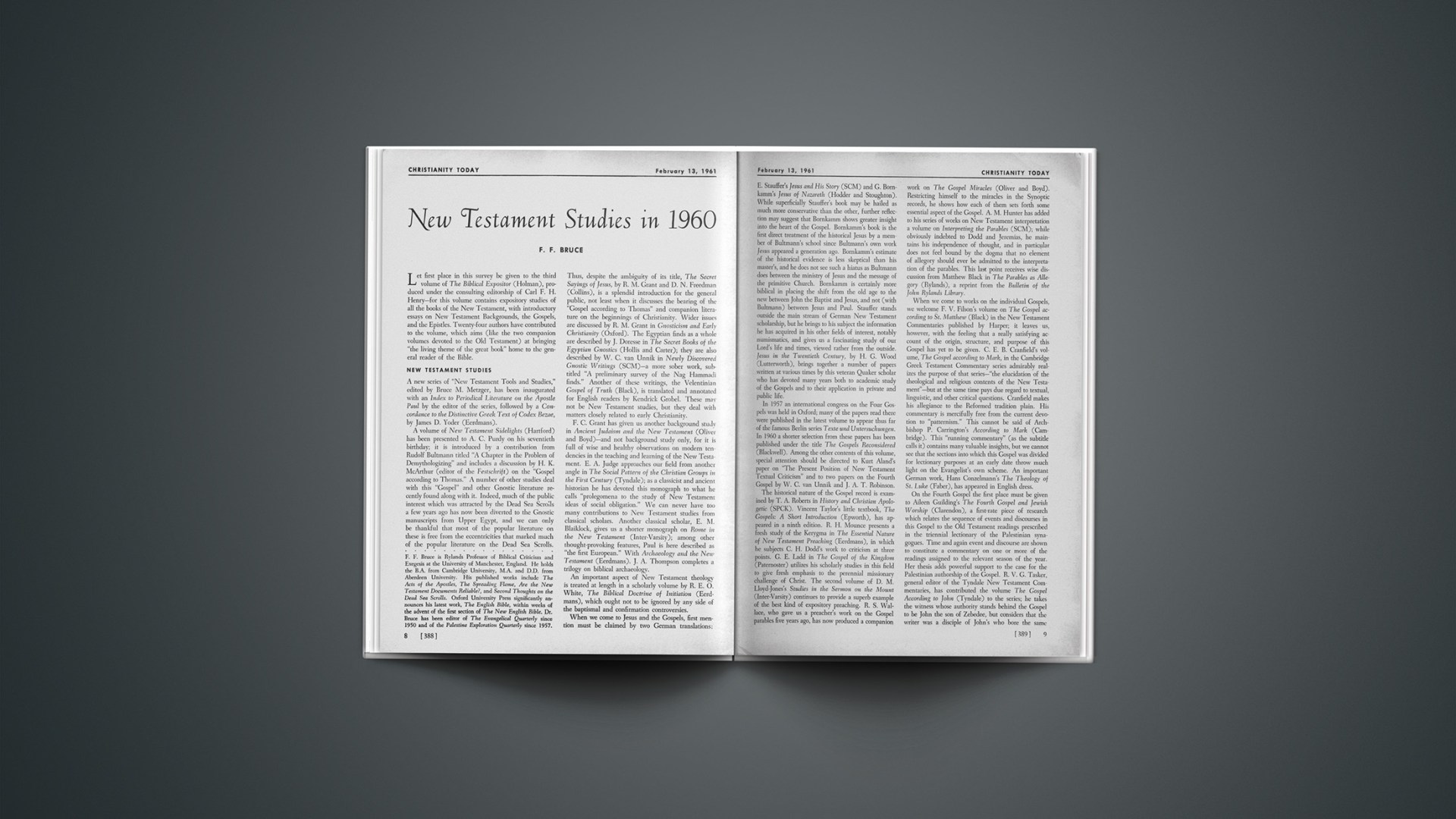

Let first place in this survey be given to the third volume of The Biblical Expositor (Holman), produced under the consulting editorship of Carl F. H. Henry—for this volume contains expository studies of all the books of the New Testament, with introductory essays on New Testament Backgrounds, the Gospels, and the Epistles. Twenty-four authors have contributed to the volume, which aims (like the two companion volumes devoted to the Old Testament) at bringing “the living theme of the great book” home to the general reader of the Bible.

NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES

A new series of “New Testament Tools and Studies,” edited by Bruce M. Metzger, has been inaugurated with an Index to Periodical Literature on the Apostle Paul by the editor of the series, followed by a Concordance to the Distinctive Greek Text of Codex Bezae, by James D. Yoder (Eerdmans).

A volume of New Testament Sidelights (Hartford) has been presented to A. C. Purdy on his seventieth birthday; it is introduced by a contribution from Rudolf Bultmann titled “A Chapter in the Problem of Demythologizing” and includes a discussion by H. K. McArthur (editor of the Festschrift) on the “Gospel according to Thomas.” A number of other studies deal with this “Gospel” and other Gnostic literature recently found along with it. Indeed, much of the public interest which was attracted by the Dead Sea Scrolls a few years ago has now been diverted to the Gnostic manuscripts from Upper Egypt, and we can only be thankful that most of the popular literature on these is free from the eccentricities that marked much of the popular literature on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Thus, despite the ambiguity of its title, The Secret Sayings of Jesus, by R. M. Grant and D. N. Freedman (Collins), is a splendid introduction for the general public, not least when it discusses the bearing of the “Gospel according to Thomas” and companion literature on the beginnings of Christianity. Wider issues are discussed by R. M. Grant in Gnosticism and Early Christianity (Oxford). The Egyptian finds as a whole are described by J. Doresse in The Secret Books of the Egyptian Gnostics (Hollis and Carter); they are also described by W. C. van Unnik in Newly Discovered Gnostic Writings (SCM)—a more sober work, subtitled “A preliminary survey of the Nag Hammadi finds.” Another of these writings, the Velentinian Gospel of Truth (Black), is translated and annotated for English readers by Kendrick Grobel. These may not be New Testament studies, but they deal with matters closely related to early Christianity.

F. C. Grant has given us another background study in Ancient Judaism and the New Testament (Oliver and Boyd)—and not background study only, for it is full of wise and healthy observations on modern tendencies in the teaching and learning of the New Testament. E. A. Judge approaches our field from another angle in The Social Pattern of the Christian Groups in the First Century (Tyndale); as a classicist and ancient historian he has devoted this monograph to what he calls “prolegomena to the study of New Testament ideas of social obligation.” We can never have too many contributions to New Testament studies from classical scholars. Another classical scholar, E. M. Blaiklock, gives us a shorter monograph on Rome in the New Testament (Inter-Varsity); among other thought-provoking features, Paul is here described as “the first European.” With Archaeology and the New Testament (Eerdmans). J. A. Thompson completes a trilogy on biblical archaeology.

An important aspect of New Testament theology is treated at length in a scholarly volume by R. E. O. White, The Biblical Doctrine of Initiation (Eerdmans), which ought not to be ignored by any side of the baptismal and confirmation controversies.

When we come to Jesus and the Gospels, first mention must be claimed by two German translations: E. Stauffer’s Jesus and His Story (SCM) and G. Bornkamm’s Jesus of Nazareth (Hodder and Stoughton). While superficially Stauffer’s book may be hailed as much more conservative than the other, further reflection may suggest that Bornkamm shows greater insight into the heart of the Gospel. Bornkamm’s book is the first direct treatment of the historical Jesus by a member of Bultmann’s school since Bultmann’s own work Jesus appeared a generation ago. Bornkamm’s estimate of the historical evidence is less skeptical than his master’s, and he does not see such a hiatus as Bultmann does between the ministry of Jesus and the message of the primitive Church. Bornkamm is certainly more biblical in placing the shift from the old age to the new between John the Baptist and Jesus, and not (with Bultmann) between Jesus and Paul. Stauffer stands outside the main stream of German New Testament scholarship, but he brings to his subject the information he has acquired in his other fields of interest, notably numismatics, and gives us a fascinating study of our Lord’s life and times, viewed rather from the outside. Jesus in the Twentieth Century, by H. G. Wood (Lutterworth), brings together a number of papers written at various times by this veteran Quaker scholar who has devoted many years both to academic study of the Gospels and to their application in private and public life.

