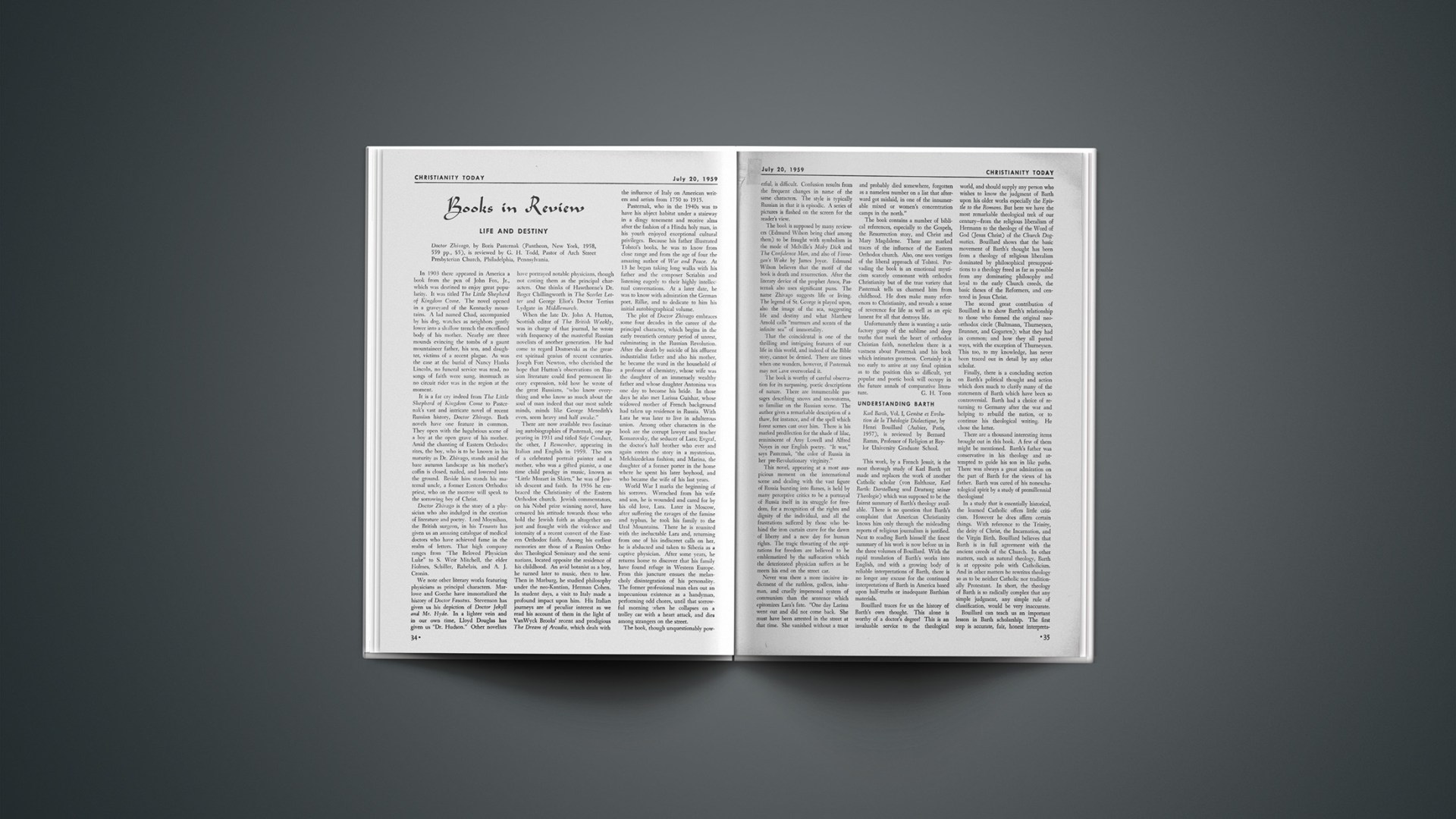

Life And Destiny

Doctor Zhivago, by Boris Pasternak (Pantheon, New York, 1958, 559 pp., $5), is reviewed by G. H. Todd, Pastor of Arch Street Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In 1903 there appeared in America a book from the pen of John Fox, Jr., which was destined to enjoy great popularity. It was titled The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come. The novel opened in a graveyard of the Kentucky mountains. A lad named Chad, accompanied by his dog, watches as neighbors gently lower into a shallow trench the encoffined body of his mother. Nearby are three mounds evincing the tombs of a gaunt mountaineer father, his son, and daughter, victims of a recent plague. As was the case at the burial of Nancy Hanks Lincoln, no funeral service was read, no songs of faith were sung, inasmuch as no circuit rider was in the region at the moment.

