In this series

Sometime in the early 1490s, probably between 1493 and 1495, a son to be named William was born to a Tyndale family that lived near the Welsh border. The Tyndales (who also called themselves Hutchins) were an important family in the west of Gloucestershire, but William, together with at least two brothers, apparently came from a lesser branch of the family.

Around 1512, Tyndale went as a student to Magdalen College at Oxford, which at that time was a sort of prep school attached to the university. At some point after gaining his M.A. in 1515, he moved to Cambridge University for a time. Cambridge was rife with Lutheran ideas around the early 1520s, and it’s likely he acquired his Protestant convictions while studying there, if not before.

At a later date he expressed his dissatisfaction with the teaching of theology at the universities: “In the universities they have ordained that no man shall look on the Scripture until he be nozzled in heathen learning eight or nine years, and armed with false principles with which he is clean shut out of the understanding of the Scripture.”

In 1521 he left the university world to join the household of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury Manor, north of Bath. It’s unclear exactly what role he played in the household—he may have been the chaplain or a secretary to Sir John—but most probably he was a tutor to the children.

Many of the local clergy came to dine at the Walshes’ manor, which gave Tyndale ample opportunity both to be shocked by their ignorance of the Bible and to become embroiled in controversy with them. To one such cleric he declared: “If God spare my life, ere many years pass, I will cause a boy that driveth the plow shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost.”

Here Tyndale was echoing Erasmus’ famous inscription in the preface to his Greek New Testament: “I would to God that the plowman would sing a text of the Scripture at his plow and that the weaver would hum them to the tune of his shuttle.”

Tyndale began to clearly feel the call to translate the Bible into English and distribute it. At this time the only English translation available was the hand-copied Wycliffe Bible, which was distributed clandestinely by the Lollards, the followers of the 14th century’s John Wycliffe (see Christian History Issue 3). But this had never been printed. Furthermore, it was inaccurate in many ways, having been translated only from the Latin Vulgate, rather than from the original Greek and Hebrew.

Ban the Bible!

Because of the perceived threat of the Lollards, the Church had in 1408 banned translation of the Bible into English. So Tyndale left Little Sodbury in search of ecclesiastical approval for his projected translation. He went to London and obtained an interview with the bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall.

This was a shrewd choice, as Tunstall was a scholarly man and a friend of Erasmus. But at that time, Tunstall was more concerned to prevent the growth of Lutheranism than to promote the English Bible, so Tyndale received no encouragement from him. Tyndale soon perceived that “not only was there no room in my lord of London’s palace to translate the New Testament, but that there was no place to do it in all England.”

The frustrated translator briefly lived in London, where he received financial support from a wealthy cloth merchant named Humphrey Monmouth. With the backing of Monmouth and other merchants, Tyndale resolved to leave the country in order to engage in the work of translation on the Continent.

So in 1524 he sailed for Germany, never to see England again. In Hamburg he worked on the New Testament, which was ready for the press by the following year. A suitable printer was found in Cologne, and the pages began to roll off the press. But one of Tyndale’s assistants spoke too freely over his wine, and news of the project came to the ears of Johann Dobneck, alias Cochlaeus, a leading opponent of the Reformation. He arranged for a raid on the press, but Tyndale had been warned—just in time, he fled with the pages thus far printed. Only one copy of this incomplete edition survives.

Tyndale moved to Worms, a more reform-minded city, where the first complete New Testament printed in English was published the following year. Of the 6,000 copies printed, only two have survived. Yet this scarcity is easily explained. As more and more of the small testaments trickled into England, the bishops there did all they could to eradicate them. In 1526 none other than Bishop Tunstall preached against the translation and had copies ceremoniously burnt at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Buy the Bible?

The following year William Warham, the archbishop of Canterbury, had the ingenious idea of himself buying up copies of the New Testament in order to get them off the market and then destroy them. Unbeknownst to him, the substantial monies he paid simply provided Tyndale with funding to produce a better, more-numerous second edition!

In 1530 Tyndale’s translation of the Pentateuch was printed at Antwerp, where he had now settled. There were also several further editions of the New Testament. Tyndale continually revised the translation in the light of suggestions received and of his own further thinking. Some, but not all, of the editions contained marginal notes. The purpose of these was mainly to explain the meaning of the text, though at times Tyndale could not resist the temptation to apply the text against the papacy.

Tyndale translated directly from the Greek and Hebrew, with occasional reference to the Latin Vulgate and Luther’s German translation. His style is homely and intended for the ordinary man, in keeping with his original aim to make the Bible widely accessible. In this extract from the 1526 edition (Romans 12:1–2), the original spelling has been retained. But the foretaste of English translations for centuries to come is obvious:

“I beseeche you therefore brethren by the mercifulness of God, that ye make youre bodyes a quicke sacrifise, holy and acceptable unto God which is youre resonable servynge off God. And fassion note youre selves lyke unto this worlde. But be ye chaunged [in youre shape] by the renuynge of youre wittes that ye may fele what thynge that good, that aceptable and perfaicte will of God is.”

