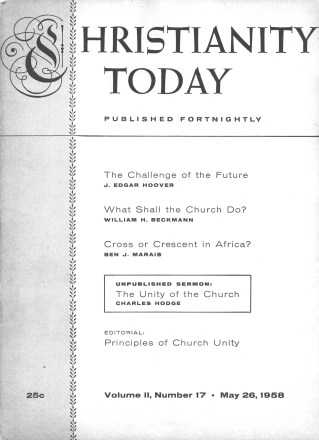

Almost a century ago—in April, 1866, to be exact—the noted Presbyterian theologian, Charles Hodge, preached a now long-forgotten sermon on “The Unity of the Church.” While voicing an impassioned plea for Protestant unity, the Princeton professor nevertheless escaped two perils that harass the contemporary ecclesiastical scene, namely, uncritical ecumenism and fragmenting independency. That this pertinent sermon remained unpublished (its outline appears in Hodge’s Conference Papers edited by his son) is one of the ironies of the times. (It should be noted, however, that the Princeton Review in 1865 carried Hodge’s article on “Principles of Church Union, and Reunion of Old and New School Presbyterians,” and that the article, incorporating much the same emphasis as the sermon, is abridged in Hodge’s book on The Church and its Polity which appeared in 1879.) The sermon manuscript was rediscovered recently in Princeton Theological Seminary library by Dr. David H. Baker, and Eternity magazine, which prints an abridgment in its June issue, has made the copy available for simultaneous use in CHRISTIANITY TODAY.

Much as Dr. Hodge’s sermon proved timely in his own day, it holds even greater relevance in ours. Its sturdy content of 6500 well-chosen words is a tribute to the congregation of William Kellogg’s church in New York City, its original place of delivery. Since Hodge gave the same message (according to his annotation) in the chapel at Princeton, on whose faculty he served for a half century, this sermon also yields an insight into the high level of seminary addresses in that day. Its primary value, however, lies in its exhibition of “the principles of Christian unity as held by the great body of evangelical Christians.”

These principles Hodge propounds with a passion both for the purity and for the unity of the Church. “Instead of conflict, we should have concord. Instead of mutual criminations, we should have mutual respect and fellowship.” If followed, the tenets he ventures to suggest would presumably transform the strained relations among churches. “Instead of rivalry and opposition, there would be harmonious cooperation … and the sacramental host, although marshaled under different banners, and organized into different corps, would still, in the sight of God and man, be one great body, glorious, and through grace, invincible.”

Professor Hodge sounds a clarion call to love; as the high and holy test of Christian discipleship, it transcends distinctions and barriers of race, color, nationality, social status and denomination. Since a vital relationship to Christ and the family of the redeemed (and not mere doctrinal conformity) is the foundation of Christian experience, Hodge emphasizes “love … founded on congeniality … not on sameness of views, feelings, affections, and objects of interest and pursuit, but founded rather on relationship.” “The want of brotherhood, the isolation of Christians, so that every one seems to be seeking his own, and not the welfare of others,” he declares, “is perhaps the most glaring defect of modern Christianity. It was not so at the beginning, and it will not be so at the end.” That this verdict was uttered not long after the Civil War permits scant comfort to our own generation to which the rebuke still applies. “One of the first evidences” that strength is returning to the Church for her conquest of the world, Hodge would still say to us, “will be the diffusion of this consciousness of brotherhood among all her members.” He even affirms that absence of brotherly love is “evidence that we are not disciples, that we have never been taught of God.”

In view of this distinct emphasis on Christian love, we are not surprised that Professor Hodge’s exposition of unity stresses the primacy of spiritual union. Those condemned for their sins and who remain in an unregenerate state are excluded from the body of Christ. Saving faith and especially the indwelling Spirit are the constituents of Christian unity. Since the indwelling Spirit is “the real bond of union between Christ and his people, and of their union one with another as members of his body,” Dr. Hodge declares it obvious “that this must determine the nature of the unity of the Church.” The Holy Spirit is “a formative, organizing principle.”