It is a far cry indeed from The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come to Pasternak’s vast and intricate novel of recent Russian history, Doctor Zhivago. Both novels have one feature in common. They open with the lugubrious scene of a boy at the open grave of his mother. Amid the chanting of Eastern Orthodox rites, the boy, who is to be known in his maturity as Dr. Zhivago, stands amid the bare autumn landscape as his mother’s coffin is closed, nailed, and lowered into the ground. Beside him stands his maternal uncle, a former Eastern Orthodox priest, who on the morrow will speak to the sorrowing boy of Christ.

Doctor Zhivago is the story of a physician who also indulged in the creation of literature and poetry. Lord Moynihan, the British surgeon, in his Truants has given us an amazing catalogue of medical doctors who have achieved fame in the realm of letters. That high company ranges from “The Beloved Physician Luke” to S. Weir Mitchell, the elder Holmes, Schiller, Rabelais, and A. J. Cronin.

We note other literary works featuring physicians as principal characters. Marlowe and Goethe have immortalized the history of Doctor Faustus. Stevenson has given us his depiction of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In a lighter vein and in our own time, Lloyd Douglas has given us “Dr. Hudson.” Other novelists have portrayed notable physicians, though not casting them as the principal characters. One thinks of Hawthorne’s Dr. Roger Chillingworth in The Scarlet Letter and George Eliot’s Doctor Tertius Lydgate in Middlemarch.

When the late Dr. John A. Hutton, Scottish editor of The British Weekly, was in charge of that journal, he wrote with frequency of the masterful Russian novelists of another generation. He had come to regard Dostoevski as the greatest spiritual genius of recent centuries. Joseph Fort Newton, who cherished the hope that Hutton’s observations on Russian literature could find permanent literary expression, told how he wrote of the great Russians, “who know everything and who know so much about the soul of man indeed that our most subtle minds, minds like George Meredith’s even, seem heavy and half awake.”

There are now available two fascinating autobiographies of Pasternak, one appearing in 1931 and titled Safe Conduct, the other, I Remember, appearing in Italian and English in 1959. The son of a celebrated portrait painter and a mother, who was a gifted pianist, a one time child prodigy in music, known as “Little Mozart in Skirts,” he was of Jewish descent and faith. In 1936 he embraced the Christianity of the Eastern Orthodox church. Jewish commentators, on his Nobel prize winning novel, have censured his attitude towards those who hold the Jewish faith as altogether unjust and fraught with the violence and intensity of a recent convert of the Eastern Orthodox faith. Among his earliest memories are those of a Russian Orthodox Theological Seminary and the seminarians, located opposite the residence of his childhood. An avid botanist as a boy, he turned later to music, then to law. Then in Marburg, he studied philosophy under the neo-Kantian, Herman Cohen. In student days, a visit to Italy made a profound impact upon him. His Italian journeys are of peculiar interest as we read his account of them in the light of VanWyck Brooks’ recent and prodigious The Dream of Arcadia, which deals with the influence of Italy on American writers and artists from 1750 to 1915.

Pasternak, who in the 1940s was to have his abject habitat under a stairway in a dingy tenement and receive alms after the fashion of a Hindu holy man, in his youth enjoyed exceptional cultural privileges. Because his father illustrated Tolstoi’s books, he was to know from close range and from the age of four the amazing author of War and Peace. At 13 he began taking long walks with his father and the composer Scriabin and listening eagerly to their highly intellectual conversations. At a later date, he was to know with admiration the German poet, Rilke, and to dedicate to him his initial autobiographical volume.

The plot of Doctor Zhivago embraces some four decades in the career of the principal character, which begins in the early twentieth century period of unrest, culminating in the Russian Revolution. After the death by suicide of his affluent industrialist father and also his mother, he became the ward in the household of a professor of chemistry, whose wife was the daughter of an immensely wealthy father and whose daughter Antonina was one day to become his bride. In those days he also met Larissa Guishar, whose widowed mother of French background had taken up residence in Russia. With Lara he was later to live in adulterous union. Among other characters in the book are the corrupt lawyer and teacher Komarovsky, the seducer of Lara; Evgraf, the doctor’s half brother who ever and again enters the story in a mysterious, Melchizedekan fashion; and Marina, the daughter of a former porter in the home where he spent his later boyhood, and who became the wife of his last years.

