The sounds of engines revving fill the opening seconds of Mad Max: Fury Road, and they continue pretty near constantly for the duration of the film, a dystopian road movie that is essentially one gigantic, heart-pumping, gritty-yet-artisanal chase sequence.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.Who is chasing whom, and why, is less important than the outrageous cinematic fodder it serves up: a baroque-meets-heavy metal visual and aural feast, encapsulated in one of the film’s many over-the-top showpieces: an electric guitar that doubles as a flamethrower.

Pure cinema.

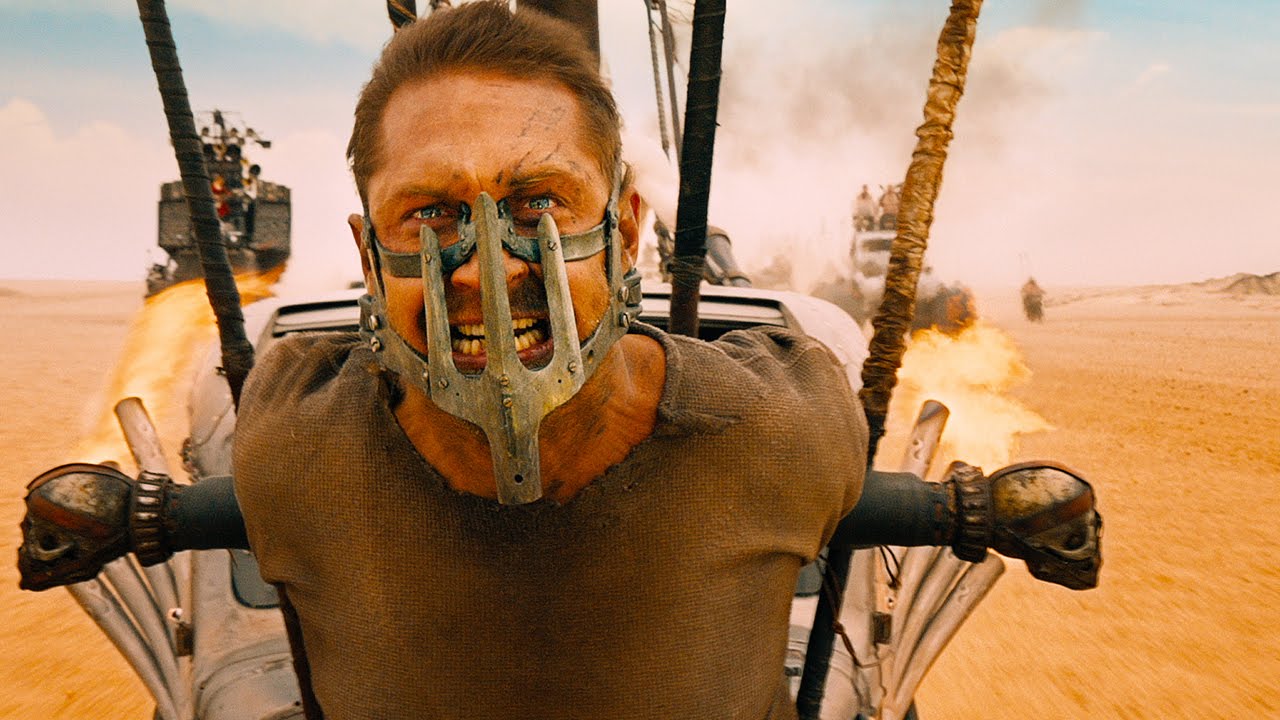

The fourth installment in George Miller’s Mad Max franchise (and the first in 30 years), Fury Road opens with Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy taking over the iconic Mel Gibson role) situating us in the film’s scorched earth, post-apocalyptic setting. He sums it up when he says, “My world is fire and blood,” where everything “is reduced to a single instinct: survive.”

“As the world fell, each of us in our own way were broken,” notes Max, who takes a bite out of a double-headed lizard in the fist few minutes of the film. This is indeed a fallen, hellish world: physical and spiritual deformity abound, mutations of a once-ordered world that is now all chaos, crows, twisted metal and gasoline.

In the midst of this land, aptly called Wasteland, there exists a sort of anti-Eden metropolis called the Citadel, ruled by a tyrannical overlord named Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne). With its skull-heavy aesthetic, preponderance of child slaves, pagan worship rites and zombie-like bald henchmen with heavy eye makeup, the Citadel bears a striking resemblance to the Temple of Doom from Indiana Jones.

Unlike the Eden of Genesis, a temple-like oasis ultimately meant to bring order, flourishing, and blessing beyond its borders through the stewardship of Adam, the Citadel is a closed imperial fortress where water and greenery are kept out of reach (literally high on cliffs) from the starving, parched masses. “I am your redeemer,” says Joe from his perch on high, perpetuating a cult religion that depends on keeping the throngs just happy enough. Water is ceremoniously released to them in small batches, with Joe saying things like, “Do not become addicted to water . . . you will resent its absence.”