Tyndale planned to complete the translation of the Old Testament. In 1534 he attained a position of greater apparent security. He took up residence with the English merchants of Antwerp, as the guest of Thomas Poyntz, a relative of the Lady Walsh of Little Sodbury. The merchants paid him a regular stipend, and his influential hosts would have afforded him a certain measure of protection. But his newfound security proved to be illusory. In May of 1535 he was betrayed by a fellow Englishman named Henry Phillips.

Trap the Translator!

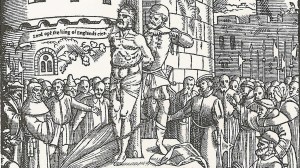

This villain gradually befriended Tyndale, then induced Tyndale to venture onto the streets of Antwerp with him. There, Phillips signaled soldiers who ambushed Tyndale and seized him while he was walking down a narrow passage. He was taken to the state prison in the castle of Vilvoorde, near Brussels. After a year-and-a-half of confinement, Tyndale was strangled, then burnt at the stake in Brussels on October 6, 1536. His last words, reportedly, were “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes!”

The authorities in England banned Tyndale’s translation, and destroyed every copy that they found. But they did not find them all, and the influence of those that survived, as well as of his other writings, was considerable. And this even during the reign of Henry VIII who, despite Tyndale’s prayer, continued to adamantly oppose Protestantism.

In 1535, while Tyndale was ebbing in prison, Miles Coverdale published the first-ever complete printed edition of the Bible in English, and received royal approval to distribute it. For diplomatic reasons Tyndale’s name did not appear in it, though the translation was hugely dependent upon his work.

To its advantage was the fact that by this time England had an archbishop of Canterbury (Thomas Cranmer) and a vicar-general (Thomas Cromwell), both of whom were committed to the Protestant cause. They persuaded Henry to approve publication of the Coverdale translation, and by 1539 every parish church in England was required to make a copy of the English Bible available to all its parishioners. All the available translations were substantially based upon Tyndale’s. Thus while Tyndale had not been personally vindicated, his cause had triumphed, as had his translation.

Tyndale can justly be called “the father of the English Bible.” It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that almost every English New Testament until recently was merely a revision of Tyndale’s. Some 90 percent of his words passed into the King James Version, and about 75 percent of them into the Revised Standard Version.

Certainly he was famous as a Bible translator, but this was by no means his only work. He wrote a number of books, of which the most-famous are his The Parable of the Wicked Mammon and The Obedience of a Christian Man. The theme of the first book is justification by faith alone. It was heavily dependent upon Luther, in fact in some places it was merely a translation of Luther.

But it was original enough to show that Tyndale was not just parroting Luther, though he was more “Lutheran” than most of the succeeding reformers. The second book argues that Christians always have the duty of obedience to civil authority, except where loyalty to God is concerned.

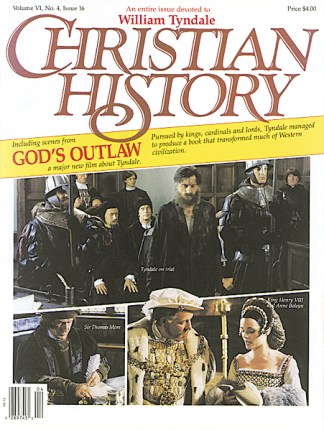

Tyndale is also famous for his literary battles with Sir Thomas More. In 1529 More attacked this “captain of the English heretics” in his Dialogue Concerning Heresies. Two years later Tyndale replied with an Answer to More. More responded with a tedious Confutation, two weighty volumes published in 1532 and ’33.

The two men were unable to agree because of their different starting points. For More the true church was the historic Roman Catholic Church, which he deemed as infallible. Anyone who opposed the pope, any of his representatives, or the official church doctrine, was in More’s eyes a heretic. It was because of this belief that More had many “heretics” burned at the stake, and it was because of this belief that he himself was prepared to go to the scaffold.

For Tyndale, on the other hand, the true authority for faith was to be found in Scripture, and any person or group who denied the authority of Scripture was in his perception under the control of Antichrist. This belief carried him to the scaffold, but it also lifted up and carried the movement that came to be called “the Great English Reformation.”

Dr. Tony Lane is a professor of Bible at London Bible College. This article is expanded from a chapter he wrote for the forthcoming book, Great Leaders of the Christian Church (Moody Press, 1988, edited by John Woodbridge)

Copyright © 1987 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.Click here for reprint information on Christian History.