World War I marks the beginning of his sorrows. Wrenched from his wife and son, he is wounded and cared for by his old love, Lara. Later in Moscow, after suffering the ravages of the famine and typhus, he took his family to the Ural Mountains. There he is reunited with the ineluctable Lara and, returning from one of his indiscreet calls on her, he is abducted and taken to Siberia as a captive physician. After some years, he returns home to discover that his family have found refuge in Western Europe. From this juncture ensues the melancholy disintegration of his personality. The former professional man ekes out an impecunious existence as a handyman, performing odd chores, until that sorrowful morning when he collapses on a trolley car with a heart attack, and dies among strangers on the street.

The book, though unquestionably powerful, is difficult. Confusion results from the frequent changes in name of the same characters. The style is typically Russian in that it is episodic. A series of pictures is flashed on the screen for the reader’s view.

The book is supposed by many reviewers (Edmund Wilson being chief among them) to be fraught with symbolism in the mode of Melville’s Moby Dick and The Confidence Man, and also of Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce. Edmund Wilson believes that the motif of the book is death and resurrection. After the literary device of the prophet Amos, Pasternak also uses significant puns. The name Zhivago suggests life or living. The legend of St. George is played upon, also the image of the sea, suggesting life and destiny and what Matthew Arnold calls “murmurs and scents of the infinite sea” of immortality.

That the coincidental is one of the thrilling and intriguing features of our life in this world, and indeed of the Bible story, cannot be denied. There are times when one wonders, however, if Pasternak may not Lave overworked it.

The book is worthy of careful observation for its surpassing, poetic descriptions of nature. There are innumerable passages describing snows and snowstorms, so familiar on the Russian scene. The author gives a remarkable description of a thaw, for instance, and of the spell which forest scenes cast over him. There is his marked predilection for the shade of lilac, reminiscent of Amy Lowell and Alfred Noyes in our English poetry. “It was,” says Pasternak, “the color of Russia in her pre-Revolutionary virginity.”

This novel, appearing at a most auspicious moment on the international scene and dealing with the vast figure of Russia bursting into flames, is held by many perceptive critics to be a portrayal of Russia itself in its struggle for freedom, for a recognition of the rights and dignity of the individual, and all the frustrations suffered by those who behind the iron curtain crave for the dawn of liberty and a new day for human rights. The tragic thwarting of the aspirations for freedom are believed to be emblematized by the suffocation which the deteriorated physician suffers as he meets his end on the street car.

Never was there a more incisive indictment of the ruthless, godless, inhuman, and cruelly impersonal system of communism than the sentence which epitomizes Lara’s fate. “One day Larissa went out and did not come back. She must have been arrested in the street at that time. She vanished without a trace and probably died somewhere, forgotten as a nameless number on a list that afterward got mislaid, in one of the innumerable mixed or women’s concentration camps in the north.”

The book contains a number of biblical references, especially to the Gospels, the Resurrection story, and Christ and Mary Magdalene. There are marked traces of the influence of the Eastern Orthodox church. Also, one sees vestiges of the liberal approach of Tolstoi. Pervading the book is an emotional mysticism scarcely consonant with orthodox Christianity but of the true variety that Pasternak tells us charmed him from childhood. He does make many references to Christianity, and reveals a sense of reverence for life as well as an epic lament for all that destroys life.

Unfortunately there is wanting a satisfactory grasp of the sublime and deep truths that mark the heart of orthodox Christian faith, nonetheless there is a vastness about Pasternak and his book which intimates greatness. Certainly it is too early to arrive at any final opinion as to the position this so difficult, yet popular and poetic book will occupy in the future annals of comparative literature.

G. H. TODD

Understanding Barth

Karl Barth, Vol. I, Genèse et Evolution de la Théologie Dialectique, by Henri Bouillard (Aubier, Paris, 1957), is reviewed by Bernard Ramm, Professor of Religion at Baylor University Graduate School.

