At the beginning of World War II, it was often said in this country that the recurrence of a cosmic catastrophe of global dimensions had seriously shaken American belief in inevitable progress and that the days of naive optimism were gone for good. But since we of this nation had to bear far less of the brunt of the bloody holocaust than our European allies, we emerged from the terrible conflagration as the most prosperous of all peoples and experienced such an increase in political and military power that with the exception of Russia all the other nations have been reduced to second or third rank in international affairs. All these developments condition personal life in the States to such an extent that the horrors, losses, and privations of war have been almost forgotten.

The Mood Of Our Age

Our nation indulges in a mood of complacency and is obsessed by a passion to do things more quickly every day, to make them bigger every year, and to double one’s income every 10 years. Consequently, while belief in progress has subsided and people are rather skeptical about the perfectability of life in this world, we feel at least pretty secure in our position. We take for granted that in competition with Russia we will never lose our superiority; and in spite of what scientists say about the fatal consequences of the fall-out of atomic particles, we are certain that our country will escape any such serious harm should there be atomic war.

Sure enough, there is some discontent with our government as well as with some politicians, but such feeling is confined to relatively small areas of life. There is no general indignation—only griping and sniping. And the churches are in no way different. They, too, reflect the invigorating influence which the war effort has had on the life of the nation. A great deal has been done to increase church membership; new sanctuaries and Sunday School buildings have sprung up everywhere, the output of religious literature has reached an all-time high, and there are signs that the movement has lost momentum.

It was to people in a similar condition and mood that Paul wrote his letter to Ephesus. With patience he first points out to them the great love God has shown in delivering them from their former life. Then he reminds them of the riches they possess in Christ. Furthermore he admonishes them to live in unity together and in mutual regard. But as he reaches the end of his communication he can no longer refrain from warning them of the critical situation in which they find themselves. Far from being delivered of all dangers, they ought to be aware of terrific conflict, of being assailed from all sides by dangerous powers of a supranatural kind which can be overcome only when fought by the weapons of faith. Christians may, in spite of all the fine things of this world they enjoy, find themselves defeated in life because they fail to take up their spiritual arms and fight those powers.

Our first reaction to such a passage as this in Ephesians is to shrug it off. We tell ourselves that Paul not only spoke the language of his age but shared its ideas, and modern science has long overcome such supranaturalism. But is that not dodging the real problem? For it is obvious that in this passage Paul does not theoretically describe his world view. He speaks of practical things which require human action. No matter what kind of terminology he used, Paul was aware of powerful realities that threaten man’s life and which, if left unheeded, are apt to destroy not only his faith but undo his redemption. The complacency and sentiment of security characterizing our age are indicative of our spiritual outlook—our conviction that there is nothing seriously wrong with the world. Whatever evils may befall us in any sphere of life, we are confident that they will not affect us too deeply. With the abundance of resources at our disposal, plus scientific knowledge, we believe every evil in this world can be brought under human control. To many people self-assurance on the part of modern man is evidence of the great progress he has made since primitive days when fear haunted him all the time. To us, however, this development is disquieting, for it associates itself with ease in biblical faith as well as sheer unbelief. We are so capable of deluding ourselves that we fail to recognize the cleavage between our attitude and the biblical formulations to which we pay lip service. Except for rare instances, as in foxholes, we do not need God because things in modern life take care of themselves.

This entire attitude is reflected in theology. What makes religious existentialism so attractive to our generation is the notion that man is capable, by act of existential self-assertion, to straighten out his life. Yet this same attitude underlies “beggar Protestantism” in which God is considered the never failing, inexhaustible source of good gifts. In that attitude man both underrates the power of evil and overrates his own significance. In either type God is thought of as being at man’s disposal. The sway scientific thought holds over our lives is undoubtedly one reason for this transformation of Christian religion into humanism. The Bible does not give an explanation of the origin of evil in this world. Rather it leaves us with a few hints and points to the experience of the various evils. But our age has become distrustful of experience, which on account of its subjective character seems to be unreliable, whereas explanations sound like logical facts deserving full acceptance. The amazing results of modern science rest upon the basic axiom that this is a world of order, regularity, and balance. Since this axiom works so successfully, it would seem to claim our unreserved recognition. But the fallacy of such reasoning is obvious when we realize that human life is the will to work according to purpose, whereas a purely casual view of science ignores completely the teleological character of life.

