In 1926, an African American newspaper editor in Topeka, Kansas, announced his candidacy for the United States Senate. His name was Nick Chiles. Although a black person had not occupied a Senate seat since 1881—and would not do so again until 1967— Chiles had grown disgusted with Kansas Senator Charles Curtis’s unwillingness to fight for the voting rights of black Southerners.

So, Chiles decided to take matters into his own hands. His campaign platform included eight planks, most of them focused on ending Southern segregationist control of the Senate, re-enfranchising African Americans, and guaranteeing workers a living wage. It also included a plank that made Chiles’s righteous indignation clear: “The Holy Bible for my Guide.”

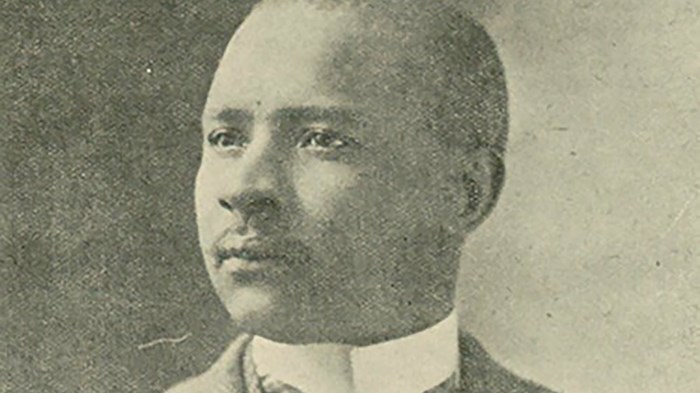

Despite his reliance on the Bible, Chiles is not the most obvious candidate to receive a biographical feature in Christian History. Mostly forgotten today, the South Carolina–born entrepreneur, activist, politician, and journalist set up shop in Topeka, Kansas, sometime in the 1880s, living there until his death in 1929.

He was best known in his early years for engaging in perhaps the greatest evil a late 19th-century evangelical Protestant could envision: the liquor trade. By the 1890s, white newspapers in Topeka were complaining about the “notorious negro jointist” who was "never punished for crime" and "perpetually petted and cuddled" by white Republican leaders in the city.

Yet Chiles evolved. He used his saloon business to launch more respectable enterprises. A 1922 profile of Chiles glowed: “He came to Topeka with only fifteen dollars in his pocket, but he now owns a $7,000 plant, his own building, a fine residence, and a large amount of other property." Most important to Chiles’s mini-empire was his newspaper, the Topeka Plaindealer,arguably the most prominent Western black newspaper in the early 20th century.

Chiles also added to his respectability by getting religious. He joined Topeka’s St. John AME congregation in 1910 (he would remain a member there for the rest of his life). Upon hearing of Chiles’s decision to join a church, one friend declared that the millennium must be at hand. Yet if Chiles-the-churchman was a new development, his interest in religion was not. While Chiles was a complex figure who, as one observer marveled, “could pose on four sides of every one question, and come out unscathed,” there was at least one consistent theme in Chiles’s lifelong anti-racism activism: appeals to the Christian principles of white Americans.

What Would Jesus Do?

In Chiles’s lifetime, the most famous Topekan was Congregationalist minister Charles Sheldon, author of best-selling social gospel novel In His Steps (1896). Sheldon’s book urged Christians to ask “What would Jesus do?” in their daily lives, a question that would resonate in American Christian circles long after Sheldon passed away (if you or someone you know has worn a “WWJD” bracelet, you know what I mean).

In early 1900, a few years after publishing In His Steps, Sheldon announced that he would be taking over the operations of Topeka’s most prominent newspaper, the Topeka Capital, for one week. Sheldon planned to run the paper “as Jesus would” in hopes of providing a model for other newspapers to follow.

Sheldon had a good reputation among Topeka’s black residents, his church often providing resources for impoverished black residents in the city. Thus, Chiles’s Topeka Plaindealer responded enthusiastically to Sheldon’s idea, believing that, for one week at least, a white newspaper would take a serious interest in the problem of racism in American society. "There is no doubt in our mind if it were possible to conscientiously answer the question ‘What Would Jesus Do’ that the Jim Crow car, lynchings...and burning of poor defenseless Negroes would pass away,” a Topeka Plaindealer editorial declared.

But Sheldon’s stunt was a letdown. “Rev. Sheldon has accomplished one thing … if all else was disappointing,” the Topeka Plaindealerlamented at the end of the week. “He used the upper-case ‘N’ in Negro. We know that’s what Jesus would do?”

It was perhaps because of this experience that Chiles decided he could not rely on sympathetic white Christians to make anti-racism a priority; he would need to confront white Christians himself. Chiles came to believe, as he explained in 1905, that his newspaper was not directed solely at the black community but was also a means of “educating the white man in the moral duty that he owes the colored man as a citizen of the United States of America."

Corresponding with the Curia

The most dramatic way in which Chiles sought to prick the consciences of white Christians came in 1903–04. Following the death of Pope Leo XIII and the appointment of his successor, Pope Pius X, the Western Negro Press Association—an organization led by Chiles—decided to send a message of congratulations to Pius X, combined with a request.

The WNPA’s message asked the Pope to speak out against racial discrimination in Catholic-dominated labor unions and in American society more broadly, since “the Protestant church in America, except in a few rare individual instances, seems to be deaf to our appeals and seems inclined to remain silent if not actually acquiescent in the terrible outrages upon us.” Because American Protestants combined cultural dominance with a strong suspicion of Catholicism in the early 20th century, asking the Pope to speak out against racial oppression carried an especially sharp edge.