This work, by a French Jesuit, is the most thorough study of Karl Barth yet made and replaces the work of another Catholic scholar (von Balthasar, Karl Barth: Darstellung und Deutung seiner Theologie) which was supposed to be the fairest summary of Barth’s theology available. There is no question that Barth’s complaint that American Christianity knows him only through the misleading reports of religious journalism is justified. Next to reading Barth himself the finest summary of his work is now before us in the three volumes of Bouillard. With the rapid translation of Barth’s works into English, and with a growing body of reliable interpretations of Barth, there is no longer any excuse for the continued interpretations of Barth in America based upon half-truths or inadequate Barthian materials.

Bouillard traces for us the history of Barth’s own thought. This alone is worthy of a doctor’s degree! This is an invaluable service to the theological world, and should supply any person who wishes to know the judgment of Barth upon his older works especially the Epistle to the Romans. But here we have the most remarkable theological trek of our century—from the religious liberalism of Hermann to the theology of the Word of God (Jesus Christ) of the Church Dogmatics. Bouillard shows that the basic movement of Barth’s thought has been from a theology of religious liberalism dominated by philosophical presuppositions to a theology freed as far as possible from any dominating philosophy and loyal to the early Church creeds, the basic theses of the Reformers, and centered in Jesus Christ.

The second great contribution of Bouillard is to show Barth’s relationship to those who formed the original neo-orthodox circle (Bultmann, Thurneysen, Brunner, and Gogarten); what they had in common; and how they all parted ways, with the exception of Thurneysen. This too, to my knowledge, has never been traced out in detail by any other scholar.

Finally, there is a concluding section on Barth’s political thought and action which does much to clarify many of the statements of Barth which have been so controversial. Barth had a choice of returning to Germany after the war and helping to rebuild the nation, or to continue his theological writing. He chose the latter.

There are a thousand interesting items brought out in this book. A few of them might be mentioned. Barth’s father was conservative in his theology and attempted to guide his son in like paths. There was always a great admiration on the part of Barth for the views of his father. Barth was cured of his noneschatological spirit by a study of premillennial theologians!

In a study that is essentially historical, the learned Catholic offers little criticism. However he does affirm certain things. With reference to the Trinity, the deity of Christ, the Incarnation, and the Virgin Birth, Bouillard believes that Barth is in full agreement with the ancient creeds of the Church. In other matters, such as natural theology, Barth is at opposite pole with Catholicism. And in other matters he rewrites theology so as to be neither Catholic nor traditionally Protestant. In short, the theology of Barth is so radically complex that any simple judgment, any simple rule of classification, would be very inaccurate.

Bouillard can teach us an important lesson in Barth scholarship. The first step is accurate, fair, honest interpretation. Prior to a “hard stand” or a “soft stand” on Barth is a competent, fair, scholarly interpretation of Barth. After we have done this then we are free to bring all the force of our critical judgment to bear. Bouillard, a Jesuit, has given us a classic example of the first step.

BERNARD RAMM

Fascinating And Cozy

20 Centuries of Christianity, by Paul Hutchinson and Winfred E. Garrison (Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1959, 306 pp., $6), is reviewed by Paul Woolley, Professor of Church History, Westminster Theological Seminary.

There is at last a buyers’ market in general church histories. Within this year there has been a revised edition of Walker, a new paper-back by Martin E. Marty, and the volume here under review. They are not duplicates of one another in any sense. Rather, they are three different types of history for three different interests, tastes, and stages of knowledge.

The present book is a fascinating story for the amateur, the tyro, who has little or no background in this field. It is best that the reader be one who likes to have his conclusions presented to him by the author. He should be a man who does not want to think too hard or face too many puzzling problems. Here he will find the answers without having to hunt for them.

The present book is really two in one. The first eight chapters, written by Paul Hutchinson, late editor of The Christian Century, have a warm, rather diffuse style that reads easily. One learns many things, does not get particularly excited about anything, and feels very cozy about the whole business. Big issues are neatly sidestepped. “Human nature is a pretty constant quality, and those who deplore the divisions among Christians today should at least remember that there have been disagreements within the Christian community from the beginning” (p 24). A life of Jesus cannot be written (p. 5). “His followers believed that he rose from the dead” (p. 6). One is not invited to pause and discover whether he actually did or not.