As Professor Hodge sees it, unity of the Church is not simply a matter of isolated interrelationships between redeemed individuals. “A solitary Christian is but half a Christian. There are elements of the spiritual life which can only be brought into action in organic union with his fellow Christians.” Christians must be “statedly united, not only for worship and praise, but also for prayer,” and to discriminate between those who are eligible and ineligible for admission to the fellowship of faith. Christians are to associate in visible churches. In this collective relationship the New Testament imposes upon them explicit duties including public worship, the observance of baptism and of the Lord’s Supper.

But there is more. Unity of the Church does not stop with “the inward spiritual unity of believers in faith and love,” Dr. Hodge insists, nor with “a like spiritual unity of individual, separate churches or congregations.” Specifically, “There is no reason why individual churches should remain isolated, without organic, visible union with other churches.”

It would be easy to interpret these words as a prophetic approval of twentieth century ecumenism. But close study of Dr. Hodge’s sermon yields no justification for this. Actually, what he approves and promotes is denominationalism. He maintains that “the law of the Spirit tends to the organic union of separate churches in the same way and to the same extent that it tends to the external union of believers in individual churches,” that in all ages an inward law of the Spirit motivates the Church to outward unity. “The inward unity of believers expresses itself in the outward union of church organizations” and these separate churches (Hodge calls them “organic, external societies”) thus remain one. Isolated churches that have no organic union with other churches are considered abnormal.

In keeping with Presbyterianism, Dr. Hodge affirms the obligation of individual member churches to defer to the Spirit’s rule in the larger collectivities. He notes that in apostolic times all churches were subject to the over-all authority of the specially-gifted apostles, whose power extended to church government as well as to teaching. The churches continue “one body because they are subject to one common tribunal. That common tribunal at first was the Apostles, now the Bible and the mind of the Church as a whole.…”

This combination of spiritual and external unity marked by “the subjection of each part to the whole” has never been attained, says Hodge. It nonetheless remains the Church’s proper norm. For this goal “she should strive, and … failure to attain … should be recognized as an imperfection and a sin.”

Professor Hodge’s proposals for diminishing “the evils of their external divisions” and for increasing the “spiritual fellowship” of the churches are significant for today’s ecclesiastical debate. Concerned that “the Protestant world … present an undivided front against infidelity and every anti-Christian error,” he offers five principles to advance Church unity: mutual recognition; intercommunion; recognition of the validity of sacraments and orders administered by the respective churches; non-interference; and cooperation in common causes. In view of ingenious modern solutions such as emphasis on mission more than on doctrine; on creedal broadness rather than on precision; and on mammoth superdenominational structures, what Hodge does not include in his suggested remedies is equally noteworthy.

Professor Hodge does not unqualifiedly underwrite ecumenism at any price. “We must remember … that real union is within and by the Spirit. We must begin there. And as it is there perfected it will more and more manifest itself outwardly in unity of faith, of love, of worship, and obedience.…” “External union is the product and expression of internal unity. The former cannot be safe or desirable when pressed beyond the latter.”

Moreover, Hodge particularly questions a least-common-denominator unity that blurs legitimate doctrinal considerations. Causes “legitimate and worthy of respect,” he notes, may prevent “normal unity.” Among these causes he specifically mentions “conscientious differences of opinion on questions of doctrine and order as render harmonious action in one and the same externally united body impossible.” Hodge even asserts that “as believers are imperfect in knowledge and in grace, such diversities of opinion in doctrine and order unavoidably arise which render this external union of all local churches impractical and undesirable.” Moreover, the Princeton theologian counsels: “It is better to separate than to quarrel or to oppress. Two cannot walk together unless they be agreed.” “Where two bodies of Christians differ so much either as to doctrine or order as to render their harmonious action in the same ecclesiastical body impossible, it is better that they should form distinct organizations.” Until “such unity of opinion” is attained “as to render external union practicable and desirable … all attempts at external union are premature and injurious.” Indeed, “the constantly recurring efforts to keep men united externally who were inwardly at variance” Hodge calls “one of the greatest evils in the history of the Church.” Such forced union, he declares, “leads to persecution, to hypocrisy, and to the suppression of the truth.”