What makes life confusing despite the general rule of natural laws is the fact that every living creature pursues ends, but no general harmony of ends in this world exists. There is, for example, nothing wrong with the presence of certain germs. But when they settle or operate in the wrong place—my respiratory system or my stomach, for instance—then my body resents them. Similarly it is a wonderful thing that I can use nature’s energies for moving my car and bringing me to certain places. This movement depends on the cooperation of kinetic energy laws, combustion, and gravitation. But in the teleological process of driving a car, so many factors are coordinated that failure of even a small part may result in my car’s moving in the wrong direction. It is from such general considerations of the teleological nature of life that we must understand what the Bible has to say about evil and its operation.

In turning to the Scriptures, one is struck first of all by the soberness with which they judge human life. Ruthlessly they unmask the illusion that the value of life depends on how we feel about it. The rich man or the powerful ruler may enjoy the superiority of their status but that does not make their life meaningful. At the same time the person who has obeyed God’s commandments all along may be despondent because he sees the powers of wickedness or unbelief triumph. Nevertheless he is told not to become dejected; God will take care of his people.

Our Predicament

Two things are particularly emphasized in the Bible with reference to man’s predicament. First, this is a world in which man is lost apart from God. Secondly, man is confronted by antiteleological forces against which he is impotent. None of us as modern men are inclined to admit our lostness in this world. But the frantic way in which we express our belief in the natural or intrinsic meaning of life is clear indication of the insecurity that gnaws at our hearts. If life were indeed so positively valuable, as we tell ourselves it is, why do we not simply enjoy it? We know in the depths of our hearts that life falls far short of giving true satisfaction. See, for instance, how much our age is willing to pay for ways and means of killing time. We carry our money to the movie or the theater, we spend hours each day reading newspapers and magazines, we sit before a TV set and accept a lot of nonsense and trash that comes to us, or we go to a stadium to watch others play.

Take our sense of futility. While it may be an exaggeration to say that anxiety is the disease of modern mankind, it can hardly be denied that modern man thinks his life is empty. If proof were needed for this, our country’s consumption of alcoholic beverages would furnish it. People need this stimulus because their daily lives have dulled their minds. Many feel unable to start a conversation without a cocktail. But one has only to read liquor advertisements in our magazines to realize that alcohol is not fit to give content to life. It only serves to make people forget that they do not have what is worth sharing.

The trying emptiness of human life is not a modern discovery. Man’s situation has not really changed since the days of the Old Testament prophets. But the biblical writers were men who could not be deluded by the activism and apparent happiness of their contemporaries. We, on the other hand, are so uncertain of ourselves that we refrain from questioning even the meaning of pastime.

No matter how capable we are of forcing nature to subservience to our purposes, we are not able to impart meaning to our lives. Modern man who worships success surmises that the successful man can subject the forces of nature and fate to himself. But the Bible reminds us that even in the most favorable cases success lasts only for a few decades. In death we lose complete control of all the things that were ours.

Whenever people realize that this is the normal course of human affairs—and very few are entirely blind to this fact—they try to comfort themselves in the notion that things will eventually be better or easier for their children. But why should that be the case? Jesus reminds us that every generation has its own evilness or burden, and that the years have not improved so far as basic conditions of human life are concerned. While the nature of many problems may change from age to age and place to place, the heavy weight of them remains the same. Life requires less manual work than it did a generation ago, but our machines and appliances have proven to be exacting tyrants. Is it not paradoxical that modern man, who saves so much time because he has a telephone, a car, an airplane, and duplicating machinery at his disposal, has in fact less time than his grandfather and probably worries as much? Behind this sense of emptiness and anxiety there lurks the feeling that our many activities do not make life meaningful either. We desire to work because we want to forget and because work seems to offer the evidence of accomplishing something. But the Geneva conference on atomic disarmament revealed to us the enslavement man has brought upon himself by his own works.

Our Impotence

The Bible does not leave us in doubt as to why human life is ultimately futile and hopeless. It tells us that the world, the devil, and sin are the causes of our unsatisfactory predicament. The world in which we live is a rather intriguing place to live in. Usually we act as though its things were the neutral raw material which man could use at his own discretion. And modern technology has seemed to be the most flattering to man’s ingenuity. But as accidents and modern diseases show, the works of our hands are rebellious servants, and for every movement forward there is a price. Foolish it would be to think that man’s inventions could eventually render him happier. The law of equalization is one of the basic laws of this world, and every human invention will be used for evil as well as good purposes. To confine the use of atomic energy to peaceful purposes, or prevent wicked people from using cars and airplanes for criminal ends, or to preclude the dissemination of falsehood through the media of mass communication would be impossible.