The other 18 chapters (covering the ground from the fourth century to the present) are by Winfred E. Garrison, Professor Emeritus of Church History at the University of Chicago. Here the outlines become sharper, the pulse quickens, and the air is not so warm and sticky. The author knows what he thinks about a subject and lets the reader in on his opinions. Garrison has the ability to contrast a fact with a legend and still give you the privilege of hearing the latter and enjoying any incidental instruction there may be in it.

He has certain opinions about the course of history that are stimulating. The modern world springs largely from the influence of the Renaissance. There were a great many critics of the church beside the Reformers, but the latter thought they should do something about it instead of being armchair critics. The Reformation was not a movement which divided; it was four separate movements which never united. The Reformers believed in biblical infallibility, but we are beyond that stage. There is a warm appreciation of pietism and its contributions to the modern development of the church.

The book is a bit careless about facts in spots. For instance, Servetus was condemned by a Roman Catholic court in France, not Spain. But there is nothing extremely important in these few errors.

Most useful is the clarity with which the dangers that stem from the political claims of the Roman church are outlined.

The chief disappointment of the book is the nebulous character of the Christianity that is summed up in the concluding chapter. The reader is assured that Christianity will survive because it is the only sufficient answer to man’s spiritual need. For that and other reasons it will assuredly survive. But what survives must have much more content, must provide a lot more meat and backbone than can be discovered in this last chapter or indeed in the thrust of the book as a whole. If there were not more to Christianity than the authors tell us about, it would not even be surviving now.

PAUL WOOLLEY

One Aspect Of God

Spirit, Son and Father, by Henry P. Van Dusen (Scribners, 1958, 180 pp., $3.50), is reviewed by Edwin H. Palmer, author of The Holy Spirit.

In this book Dr. Van Dusen, president of Union Theological Seminary, sets forth clearly his interpretation of the term Holy Spirit. Whether one agrees with his concepts or not, at least one must recognize that he has performed a service in presenting in lucid fashion this school of thought that reinterprets the classical, historical Christian position on the Holy Spirit.

This is a reinterpretation. According to the author, the Holy Spirit is not the third Person of the Trinity, as the historic Christian Church has always held, but he is an “it.” The “it” is not to be identified with the “Ultimate Divine Being” (pp. 18–19, 25), but is “an aspect or function of God Himself” (p. 116). God has many “aspects” and three of these are symbolized by the terms Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Since God is many-sided, Van Dusen feels that the doctrine of the Trinity has limited God because it expresses only three sides of God (p. 18). In any case, the term Holy Spirit does express one aspect of God. It is a symbol for his “intimacy and potency,” i.e., “God-near and God-mighty” or “God-at-hand and God-at-work” (pp. 18–19).

Having thus emptied the term Holy Spirit of all biblical and Christian content, the author is consistent in asserting that “the concept of Divine Spirit is not an exclusively or even distinctively Christian conviction” (p. 89). Just as the “belief in a triune God is not a distinctively Christian conviction” (p. 153) (the three-fold distinction within the Divine Being is to be found in the religions of Egypt, Neo-Platonism and Hinduism [pp. 151–152]), so also the concept of the Holy Spirit “appears in many religions, both of the ancient and of the modern worlds” (p. 89). On his premise that the term Spirit designates “God Present and God Active,” President Van Dusen is accurate. But it must be remembered that this has nothing to do with the biblical concept of the Holy Spirit.

Because he does not take his starting point in the Bible, he subjects the Bible to a critical process by which he accepts only those references in the Bible that conform to his concept of what the Spirit should be. Thus he considers many of the biblical characterizations of the Spirit as “sub-moral,” “sub-Christian,” and “crudely animistic” (pp. 38–39).

Whether one believes Van Dusen’s reinterpretation is right or wrong depends upon whether one has the Bible or man’s reason as his ultimate authority.

EDWIN H. PALMER

Theology For Evangelism

The Broken Wall, by Markus Barth (Judson Press, Philadelphia, 1959, 227 pp., cloth $3.50, paper $2), is reviewed by Warren C. Young, Professor of Christian Philosophy, Northern Baptist Theol. Seminary.

This volume was written at the request of the department of evangelism of the American Baptist Convention. It is recommended by this department as a basic study book in preparation for the Baptist Jubilee Advance, a united Baptist evangelistic endeavor to extend into the next five years.

Professor Barth has produced a valuable commentary on Paul’s letter to the Ephesians. Its content is fresh and stimulating. Not everyone will agree with what is said at all times. But likely there will be as much general agreement as there would be with most other commentaries.