It is clear that Professor Hodge supports the legitimacy of denominations over superdenominational agencies which sacrifice the lively sense of truth to the objective of unity. He specifically illustrates the divisions he has in view by reference to “Episcopalians … Presbyterians … Independents” and not alone to “Romanists and Protestants.” “The existence of denominational churches in the present state of Christendom,” he writes, “is unavoidable.”

Since believers lack omniscience, their ignorance and diversity account for doctrinal differences no less than differences in the measure of love and zeal among each other. Consequently, perfect unity continues to be a goal rather than an actuality. This lack in no way discredits Christian identification with “a common faith,” however, nor does it impugn the Church’s confidence in divinely revealed doctrines. In fact, Hodge introduces his sermon with the reminder that Church unity is among the most clearly revealed doctrines in Scripture. Similarly, his emphasis on Christian love is rooted in the authoritative biblical revelation to which he appeals again and again. Scriptural doctrines generate the first six ecumenical creeds. Through these creeds—despite denominational diversity and disagreement on nonessentials—the Church (as a regenerate body sharing the same inward religious life) retains one central creedal standard.

The scope Dr. Hodge assigns to truth as well as to love as the substance of Christian unity is therefore quite apparent. What he says to our day is worth hearing. Fragmentation is costly. So is mere external union. True unity, spiritual unity, is still a Christian imperative. It still obligates the body of Christ to fidelity both in love and in truth.

Protestantism lost a golden opportunity in Japan when she failed to take advantage of the unprecedented opening for Christian missions following World War II. The chance for wholesale impact has now been lost but that nation is still wide open as a field for evangelistic endeavor, and while the missionary (fortunately) is no longer on a pedestal he is needed and he is welcome.

Technical aid and educational experts in missions are indeed necessary, but the great need is still for men and women to preach and live the Gospel in the midst of a people who have a great culture and the highest literacy rate in the world, so few of whom know Christ.

The Synod of Kyushu, which measures in number of churches and believers about one-tenth of the United Church in Japan (Kyodan), has made a careful evaluation of the work of that area, the unreached cities and villages and the need for additional evangelistic missionaries to aid in reaching the people of Japan with the Gospel.

A copy of this significant report has been forwarded to this paper by the Rev. Osamu Murakami, pastor of the Yahata Kyodan Church and a member of the standing committee which prepared the report.

Mr. Murakami solicits the prayers and help of those interested and writes: “We welcome missionaries.”

This report is of more than passing significance because it points up the present trend of the eight cooperating boards operating as the Inter-Board Committee to send missionaries into institutional rather than evangelistic and pastoral work.

The fact that the Japanese church is asking for more ordained missionaries to come to share in pastoral and evangelistic work is also significant. This report states that less than half as many ordained evangelistic missionaries have been sent to Kyushu as before the war and that now the number of missionaries engaged in church extension is extremely small, while eighteen cities are mentioned in which there are no churches of any denomination.

One solution suggested is the waiving of retirement age for elderly missionaries in that area.

Japan desperately needs the Gospel and the Japanese Christians and the Japanese church continue to welcome missionaries. That they are pleading for pastors and evangelists should be a source of thankfulness and a challenge to those who are willing to heed the Great Commission.

Here is a challenge to men and women who have dedicated their lives to our Lord. It is a challenge because of the need and also because of the difficulties. An old and proud culture, a complicated language and many difficult adjustments are some of the obstacles in the way of an effective witness. But the rewards will be both immediate and eternal.