However, the worst feature about this world is its relative harmony, the fact that great things can be accomplished in it, and that man is offered an abundance of things to enjoy. Because of this very condition, one gets the impression that the world is an end in itself, sufficient to produce all that man needs or wants. Herein is man fatally deceived. Satisfied with the world’s resources and opportunities, man overlooks or denies completely the work of the Creator, and accordingly considers himself the master of this world. Is it not he who in his wisdom has succeeded in discovering all its secrets and by the power of his will has transformed the raw materials of nature into the work of his hands? It is on account of this deceptiveness of the world that we are told in the New Testament to make use of the world as God created it, but not to love it.

Experience in the world shows how right the Bible is in its estimate of the powers of evil. Things are not evil in themselves, yet in spite of intrinsic goodness they can be made to bring about baneful results. The Old Testament gives expression to the experience of the world’s unreliability and insufficiency, while the New Testament points out in many places why it is that the world, originally good, should be so uncooperative with man in his aspirations for a meaningful life. This world is not truly itself because it is controlled by the devil. Such a belief, of course, appears repulsive to our age. Yet Jesus himself spoke of it without reservation and without giving the slightest hint that this was an accommodation to popular belief or a façon de parler. One cannot dismiss the powers of evil as antiquated superstitions. The question is not how we should therefore represent the devil and the forces of evil, but rather, how we are to react to their activity in this world.

The answer to the problem lies in accepting first the fact of evil in this world. It is not on account of wrong ideas of reality, as Christian Science says, that we think we encounter evils. Rather, the very fact that we are capable of illusions and delusions is itself an indication that were we to make every effort possible we would not be able to escape the evils in this world. Secondly, belief in evil implies that evils in nature have to be taken no less seriously than those in man’s mental life. All through this world we find the clash of teleologies and conflict. Thirdly, the full gravity of the operation of evil is to be found in the spiritual realm. It is not by chance that our aspirations and desires are so frequently obstructed. Behind experience we note a deliberate will in us by which we are tempted to turn away from God. This experience compels us to enlarge our notion of evil. In our naivete, we are prone to call evil that which obviates our desire for happiness and health or that which is contrary to moral commandments. But Jesus pointed out that everything in this world—health, happiness, beauty, wealth, peaceful conditions, even goodness and religion—may be used against us. None of these things are evil in themselves; but all of them, useful and pleasing as they may be in some respects, can be used to our spiritual detriment through the forces of evil. We can therefore say that everything endangering our divine destination is evil, and accordingly we must admit that we do not have the spiritual strength to resist it permanently and effectively. Forces of evil are actually in control of our lives.

Our Redemption

If we take seriously all that the Bible says about the human predicament, we shall hardly be inclined to cling to the optimistic view of life that comes so naturally to us. Yet it would be unfortunate to interpret the biblical view of evil in terms of thoroughgoing pessimism. While these facts, once they are shown to us, cannot be denied, it is understandable that man is by nature unprepared to embrace such a gloomy view. Only in the light of Christ’s redemptive work can we become fully aware of the dark features of this world and their power, for it is from them that he brings redemption to us. Through him the world and the devil have been overcome.

While the remission of sins is not due to man’s moral or religious efforts but is rather a gift of divine grace, justification and redemption are not mere legal fictions as some theologians have held. On account of our sins we live in a world of evils; and so in consequence to the remission of our sins (as evidence of their reality) we are delivered from them. Right therefore is the proclamation ‘Good News,’ of which the work of Jesus is called. Though those who follow Jesus will not be spared calamities in this world, their lives no longer share the futility of the rest of human lives. For with Jesus the power of God (the ‘Kingdom’) has become an active factor in history. We live already in a sphere where the antiteleological forces are counteracted. What this means Paul makes plain in the concluding section of Romans 8. While one could hardly ask for a more exhaustive list than Paul’s of the evils to which we are exposed, the Apostle nevertheless exclaims confidently that in all these afflictions we win an overwhelming victory on account of Him who loved us! Conquest of the forces of evil commenced with Jesus’ victory over temptation, sin, and death, and it continues until all of God’s foes have been overcome in the Lord’s Return. This is the glory and depth of the Christian life as contrasted with what our contemporaries call ‘having a good life.’ We take the evils of this world seriously, as evidences of God’s anger, but we place all weight upon the fact that Christ’s love transforms them into opportunities for patient acceptance of our divine education and for compassion on our fellow men.