Eight months after sending its message to the Vatican via a Kansas senator, the WNPA received a reply, written by Pope Pius X’s secretary:

His Holiness, as the Vicar of Christ, extends his loving care to every race without exception and he must necessarily use his good offices to urge all Catholics to befriend the Negroes who are called, no less than other men, to share in all the great benefits of the Redemption. … While frankly admitting that crimes may often be committed by members of the Negro Race, His Holiness advocates for them the justice granted to other men by the laws of the land and treatment in keeping with the tenets of Christianity.

Read today, the Pope’s letter seems unremarkable, perhaps even harmful with its “crimes may often be committed” language. Yet, for Chiles and the WNPA, it was a triumph: Finally, a white Christian leader seemed to be listening and responding to their concerns. The headline in Chiles’s Topeka Plaindealer reprinted the Pope’s reply under this headline: “With Several Million Christians in This Country Like His Holiness Pope Pius X, the 'Land of the Free' Would Be a Reality!"

The Pope’s letter received widespread attention from white newspapers when the Associated Press reprinted excerpts and a brief summary. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, we know that it did not bring widespread changes to the behaviors and practices of white Americans. But that did not stop Chiles from continuing to confront white Christians with the contrast between the ideals they claimed to profess and the reality of racism in American society.

Interview with a White Supremacist

In 1913 Chiles took his crusade to the office of South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman, a virulent racist. In a series of four letters, two written by each man, Chiles urged Tillman to repent of his racism and accept black people as equals, while Tillman defended his belief in white supremacy.

In his initial letter, Chiles remarked that he had not "heard of anything uttered by you for the last few months that would indicate that you were still opposed to the progress of the colored people” and asked Tillman if this was a sign that the senator’s views on black people had changed. Chiles urged Tillman to use his political power to encourage the uplift of black people. “It is your Christian duty to help undo the great injustice that has been perpetrated upon them," Chiles wrote, adding that “if this is accomplished you will merit the prayers of thousands, for there are many praying Christians of both races who are striving to bring about this change."

Tillman responded by informing Chiles that he still believed strongly in white supremacy. He even forwarded some of his speeches on that theme for Chiles to read. "I like them [black people] much better in their places than I do dagoes; but out of their places, I have no use for them whatever,” Tillman told Chiles. “There is only one attitude they can assume with safety to themselves. That is acknowledgement of white supremacy. Anything else will doom them to extermination."

Chiles sent a lengthy reply that asked Tillman to explain how he, as a Christian, could oppose equality for black Americans. "Now, I would like to know if you are a Christian and believe in the Holy Bible, the Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ and if you acknowledge the colored man as an American citizen and subject to the rights of the constitution that you enjoy," Chiles demanded. Chiles concluded by expressing his desire that “you will play the part of Paul of Tarsus ... and will see the errors of your way and will call a halt on your white brethren who believe as you do on the race question, and thereby cause a complete revolution in this country on this question."

In his reply, Tillman merely asserted his continued belief that “the white man” was “the superior race of the world” and told Chiles to stop writing him. Chiles, meanwhile, took the four letters and reprinted them in his Topeka Plaindealer. He included a preface that showed empathy for Tillman, noting that the senator’s racism could be partly excused because it was “bred and born in him.” Even so, Chiles wrote, “we pray that the Lord will spare him long enough to see the error of his way before the final day.”

Chiles’s correspondence with Tillman is indicative of his anti-racism approach. For Chiles, white supremacy was a sin that needed to be confronted and exposed in a direct way. By corresponding with Tillman and publishing the letters in his newspaper, Chiles hoped to bring attention to the beliefs of white supremacists and provide white Christian readers with an opportunity for moral and ethical reflection on their possible complicity in racism.

A Persistent Provocateur

Other examples abound of Chiles’s penchant for invoking Christianity when denouncing racism. At the opening ceremony of a meeting of AME leaders in Topeka, Chiles urged black churches “to pray for the white race to help them in their morals.”

In 1914, one week after President Woodrow Wilson declared a national day of prayer, Chiles sent a telegram asking the president to “name a day of prayer to stop the lynchings and other outrages that are heaped upon the colored Americans of these United States. They are the only ones who suffer abuses inflicted upon them by the so-called Christians. Believing you a Christian gentleman, you could not do less than to obey such a request."

After the 1921 riots in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in which a white mob decimated the city’s thriving black community, Chiles sent a telegram to the Oklahoma governor expressing outrage and regret at the way such actions “reflect on Christianity.”

In 1925, Chiles wrote to the Georgia governor, informing him that white citizens in Georgia needed to undergo a Christian education program until they were willing to “stand up for decency, Christianity, and brotherly love” and ensure “that no citizen in the confines of [Georgia] will be wrongfully elevated over another."

Of course, the extent to which Chiles’s words and actions resonated with white Christians is difficult to determine. But the key point is that he tried, constantly confronting white Christians with his belief that racism was a sin and that it was widespread in a society that was supposedly filled with Christians. Indeed, while Chiles fought for specific laws that would protect the rights of black Americans, he firmly believed that the problem of racism in the United States was a spiritual problem that would not be solved until the consciences of white Christians could be awakened.

It is precisely because of those efforts that Chiles’s inclusion in Christian History—a magazine historically embedded within the institutional structure of white evangelicalism—makes sense. Or at least, it would make sense for Chiles. Were he alive today, it is not difficult to imagine Chiles observing the continued presence of racism in American society and taking any opportunity he could to confront white Christians with some questions: Is this consistent with Christianity? And if not, what are you going to do about it?

Paul Putz recently completed a dissertation at Baylor University on the history of Christianity and sports in the United States. Beginning in August 2018, he will be a lecturer in American history at Messiah College. You can read more about his work here.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month