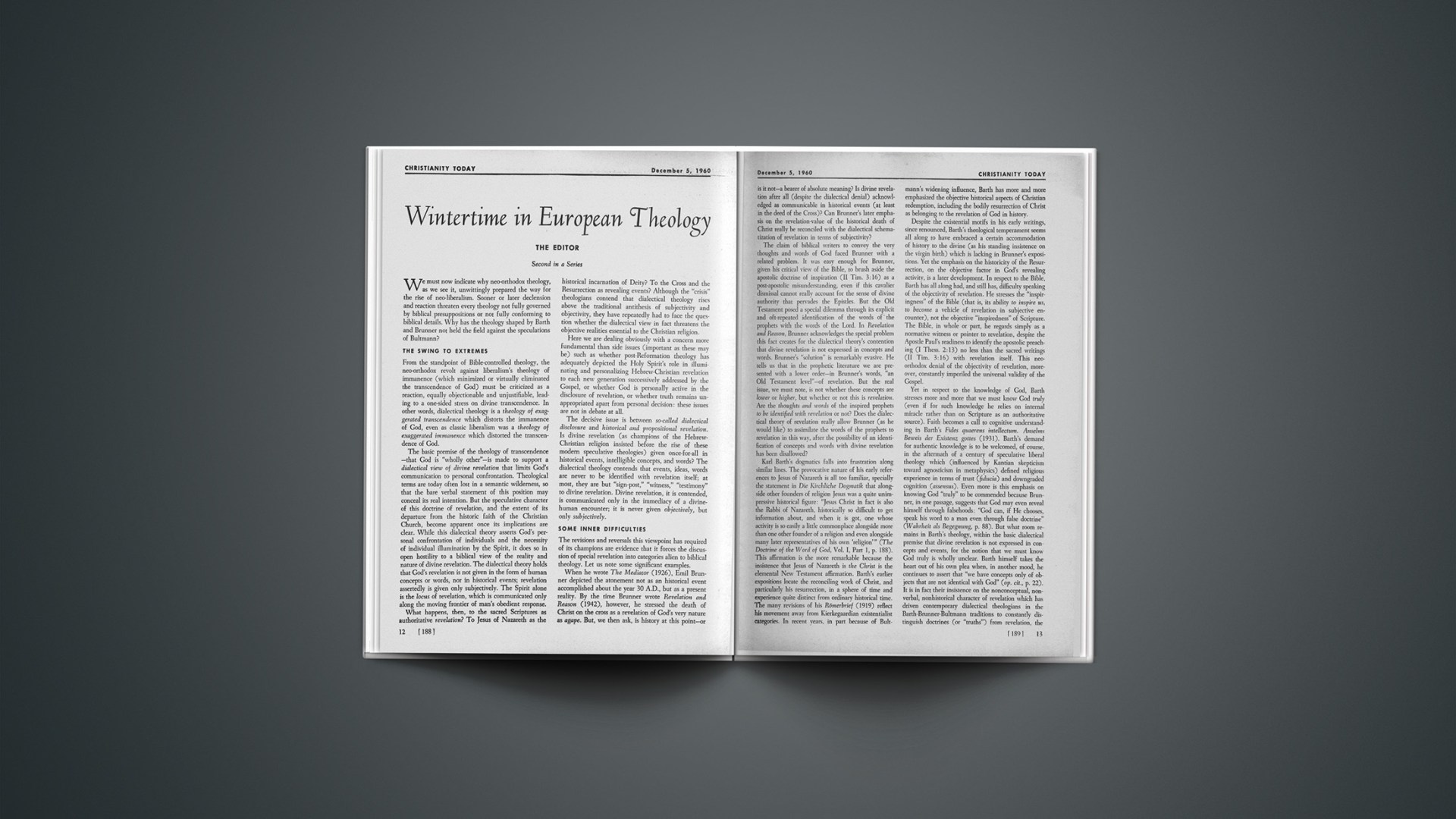

Second in a Series

We must now indicate why neo-orthodox theology, as we see it, unwittingly prepared the way for the rise of neo-liberalism. Sooner or later declension and reaction threaten every theology not fully governed by biblical presuppositions or not fully conforming to biblical details. Why has the theology shaped by Barth and Brunner not held the field against the speculations of Bultmann?

THE SWING TO EXTREMES

From the standpoint of Bible-controlled theology, the neo-orthodox revolt against liberalism’s theology of immanence (which minimized or virtually eliminated the transcendence of God) must be criticized as a reaction, equally objectionable and unjustifiable, leading to a one-sided stress on divine transcendence. In other words, dialectical theology is a theology of exaggerated transcendence which distorts the immanence of God, even as classic liberalism was a theology of exaggerated immanence which distorted the transcendence of God.