In 1957 an international congress on the Four Gospels was held in Oxford; many of the papers read there were published in the latest volume to appear thus far of the famous Berlin series Texte und Untersuchungen. In 1960 a shorter selection from these papers has been published under the title The Gospels Reconsidered (Blackwell). Among the other contents of this volume, special attention should be directed to Kurt Aland’s paper on “The Present Position of New Testament Textual Criticism” and to two papers on the Fourth Gospel by W. C. van Unnik and J. A. T. Robinson.

The historical nature of the Gospel record is examined by T. A. Roberts in History and Christian Apologetic (SPCK). Vincent Taylor’s little textbook, The Gospels: A Short Introduction (Epworth), has appeared in a ninth edition. R. H. Mounce presents a fresh study of the Kerygma in The Essential Nature of New Testament Preaching (Eerdmans), in which he subjects C. H. Dodd’s work to criticism at three points. G. E. Ladd in The Gospel of the Kingdom (Paternoster) utilizes his scholarly studies in this field to give fresh emphasis to the perennial missionary challenge of Christ. The second volume of D. M. Lloyd-Jones’s Studies in the Sermon on the Mount (Inter-Varsity) continues to provide a superb example of the best kind of expository preaching. R. S. Wallace, who gave us a preacher’s work on the Gospel parables five years ago, has now produced a companion work on The Gospel Miracles (Oliver and Boyd). Restricting himself to the miracles in the Synoptic records, he shows how each of them sets forth some essential aspect of the Gospel. A. M. Hunter has added to his series of works on New Testament interpretation a volume on Interpreting the Parables (SCM); while obviously indebted to Dodd and Jeremias, he maintains his independence of thought, and in particular does not feel bound by the dogma that no element of allegory should ever be admitted to the interpretation of the parables. This last point receives wise discussion from Matthew Black in The Parables as Allegory (Rylands), a reprint from the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library.

When we come to works on the individual Gospels, we welcome F. V. Filson’s volume on The Gospel according to St. Matthew (Black) in the New Testament Commentaries published by Harper; it leaves us, however, with the feeling that a really satisfying account of the origin, structure, and purpose of this Gospel has yet to be given. C. E. B. Cranfield’s volume, The Gospel according to Mark, in the Cambridge Greek Testament Commentary series admirably realizes the purpose of that series—“the elucidation of the theological and religious contents of the New Testament”—but at the same time pays due regard to textual, linguistic, and other critical questions. Cranfield makes his allegiance to the Reformed tradition plain. His commentary is mercifully free from the current devotion to “patternism.” This cannot be said of Archbishop P. Carrington’s According to Mark (Cambridge). This “running commentary” (as the subtitle calls it) contains many valuable insights, but we cannot see that the sections into which this Gospel was divided for lectionary purposes at an early date throw much light on the Evangelist’s own scheme. An important German work, Hans Conzelmann’s The Theology of St. Luke (Faber), has appeared in English dress.

On the Fourth Gospel the first place must be given to Aileen Guilding’s The Fourth Gospel and Jewish Worship (Clarendon), a first-rate piece of research which relates the sequence of events and discourses in this Gospel to the Old Testament readings prescribed in the triennial lectionary of the Palestinian synagogues. Time and again event and discourse are shown to constitute a commentary on one or more of the readings assigned to the relevant season of the year. Her thesis adds powerful support to the case for the Palestinian authorship of the Gospel. R. V. G. Tasker, general editor of the Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, has contributed the volume The Gospel According to John (Tyndale) to the series; he takes the witness whose authority stands behind the Gospel to be John the son of Zebedee, but considers that the writer was a disciple of John’s who bore the same relation to him as Mark did to Peter. Walter Lüthi’s St. John’s Gospel (Oliver and Boyd) consists of expository sermons preached to his Basel congregation, “on the edge of the crater,” in the dark days between 1939 and 1942. M. F. Wiles in The Spiritual Gospel (Cambridge) has given us a study of the interpretation of the Fourth Gospel in the Early Church, especially in the commentaries by Theodore of Mopsuestia and Cyril of Alexandria. This study reminds us forcibly that no one can hope to comment adequately on this Gospel unless he is in sympathetic rapport with the mind of the Evangelist. This sympathy is evident in R. H. Lightfoot’s St. John’s Gospel: A Commentary (Oxford), first published in 1956 and now reissued in a new series of “Oxford Paperbacks.” A. J. B. Higgins reaches a high estimate of The Historicity of the Fourth Gospel (Lutterworth); he maintains its independence of the Synoptic tradition and its right to be regarded as a witness of at least equal authority. Leon Morris discusses The Dead Sea Scrolls and St. John’s Gospel (Westminster) in the twelfth Campbell Morgan Bible Lecture, and finds that a comparative study of the two leads to three conclusions: the uniqueness of Christianity, the Palestinian character of the Fourth Gospel, and the centrality of Christ. In a Tyndale monograph J. N. Birdsall examines The Bodmer Papyrus of the Gospel of John (Tyndale) and makes a notable contribution to textual criticism.