The book is divided into four main sections. Part one is a shock treatment. Here Barth presents in condensed form some of the main points raised by critical scholarship. He by no means accepts these criticisms as is evidenced throughout the other three sections of the volume. Nevertheless, this first part is bound to leave a wrong impression in the minds of those who do not quickly grasp his purpose and style.

In the second part Barth elaborates on the central theological themes of Ephesians—the Cross, the Resurrection, and the Holy Spirit. In Paul’s presentation of the work of Christ on the cross he finds the title for his work. Christ, by his death, has broken the wall of partition and has made peace with God for us. The “Broken Wall” then becomes the symbol by which the author seeks to present our Christian obligation and activity today. This symbolism is overdone at times, yet it is often used in a highly stimulating fashion. The idea of the “Broken Wall” must be translated into action in the practical situations of our everyday experience, if Christ is really Lord of all.

Part three is devoted to a discussion of the nature of the Church. Barth rejects quite strongly both sacramentalism and sacrodotalism in his discussion of the Church and its ordinances. Such ideas, he believes, are not to be found in Ephesians, nor in other Pauline writings despite the teachings of many branches of the church today. Baptists will have little difficulty in agreeing with this presentation of the doctrine of the Church.

In the last part Barth comes to a consideration of evangelism or the work of the Church. The Church is a community of people with ethics. Our greatest evangelistic thrust will be evident when we are willing to live the Gospel we claim to believe. Be ethical, walk worthily of your calling; this is the central and basic evangelistic challenge. Christians can hardly doubt the truth emphasized here. However, the question must be raised as to what constitutes the whole function of evangelism. In the last section, “The Gospel for All,” he discusses the matter of eternal judgment versus universalism. At times he hints in the direction of universalism only to retreat from it again. He believes that Christ overcame hell by his death and resurrection, that hell is the departing empire of a lost cause, and a judgment upon Christians because of disobedience (pp. 262–263). We are sent to announce in word and deed to non-Christians their reconciliation by God and with God (p. 265). While we cannot be particularists “neither can we be universalists” (p. 265). In this paradoxical fashion Professor Barth leaves the question.

This volume does not offer a program for evangelism in the traditional sense. Barth is not interested in such a program but rather in presenting the theology and ethics which should motivate all true Christian evangelism. Will this work be a success? Probably not, but this may be in part our fault rather than Barth’s. In our modern church program we have not been strong in teaching the theology undergirding our faith. Hence, lay people studying this book may lack the perspective that is needed to appreciate the effort.

Moreover, the style of writing does not lend itself well to the purpose of the book, and the work is much too long for the study that it is intended to be. Had the author devoted himself more rigidly to his main task, leaving side excursions for another more technical study, he could have accomplished more. If pastors and other leaders are willing to study Ephesians itself and interpret to lay people the main emphases of the author, much can be gained. It will have achieved a major victory if it merely stimulates us to study Ephesians itself.

WARREN C. YOUNG

“Go Ye Therefore …”

Missionary Service in a Changing World, by A. Pulleng (Paternoster Press, 7s.6d), is reviewed by Frank Houghton, Bishop, St. Marks, Warwicks.

The first chapter of this book is entitled “The History of Missionary Work Associated with Assemblies.” And what is an assembly? It is a local ecclesia of what the world calls Plymouth Brethren (or, more specifically, Open Brethren), though its members prefer to be called simply “Christians,” and deny that they are a sect or denomination. The book is of value, however, not only to Christians of the “assemblies,” but to a wider circle. First in interest, if not in importance, is the revelation of the vast scope of the work in non-Christian lands carried on by missionaries from these “assemblies.” Their monthly magazine, Echoes of Service, published at Bath, England, has the names of no fewer than 1,155 missionaries entered in its Prayer List. They are working in 64 distinct areas, and while their emphasis is always on evangelism and the building up of believers into “assemblies” or churches, their methods include most of those used by the denominational missions, such as education, medical work, orphanages, and so forth. Nor do they neglect the more modern media of communication such as radio. Their annual missionary conference in London draws thousands of people to hear, for three nights in succession, the straightforward but thrilling stories of workers who have come direct from their fields overseas. Their organization is of the simplest. They are amongst the purest of the “faith” missions. Every missionary is sponsored as to his fitness by the “assembly” from which he comes, but there is no guarantee of financial support, though the “assembly” recognizes a responsibility to be behind him in gift as well as in prayer. “Missionary enterprise is the projection abroad of the assembly at home” (p. 13). Mr. Pulleng interprets this dictum—to which all who are concerned for world evangelization would assent—both as a challenge to the church at home to give high priority to overseas work, and a warning that the spiritual effectiveness of that work largely depends on the spiritual state of churches in the sending countries.

