic loss.

It follows that there is at least something to be said for the view that the New Testament statements germane to this question cannot be said univocally to present three positions which are intrinsically irreconcilable. If a radically analytical method may deduce the latter view, certainly a harmonistic type of interpretation points in another direction.

With reference to the statement that the New Testament is an “existential sourcebook” rather than a “literal textbook” for things Christian, it needs to be asked, first, whether this is a proper extension of the use of the term “existential.” Certainly the New Testament does emphasize some of the themes which are usually designated by the term, such as the primacy of the individual over the general and collective, the emphasis upon “authentic” existence as distinguished from a mere existence upon the basis of received and unreflected principles, the emphasis upon participation and commitment as against the mood of detachment, the frank recognition of the elements of tragedy and poignancy in human life, the stress upon the essential homelessness of the human spirit in this present world, and the relevance of the personalized consideration of death, among others.

The “existential” tenet which needs to be called into question here is that of “truth as subjectivity,” which, it seems to this writer, underlies Dr. Ferré’s usage in his statement. He seems to suggest that the New Testament presents three “existential” views which would be, if taken rationally and systematically, mutually irreconcilable. The purpose of this would be, presumably, to produce a sense of perplexity, in which the sophisticated reader, having been subjected to this process of irony, would then turn to discover some principle outside the three views, in terms of which a working approximation of them would be derived.

The question arises at once whether this method is legitimate. It assumes out of hand that the Scriptures are not Revelation, but perhaps the “witness of faith to revelation.” This throws the individual back upon his own judgment, so that he must assess the biblical witness in the light of extra-biblical principles. Thus it is left to the individual to ascertain from the existential situation (here it is a revelatory situation), what are the basic motif and the basic thrust of the teaching. This writer wonders whether this is, factually, the modus operandi of Revelation. He questions also whether this be not an appeal either to the irrational or to a process by which fallible judgments are tested by our own fallible judgments.

No one will deny that agape is deeply characteristic of God as he reveals himself to us. What may be questioned here, however, is whether this agape can legitimately be regarded as a final and definitive category, which supersedes and displaces such categories as divine sovereignty and divine freedom. This writer is inclined to call into question Dr. Ferré’s contention that we are in a position to set aside statements of Scriptures which in themselves seem to be definitive, on the basis of our subjective judgment at the point of that which agape may require. If this writer understands Dr. Ferré correctly, he understands him to believe that in the interpretation of Scripture, the synthetic and harmonistic must be abandoned, and in their place must be substituted the analytic and the existential. Also, he feels that Dr. Ferré has committed the fallacy of putting the part for the whole—or in other words, has applied a limited category to a field which requires the vigorous application of other categories equally typical of the divine nature. A final observation is this: an ethical question is involved if we assume that for the purpose of preaching, God has permitted to be advanced teachings which are contradictory and not factually correct. Does this square with the integrity of the Divine Being? Does Dr. Ferré not, in the name of an “existential” mode of interpretation, place a question mark upon the sincerity of the divine initiative in publishing the Good News?

Professor of Philosophy of Religion

Asbury Theological Seminary

Elderly Ladies at the Funeral of a Contemporary

In hushed solemnity they enter the small sanctuary.

Hatted, gloved, decorous they sit, listening to the muted organ tones.

Much too familiar the unnatural ritual has become—

This pantomime they play before the mysterious unknown.

“She looks so natural,” they say of her, flower-decked and still,

Who only yesterday shared their homely tasks and cares.

Natural? Why—her fingers never ceased their busyness for others.

Her brow—not smooth, as now—was often furrowed by her deep concern.

They listen approvingly to the minister’s florid words.

They watch the undertakers, unctuous smiles in place, resume their work.

They hear the organist begin to play judiciously-chosen music, not too sentimental—

And they—like actresses in a grisly drama—leave the church, their mutual question unspoken.

LOURINE WHITE