In olden times, before there was a Protestant church, the priest or other member of a religious order had a spiritual director to whom he could always take his troubles. Today most Protestant clergymen are not that fortunate. It is a rare denomination indeed that has any adequate ministry to its ministers, although emotional problems of clergymen are on the increase.

I do not want to imply that our Protestant clergymen are any more confused than their neighbors across the street or than those in their congregations. Our rapidly changing morals, standards of commerce, and the quickening pace of day-to-day life are already taking their toll in heightened emotional disturbances among many individuals. Granting that our clergymen are average, normal individuals, they are caught up in the problems and anxieties of the day. Their families are subject to the same stresses and strains. More than ten thousand of our Protestant ministers are now receiving some form of individual or hospital psychiatric care.

Here again I am not trying to prove that there is a vast amount of serious mental illness among our clergy. Actually, there are no statistics proving that there is more emotional and mental illness among clergymen than among members of any other professional group, despite the fact that there has been a threefold increase in the number of ministers in state hospitals. The figures are of particular interest only because clergymen are supposed to be figures of emotional strength and stability in our communities and churches. It must be obvious to anyone who is professionally concerned with physical or mental illness, however, that our clergy, like all other individuals, have problems in these areas.

Over the past several years, as I have worked with clergymen and psychiatrists throughout the country, I have been appalled at the number of clergymen who want to discuss their personal problems. Many of their difficulties are tragic. Some of these clergymen are rapidly becoming alcoholics or dope addicts. Others have fallen in love with another woman and are searching for a way out of the dilemma through divorce. There are other problems just as serious, if not as tragic. Many clergymen are unhappy and realize too late that they are in the wrong vocation. Others are burdened with anxiety and guilt because of their inability to play the part of the supernatural, holy saint that the congregation expects of them. Problems involving their children, their marital relations, and the peculiarities and ills of their aging parents often place intolerable burdens upon many clergymen and help to weaken their spiritual, physical, and mental health. Some clergymen become deeply disturbed when they do not receive an expected promotion. All organizations involve politics and politicians, and I know of one clergyman who became violently embittered when he narrowly lost being elected a bishop on the ninth ballot. Low salaries, frustrated ambitions, and sheer loneliness aggravate a predisposition to serious emotional disturbances that need the help of wise counselors.

Fortunate is the denomination that has a warm ministry to such ministers, but many clergymen complain that their denominations have made no provisions to help them with their personal problems. Most bishops and other heads of religious groups are too busy with administrative and community activities to find time to minister to the troubles of ministers. I have known clergymen to have to wait a month before being able to get an appointment with a bishop. Even when an appointment is granted, there is no guarantee that the church head will have the resources to help the clergyman with his problem or, even worse, to understand it. I have known bishops and other superiors to panic when clergymen revealed to them deep-seated, emotional problems.

In a sense, Protestant clergymen are paying the penalty for being members of a professional group rather than a religious order. Most of our religious organizations are primarily concerned with administrative matters—programs, budgets, church government. One only need look at Roman Catholic religious orders and the pastoral care and supervision provided for those entering the religious life to see the difference between Roman Catholic and Protestant concern for the clergy. In the Roman Catholic Church, once an individual consecrates himself by a vow to God to serve the cause of God and the church and is admitted to the Community of the Ordained, he is taken under the wing of the Holy Church. His problems become the church’s problems, and all are bound in a supernatural order that knits them together with a bond much stronger than that linking members of a family in the natural order. The church accepts the priest for better or for worse. Without the priest the church could not exist, and without the church the priest could not have his holy vocation.

We are becoming more aware that many of our emotional problems may be symptomatic of deeply underlying mental or physical illness. The stresses of everyday living can easily push us into illness, and fortunate is the individual who can obtain good medical and psychological care when he ceases to be at ease with himself. If he is a Protestant clergyman, he is often forced to seek help outside his church, particularly if he is in psychological difficulty. More often than not, fear of chastisement or condemnation by his superior will cause him to bear his burdens alone. Few low-salaried ministers have the courage or funds to consult a psychiatrist.