END

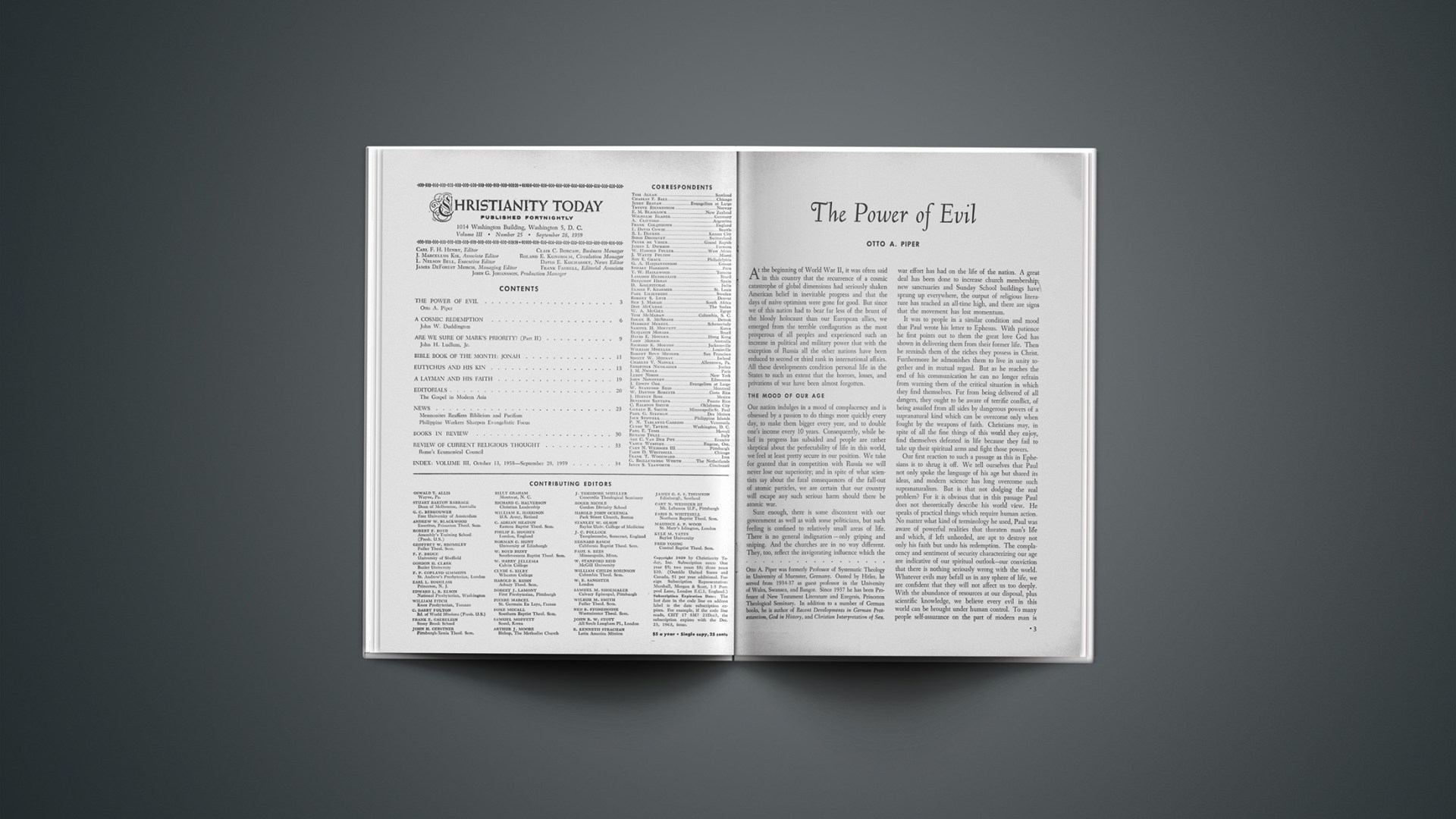

Otto A. Piper was formerly Professor of Systematic Theology in University of Muenster, Germany. Ousted by Hitler, he served from 1934–37 as guest professor in the University of Wales, Swansea, and Bangor. Since 1937 he has been Professor of New Testament Literature and Exegesis, Princeton Theological Seminary. In addition to a number of German books, he is author of Recent Developments in German Protestantism, God in History, and Christian Interpretation of Sex.