The basic premise of the theology of transcendence—that God is “wholly other”—is made to support a dialectical view of divine revelation that limits God’s communication to personal confrontation. Theological terms are today often lost in a semantic wilderness, so that the bare verbal statement of this position may conceal its real intention. But the speculative character of this doctrine of revelation, and the extent of its departure from the historic faith of the Christian Church, become apparent once its implications are clear. While this dialectical theory asserts God’s personal confrontation of individuals and the necessity of individual illumination by the Spirit, it does so in open hostility to a biblical view of the reality and nature of divine revelation. The dialectical theory holds that God’s revelation is not given in the form of human concepts or words, nor in historical events; revelation assertedly is given only subjectively. The Spirit alone is the locus of revelation, which is communicated only along the moving frontier of man’s obedient response.

What happens, then, to the sacred Scriptures as authoritative revelation? To Jesus of Nazareth as the historical incarnation of Deity? To the Cross and the Resurrection as revealing events? Although the “crisis” theologians contend that dialectical theology rises above the traditional antithesis of subjectivity and objectivity, they have repeatedly had to face the question whether the dialectical view in fact threatens the objective realities essential to the Christian religion.

Here we are dealing obviously with a concern more fundamental than side issues (important as these may be) such as whether post-Reformation theology has adequately depicted the Holy Spirit’s role in illuminating and personalizing Hebrew-Christian revelation to each new generation successively addressed by the Gospel, or whether God is personally active in the disclosure of revelation, or whether truth remains unappropriated apart from personal decision: these issues are not in debate at all.

The decisive issue is between so-called dialectical disclosure and historical and propositional revelation. Is divine revelation (as champions of the Hebrew-Christian religion insisted before the rise of these modern speculative theologies) given once-for-all in historical events, intelligible concepts, and words? The dialectical theology contends that events, ideas, words are never to be identified with revelation itself; at most, they are but “sign-post,” “witness,” “testimony” to divine revelation. Divine revelation, it is contended, is communicated only in the immediacy of a divine-human encounter; it is never given objectively, but only subjectively.

SOME INNER DIFFICULTIES

The revisions and reversals this viewpoint has required of its champions are evidence that it forces the discussion of special revelation into categories alien to biblical theology. Let us note some significant examples.

When he wrote The Mediator (1926), Emil Brunner depicted the atonement not as an historical event accomplished about the year 30 A.D., but as a present reality. By the time Brunner wrote Revelation and Reason (1942), however, he stressed the death of Christ on the cross as a revelation of God’s very nature as agape. But, we then ask, is history at this point—or is it not—a bearer of absolute meaning? Is divine revelation after all (despite the dialectical denial) acknowledged as communicable in historical events (at least in the deed of the Cross)? Can Brunner’s later emphasis on the revelation-value of the historical death of Christ really be reconciled with the dialectical schematization of revelation in terms of subjectivity?

The claim of biblical writers to convey the very thoughts and words of God faced Brunner with a related problem. It was easy enough for Brunner, given his critical view of the Bible, to brush aside the apostolic doctrine of inspiration (2 Tim. 3:16) as a post-apostolic misunderstanding, even if this cavalier dismissal cannot really account for the sense of divine authority that pervades the Epistles. But the Old Testament posed a special dilemma through its explicit and oft-repeated identification of the words of the prophets with the words of the Lord. In Revelation and Reason, Brunner acknowledges the special problem this fact creates for the dialectical theory’s contention that divine revelation is not expressed in concepts and words. Brunner’s “solution” is remarkably evasive. He tells us that in the prophetic literature we are presented with a lower order—in Brunner’s words, “an Old Testament level”—of revelation. But the real issue, we must note, is not whether these concepts are lower or higher, but whether or not this is revelation. Are the thoughts and words of the inspired prophets to be identified with revelation or not? Does the dialectical theory of revelation really allow Brunner (as he would like) to assimilate the words of the prophets to revelation in this way, after the possibility of an identification of concepts and words with divine revelation has been disallowed?

Karl Barth’s dogmatics falls into frustration along similar lines. The provocative nature of his early references to Jesus of Nazareth is all too familiar, specially the statement in Die Kirchliche Dogmatik that alongside other founders of religion Jesus was a quite unimpressive historical figure: “Jesus Christ in fact is also the Rabbi of Nazareth, historically so difficult to get information about, and when it is got, one whose activity is so easily a little commonplace alongside more than one other founder of a religion and even alongside many later representatives of his own ‘religion’ ” (The Doctrine of the Word of God, Vol. I, Part 1, p. 188). This affirmation is the more remarkable because the insistence that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ is the elemental New Testament affirmation. Barth’s earlier expositions locate the reconciling work of Christ, and particularly his resurrection, in a sphere of time and experience quite distinct from ordinary historical time. The many revisions of his Römerbrief (1919) reflect his movement away from Kierkegaardian existentialist categories. In recent years, in part because of Bultmann’s widening influence, Barth has more and more emphasized the objective historical aspects of Christian redemption, including the bodily resurrection of Christ as belonging to the revelation of God in history.