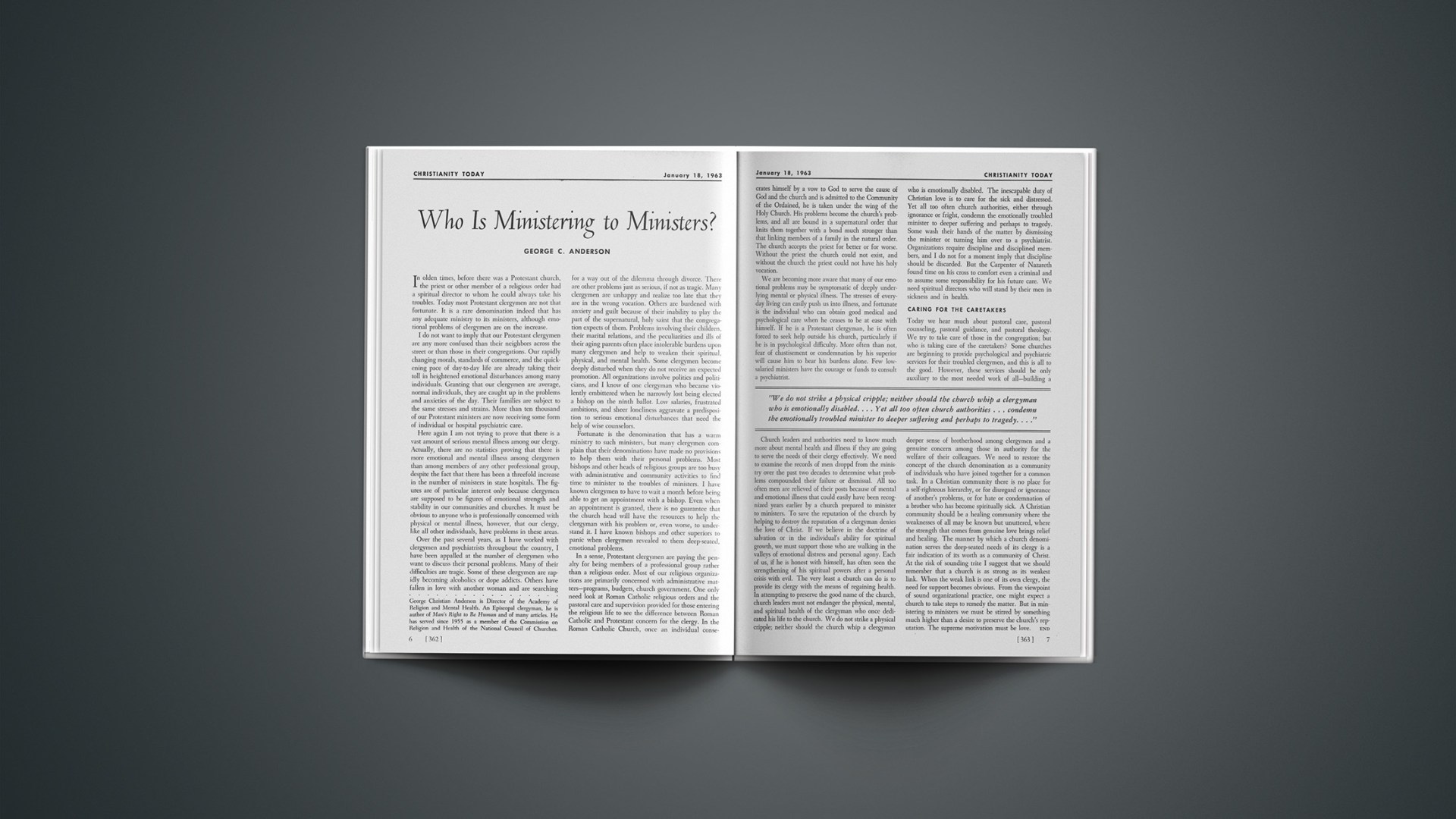

Church leaders and authorities need to know much more about mental health and illness if they are going to serve the needs of their clergy effectively. We need to examine the records of men droppd from the ministry over the past two decades to determine what problems compounded their failure or dismissal. All too often men are relieved of their posts because of mental and emotional illness that could easily have been recognized years earlier by a church prepared to minister to ministers. To save the reputation of the church by helping to destroy the reputation of a clergyman denies the love of Christ. If we believe in the doctrine of salvation or in the individual’s ability for spiritual growth, we must support those who are walking in the valleys of emotional distress and personal agony. Each of us, if he is honest with himself, has often seen the strengthening of his spiritual powers after a personal crisis with evil. The very least a church can do is to provide its clergy with the means of regaining health. In attempting to preserve the good name of the church, church leaders must not endanger the physical, mental, and spiritual health of the clergyman who once dedicated his life to the church. We do not strike a physical cripple; neither should the church whip a clergyman who is emotionally disabled. The inescapable duty of Christian love is to care for the sick and distressed. Yet all too often church authorities, either through ignorance or fright, condemn the emotionally troubled minister to deeper suffering and perhaps to tragedy. Some wash their hands of the matter by dismissing the minister or turning him over to a psychiatrist. Organizations require discipline and disciplined members, and I do not for a moment imply that discipline should be discarded. But the Carpenter of Nazareth found time on his cross to comfort even a criminal and to assume some responsibility for his future care. We need spiritual directors who will stand by their men in sickness and in health.

Caring For The Caretakers

Today we hear much about pastoral care, pastoral counseling, pastoral guidance, and pastoral theology. We try to take care of those in the congregation; but who is taking care of the caretakers? Some churches are beginning to provide psychological and psychiatric services for their troubled clergymen, and this is all to the good. However, these services should be only auxiliary to the most needed work of all—building a deeper sense of brotherhood among clergymen and a genuine concern among those in authority for the welfare of their colleagues. We need to restore the concept of the church denomination as a community of individuals who have joined together for a common task. In a Christian community there is no place for a self-righteous hierarchy, or for disregard or ignorance of another’s problems, or for hate or condemnation of a brother who has become spiritually sick. A Christian community should be a healing community where the weaknesses of all may be known but unuttered, where the strength that comes from genuine love brings relief and healing. The manner by which a church denomination serves the deep-seated needs of its clergy is a fair indication of its worth as a community of Christ. At the risk of sounding trite I suggest that we should remember that a church is as strong as its weakest link. When the weak link is one of its own clergy, the need for support becomes obvious. From the viewpoint of sound organizational practice, one might expect a church to take steps to remedy the matter. But in ministering to ministers we must be stirred by something much higher than a desire to preserve the church’s reputation. The supreme motivation must be love.

END