The church is often numbered, with the capitalists and the social system, among the culprits of the last century. It is accused of being blind to social needs and conservatively in partnership with the ruling and property class. The church is, therefore, deemed responsible for her own apostasy and accused by some for the rise of communism. Even churchmen have made such a charge. The accusation that the church has failed is voiced so systematically, with such generality and onesidedness, that one cannot help asking whether there is something ulterior behind the charge.

Much indeed may be blamed on the church and on its membership, too, for that matter. It is not my intention to create the impression that the church did all that she could. Far from it. Sometimes she was helpless because of her subordinate position to the state, as in Russia and Scandinavia. In England this was true of the established (Anglican) Church and in the Netherlands of the Dutch Reformed Church. An independent formulation and critique of the social situation, which in such a case had to be directed against the state as well, was practically impossible. In addition it must not be forgotten that some churches were preoccupied with internal troubles and schisms. Wanting in its protest and falling short in love, the church was saved from going down ingloriously only through the protecting care of her Lord and Saviour.

Has the church failed to make a true effort to solve the social problems brought about by the industrial revolution of the past century?

It is well to take cognizance of several factors that have been given little consideration. First of all, such one-sided criticism loses sight of the fact that the church was also caught by surprise by the tempo and the radical character of the industrial development. Within the church people were disposed to think that no solution of the problems was possible. Moreover, the prevailing distress must be estimated by a comparison with most unfavorable social conditions of former times. One should put himself in the time in question since hindsight is always easy.

Not Without Protest

Before general charges are made that the church was indifferent to her obligations, evidence should be brought forth that the pulpits of the day were completely without protest. Many nineteenth-century Christians did indeed voice their alarm, and the pulpit was not so silent as some critics contend.

Task Of The Church

When the church is reproached in this connection, it must be borne in mind that many assign her a much broader task than that to which she has been divinely called. Critics frequently ignore the fact that the enlarging denial of the Christ of the Scriptures had produced decay and impotence in the church of the nineteenth century. It is a striking feature of pagan criticism that the secular world is always excused. Humanism, socialism and even communism are held up to the church that she may learn how social problems should be handled. The message of Christ is reduced to just a gospel of social justice. To ease the pain of such criticism the observation is offered that if the church would really tackle the question, she would do it “much better.”

The delimitation of the message of Christ to social justice is related to the breakthrough propaganda (the de-Christianization of hitherto Christian organizations) and the high-church movement, which looks upon the church as a national, all-embracing institution.

When irrationalism and dialectical theology obscure the clarity of the Bible concerning believers, and when the radical character of the biblical message against apostasy is forgotten, it is not difficult to cling to the idea of a church for everyone and to eradicate the boundaries between the church and the world, between Christian and so-called neutral activities. Then the sympathetic concern for social problems and the anxiety about the cultural decline, point the way. The church becomes the fulcrum, social justice becomes the goal, and socialism carries the standard of honor. Some would add characteristically dialectical statements in which the exception becomes the rule, e.g., “A man who turns his back upon the church, may by that very attitude be saved religiously”; “The church must learn from socialism”; and “A humanist may very well be a better Christian than the man who goes to church twice every Sunday.”

Of course not every follower of Barth nor every adherent of neutralization and secularization of organized life subscribes to such reasoning. The taste for paradoxes is specially reserved for extremists. Nevertheless such views do prevail, and their adherents believe that the church of the previous century was the chief culprit in the prevailing social misery.

Christian Community

Much of what we have said here applies to the Netherlands. In the United States the idea of a Christian organization (or, more generally, an organization based upon a particular view of life and the world) is unknown. An important reason for this lack of explicitly Christian organizations is the strong sense of solidarity prevailing among the Americans, due to necessity as much as to the desire of the people to be a nation in the face of the diversity of origin among Americans. This sense of solidarity is intensified by the fact that they are a young nation and an enthusiastic and dynamic people.

Social Justice Derivative

Many Christians who turn to socialism seem to discover in the Bible only one subject: the social problem and the demand for social justice. This theme does indeed play a great role in the Old and New Testament; and yet it is but one of many (Exod. 21; Gal. 5; Col. 3). Besides, it is a derivative motif. The Bible does not view social injustice by itself but as the consequence of a greater evil, the source of all evil, namely, that men do not fear God and do not keep His commandments but bow down to idols (2 Kings 17). (The present idols seem to be man and society.) Such is the fountainhead of life’s errors, the source of humanism, irresponsible capitalism, social distress and the impotence of socialism.

Some may argue that the root cause of our difficulty is not forgotten. But the fervor of their argument and their systematic neglect of certain aspects of the problem makes me fear that this knowledge is cerebral and that their heart lives in the social issue only. Such are aroused when trangressions of the eighth commandment, “Thou shalt not steal,” and the tenth, “Thou shalt not covet,” are viewed as a commandment meant for others. The level of the socialists is thus indeed reached, but the Gospel is forgotten as something inseparable from the exordium: “I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee up out of the house of bondage.”

Allow me to put it most boldly. The whole social problem is absolutely of no importance when compared to the command to fear the Lord. Any Christian that places human relationships on a par with the relation between man and God, or regards the human sphere as separate and independent of the latter relation, thereby discloses that his Christianity has been infected by humanism.

The Chief Commandment

The command, “Love thy neighbor,” is a Christian precept, but when detached and removed from the framework of the great commandment, “Love the Lord thy God with all thy heart …,” it ceases to be such, in a very real sense. It is likewise erroneous to think that compliance with the command to love one’s neighbor is at the same time a fulfillment of the chief commandment to love God.