Despite the existential motifs in his early writings, since renounced, Barth’s theological temperament seems all along to have embraced a certain accommodation of history to the divine (as his standing insistence on the virgin birth) which is lacking in Brunner’s expositions. Yet the emphasis on the historicity of the Resurrection, on the objective factor in God’s revealing activity, is a later development. In respect to the Bible, Barth has all along had, and still has, difficulty speaking of the objectivity of revelation. He stresses the “inspiringness” of the Bible (that is, its ability to inspire us, to become a vehicle of revelation in subjective encounter), not the objective “inspiredness” of Scripture. The Bible, in whole or part, he regards simply as a normative witness or pointer to revelation, despite the Apostle Paul’s readiness to identify the apostolic preaching (1 Thess. 2:13) no less than the sacred writings (2 Tim. 3:16) with revelation itself. This neo-orthodox denial of the objectivity of revelation, moreover, constantly imperiled the universal validity of the Gospel.

Yet in respect to the knowledge of God, Barth stresses more and more that we must know God truly (even if for such knowledge he relies on internal miracle rather than on Scripture as an authoritative source). Faith becomes a call to cognitive understanding in Barth’s Fides quaerens intellectum. Anselms Beweis der Existenz gottes (1931). Barth’s demand for authentic knowledge is to be welcomed, of course, in the aftermath of a century of speculative liberal theology which (influenced by Kantian skepticism toward agnosticism in metaphysics) defined religious experience in terms of trust (fiducia) and downgraded cognition (assensus). Even more is this emphasis on knowing God “truly” to be commended because Brunner, in one passage, suggests that God may even reveal himself through falsehoods: “God can, if He chooses, speak his word to a man even through false doctrine” (Wahrheit als Begegnung, p. 88). But what room remains in Barth’s theology, within the basic dialectical premise that divine revelation is not expressed in concepts and events, for the notion that we must know God truly is wholly unclear. Barth himself takes the heart out of his own plea when, in another mood, he continues to assert that “we have concepts only of objects that are not identical with God” (op. cit., p. 22). It is in fact their insistence on the nonconceptual, nonverbal, nonhistorical character of revelation which has driven contemporary dialectical theologians in the Barth-Brunner-Bultmann traditions to constantly distinguish doctrines (or “truths”) from revelation, the Bible from revelation, and, for that matter, Jesus of Nazareth from “the Christ.”

The fact that Barth and Brunner compromise the basic dialectical premise at strategic points is to be explained only in this way: that the Judeo-Christian view itself makes demands which break through the narrow and artificial limits of the theological dialectical theory. The primary issue—really evaded by Barth and Brunner—is not whether in this point or that (historical event or concept or Bible declaration) we must somehow (even if inconsistently!) acknowledge the reality of divine revelation. The primary consideration rather is that this event, this knowledge, can be confidently identified with revelation only if we first reject the dialectical dogma that revelation is not communicated in concepts, words, or historical acts.

THE ROAD TO BULTMANN

Bultmann enters this controversy over the relation of revelation to history, science, and truth—over the connection of revelation with subjectivity or objectivity—by applying the basic dialectical premise itself in a more consistent and more devastating way.

Barth and Brunner had ambiguously related faith to science and to history no less than to reason. Brunner found it possible to say, on one side, that modern science cannot really touch the essence of Christian revelation, and, on the other, that “Orthodoxy has become impossible for anyone who knows anything of science. This I would call fortunate” (The Word and the World, p. 38). While the crisis-theologians have built a positive theological structure on the foundation of higher criticism, they have asserted that neither science nor history bisects the content of revelation. The implication is that whatever assaults scientific criticism and historical criticism may make on the Bible, they cannot in any manner really impair the content of the Gospel—because revelation assertedly is not communicated in the historico-scientific realm.

As already indicated, Barth and Brunner compromise the consistent application of this principle. In deference to certain strategic elements of the biblical witness, they “protect” the historical nature of the atonement (Brunner) and the resurrection of Christ (Barth); insist on authentic knowledge of the supernatural God (Barth); and even affirm a low-level revelation status for parts of the Bible (Brunner).

Bultmann wants none of this. He will not accommodate the dialectical philosophy to such core elements of Hebrew-Christian theology derived actually from a biblical (and non-dialectical) revelation situation. And Bultmann’s plea for a thorough and uncompromised application of the dialectical view of revelation has caught the fancy and imagination of young intellectuals in many German divinity schools.

Lost Christmas

Somewhere, buried under tissue,

Bent beneath the load

Of our hurried, harried giving,

Christmas lost the road.

Christmas, that was sweet and simple,

With a song, a star,

Christmas that was hushed and holy,

Seems so very far!

Let us stop and look for Christmas:

Maybe, if we tried,

We could find it somewhere under

All the gifts we tied.

Christmas waiting, wistful, weary,

May be very near—

Christmas lost, a little lonely,

Wishing to be here.

HELEN FRAZEE BOWER

Samuel M. Shoemaker is the author of a number of popular books and the gifted Rector of Calvary Episcopal Church in Pittsburgh. He is known for his effective leadership of laymen and his deeply spiritual approach to all vital issues.