PAUL AND THE EPISTLES

Paul continues to attract the attention of Christian scholars. Paul: His Life and Work, by Walther von Loewenich (Oliver and Boyd), has been written in order to provide Christian readers with something which will help them to a better understanding of Paul; his approach is the classic Lutheran one. From the Roman Catholic side Alfred Wikenhauser has given us a study of Pauline Mysticism (Nelson), by which he means the experience of direct union between the believer and Christ. The reading of this book brings a fresh reminder of the increasing interaction between Protestant and Roman Catholic work in the field of biblical exegesis.

In last year’s survey it was noted that John Murray’s study of The Imputation of Adam’s Sin (Eerdmans) made one look forward all the more eagerly to the appearance of his commentary on Romans in the New International Commentary on the New Testament. The first volume of this commentary (covering Romans 1–8) has now been published, and our eager expectations are not disappointed. The Reformed school of Pauline exposition is worthily represented in our day by such a work as this. But we are brought to the very fountainhead of the Reformed School of Pauline exposition by the appearance in a new English translation of John Calvin’s commentary on First Corinthians. A series of expository addresses on I Corinthians has been made more widely available with the publication of The Royal Route to Heaven, by Alan Redpath (Pickering and Inglis).

The Tyndale New Testament Commentary on Philippians has been written by R. P. Martin. The same scholar pays more detailed attention to one passage in that Epistle in a Tyndale monograph titled An Early Christian Confession (Tyndale), a study of Philippians 2:5–11. He agrees with the common description of the passage as an early Christian hymn, but describes it further as an early Christian creed, characterized by an impressively high doctrine of the person and work of Christ, composed by Paul himself at an earlier date and incorporated by him in his letter to the Philippians. H. M. Carson has contributed the volume on Colossians and Philemon to the Tyndals series. He concludes that both Epistles were written from Rome, he deals satisfactorily with the problems of the Colossian heresy, and includes a useful section on the New Testament attitude to slavery.

In “The Authorship of the Pastorals” (The Evangelical Quarterly, July–September 1960) E. Earle Ellis gives a résumé and assessment of current trends. The “Torch” commentary on these Epistles, written by A. R. C. Leaney, continues to find in them genuine Pauline passages embedded in non-Pauline material.

The volume on Hebrews in the Tyndale series has been written by T. Hewitt. He acknowledges his indebtedness to William Manson’s work on this Epistle. On Hebrews 5:7 he has an unusual suggestion to make about our Lord’s prayer in Gethsemane, but it is not so new as he may think. The main lessons of the Epistle are lucidly and powerfully brought out. In Reading Through ‘Hebrews’ (Mowbrays) R. R. Williams, Bishop of Leicester, has published six lectures on the Epistle which he delivered from the episcopal throne in Leicester Cathedral during Lent 1959—a wholly admirable example of ex cathedra teaching.

Faith is the Victory, by E. M. Blaiklock (Paternoster) reproduces in book form a series of Bible readings in I John given at the Keswick Convention; the author’s classical scholarship is here put to good use in promoting the devotional application of the Epistle.

Lastly, we have two practical expositions of Revelation—The Apocalypse Today, by T. F. Torrance (Eerdmans), and Preaching from Revelation, by A. H. Baldinger (Zondervan). Both authors see clearly the Christocentric emphasis of the book, and communicate it to their public. Exposition like this, based on careful and scholarly exegesis, is a welcome change from the sensational nonsense that too often passes for exposition of Revelation.

Samuel M. Shoemaker is the author of a number of popular books and the gifted Rector of Calvary Episcopal Church in Pittsburgh. He is known for his effective leadership of laymen and his deeply spiritual approach to all vital issues.