The second reason for recommending this book is that Mr. Pulleng lays down timeless scriptural principles for the conduct of missionary work, while giving fair recognition to the changes of the past half-century which affect their detailed application. Thus there is value for us all in “Go ye therefore …” as well as a particular interest for those who are not well-informed concerning the world-wide activities of the Brethren assemblies.

FRANK HOUGHTON

Elias Or Jeremias?

Who Do You Say That I Am, by A. J. Ebbutt (Westminster, 1959, 170 pp., $3.50), is reviewed by Frank A. Lawrence, Pastor, Graystone United Presbyterian Church, Indiana, Pensylvania.

Westminster Press advertises this book as something that will “clarify basic Christian thought.” Starting with an appeal to keep an open mind and be ready to discard traditional ideas as we approach the Bible, this churchman from the Canadian Maritimes ends up with a Jesus who, though he actually lived, is known only through a collection of error-ridden reminiscences written by nonprimary apostles, and as known, proves to be not virgin born but with moral imperfections. Though he claimed to be the Messiah, the main thrust of his public ministry was to proclaim that man was basically good and needed only to be taught to be human. The Transfiguration is said to be a vision in the mind of Peter caused by his psychological confusion about Jesus.

The author suggests we get rid of such terms as “blood,” “sacrifice,” “substitution,” “satisfaction,” and “propitiation” and bring forth a new framing addition to the Moral Influence theory which will show that “by dying on the Cross, God in Jesus dedicated Himself to the human race.” The post resurrection appearances of the Lord are explained as spiritual appearances in the form of visions objectively conditioned by the immortal spirit of Jesus who had no visible body. He terms the traditional view of hell as “a bad guess at the mystery of the future” and instructs us not to look for a literal, physical Second Coming, since the second advent has already happened many times in a spiritual sense.

The fundamental error of the Dean of the Arts Faculty at Mount Allison University in Canada is that having embraced a fallible Book he ends up with a fallible Jesus who had nothing authoritative to reveal and about whose references to eternal life we must say, “What the nature of that eternal life will be must remain a mystery. Physical research has not given any unequivocal answer to date.”

He seems unable to recognize any view of inspiration between the fundamentalist and liberal position. With the fundamentalist, he says, every word of the Bible must have been given by actual dictation of the Holy Spirit; or, in his position, the Book must be recognized as having its repetitions, inconsistencies, low ethics, and sub-Christian standards. One would expect a Canadian theologian to have passed from the old charges of bibliolatry and dictation long ago in the light of British Theologian J. I. Packer’s evidence that evangelical Protestants never held it. Carl Henry, lecturing at Union Seminary (New York), outlined the conservative position when he said, “Revelation is dynamically broader than the Bible, but epistemologically Scripture gives us more of the revelation of the Logos than we would have without the Bible. This special revelation is communicated in a restricted canon of trustworthy writings, deeding fallen man an authentic exposition of God and his purposes. Scripture itself therefore is an integral part of God’s redemptive activity … unifying the whole series of redemptive acts.”

The author has obviously read widely in the Fosdick-Anderson school, but shows a blind spot (in his material and bibliography) for conservative apologists like Berkouwer, Henry, Kenyon, and Bruce, for textual scholars like Dom B. C. Butler who turns the Markan hypothesis (which the author accepts) on its head, and for Manson of Manchester who insists there is an Aramaic document behind the Greek Q. He seems to reject what Otto has termed “mere sorry empirical knowledge” without hearkening to Craig’s observation that “such empirical facts are integral to Christianity, and if it be cut loose from them, it ceases to be Christianity and becomes a … sorry speculative gnosticism.”

The result of all this critical-historical approach is an emergency of a mild, winsome Jesus who appears out of the speculations and interpretations of buried facts and asks us, “Who do you say that I am?” To which Dr. Ebbutt would have us answer, “The philosophers, theologians, textual critics and I have given no unequivocal reply as yet.”

FRANK A. LAWRENCE