The humanizing phenomenon is so frequently encountered. In it the call of God and the obligation to serve him as an individual and in a group is replaced by the call of the other man and finally by the call of man himself, of his needs, the only source of his motivation. The process of humanizing reality has also influenced Christian circles. When Sargent, considering the challenge to the church, looks for basic concepts of the Christian action, he states: “The first of these basic concepts is the biblical idea of human dignity and individual personality.” This is, however, an unbiblical statement of man and a mere profane view of life.

Consider also a few quotations from Kuylaars (Werk en Leven), 1951, pp. 20, 36): “Labor is a realization of self.” “In industrial enterprise the laborer is central and primary. Capital is simply an aid; it occupies a secondary position, together with those who supply it.” This statement is intended as a reply to liberalism but this answer is wrong; the laboring man is not central. In this case the fruits of labor as the fulfillment of the cultural task are central.

It has been maintained that the aims and purposes of the communal life must be directed toward man. Aberrations of this kind are surely not innocent. They put Christians on the wrong track in their planning and their deeds. For example, Pedersen writes: “If ever peace and righteousness are to exist among men, then their material necessities must be satisfied, so that distress and want shall disappear. But this can be done only with the help of technique” (God en de Technick, p. 153). Peace and righteousness, however, come when man is reconciled to God. Both may be present even when distress and want exist. Both may be lacking, as in today’s secularized world, when distress and want are in fact relieved. Such is the Christian outlook on life an outlook which is the direct opposite of socialism.

END

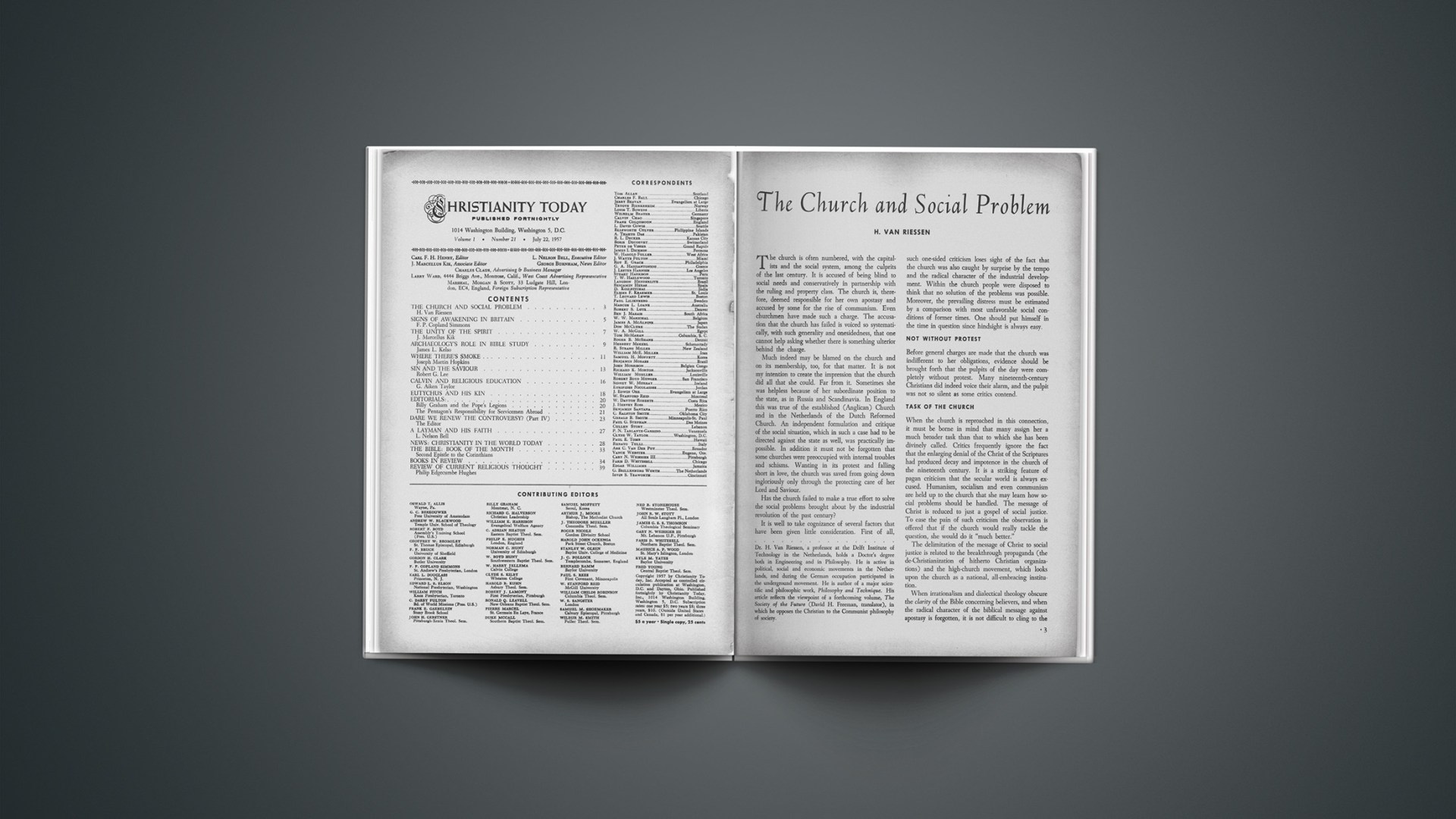

Dr. H. Van Riessen, a professor at the Delft Institute of Technology in the Netherlands, holds a Doctor’s degree both in Engineering and in Philosophy. He is active in political, social and economic movements in the Netherlands, and during the German occupation participated in the underground movement. He is author of a major scientific and philosophic work, Philosophy and Technique. His article reflects the viewpoint of a forthcoming volume, The Society of the Future (David H. Freeman, translator), in which he opposes the Christian to the Communist philosophy of society.