This logic, of ensuring submission by promising some level of security and comfort, manifests itself in the various forms of slaves (child slaves, blood donor slaves, breast-milk producing slaves, etc.) kept in Joe’s palace. His “five wives” are sex slaves, “prized breeders” who perpetuate his kingly line.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The plot of Fury Road kicks off when a woman named Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) smuggles the five wives out of captivity in an oilrig, with hopes of taking them to destination of freedom called “the green place.” A massive chase ensues, featuring all manner of vehicles (think military-meets-muscle cars) and weaponry (guns, knives, bombs, chainsaws, I think I even saw a scythe) as Joe and his “war boys” (essentially kamikaze albino jihadists) pursue Furiosa and the five wives.

After spending much of the first half of the film as a human hood ornament, donating blood to the driver of a car as it careens through the desert at high speeds, Max eventually joins up with Furiosa, though more as a sidekick than a hero. Max has his moments, to be sure, but this is Furiosa’s film. By the time the protagonists join forces with a motorcycle gang of guerilla grandmas called “the many mothers,” it’s clear that a key theme of Fury Road is feminine power and redemption. Like Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof, Fury brings a bit of a feminist critique to a traditionally masculine, exploitative genre.

Somewhat related to the film’s gender politics, one might also pick up a subtle critique of radical Islam. In their world of oil and deserts, the “war boys” bear resemblance to ISIS fighters and jihadi militants, not only in their view of women as prizes and property but in the way they thrill in violence, shock, terror and glory.

“If I’m going to die I will die a historic death on Fury Road,” says one war boy (Nicholas Hoult), who along with his cohorts manifests an almost nihilistic embrace of mayhem, destruction and death for the sake of achieving a place in “Valhalla” (in Norse mythology, the afterlife home for warriors who die in combat).

“I live, I die, I live again!” he shouts on more than one occasion.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The pseudo-religious language of death and subsequent glory in the afterlife is one of the rare touches of transcendence in the film. On another occasion a character is seen fumbling with her hands in a prayer posture, trying to petition “anyone who’s listening.” This is a post-God world, bereft not only of most forms of life but, naturally, most belief in a God who might care.

And yet the film hints at an Edenic renewal and redemption from the ashes. If Joe (an antichrist type) can be overthrown and his reign of terror ended, perhaps the seeds of the fabled “green place” could be replanted? Instead of the “anti-seeds” of guns (“plant one and watch something die”) and the ever-present machinery of death, life might once again thrive.

Fury Road is a furiously visceral, non-CGI experience, throbbing with pounding music (composed by Dutch producer Junkie XL) that accentuates the film’s bloodletting and bone-crushing highway to hell. It’s a road that goes nowhere but exists only for itself, meaningless mayhem in a world where any connection between signifier and semiotic object seems quaint. A tree is referred to as “that thing.” Language has morphed into indecipherable grunts, chants and war cries. Viewers see all sorts of nonsensical things on screen that defy meaning or explanation. It’s anarchy, but that is the point.

Death is the only logic of this barren landscape, where people eat spiders as snacks and babies are cut out the wombs of dying women. And yet where there is disorder and death, there is hope for order and life. The apocalyptic energy of the film seethes with an eschatological longing for renewal and restoration. The way cinematographer John Seale focuses on color (vibrant primary hues of yellow, red and blue), the way the operatic music and sense of ceremony accompanies the chaos, are but some of the hints that a deeper magic and meaning exists in the universe.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The world of Fury may be desolate and war-torn, languishing under the failed stewardship of man. But as another recent film, Wim Wenders’ Salt of the Earth, shows us, nothing that can die is beyond the hope of resurrection. The “things fall apart” inertia of this sin-stricken world is not irreversible. Order wins in the end; goodness will triumph over madness.

Caveat Spectator

Mad Max: Fury Road is one of those films that foregrounds and aestheticizes violence, similar to the films of Quentin Tarantino or Robert Rodriguez. As such, violence of all sorts abounds: gunfights, knife fights, spear fights, crashing vehicles, explosions, impalings, people getting run over, pregnant women falling off of moving cars, dead babies being cut out of wombs, a man’s jaw being ripped off, etc. The film is rife with brutality, though many of the most violent moments are not shown explicitly as much as they are implied and cut away from at opportune moments. For as constant as the violence is in the film, it is not as explicit as it could be. In addition to the violence, there is some profane language, a few quick (non explicit) shots of female nudity, and a lot of so-called “disturbing images” of deformed people and scary looking villains. In general, though it is certainly deserving of its R-rating, Fury Road is not as explicit as it could be, given its aim to show a world of depravity and chaos.

Brett McCracken is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist, and author of the books Hipster Christianity: When Church and Cool Collide (Baker, 2010) and Gray Matters: Navigating the Space Between Legalism and Liberty (Baker, 2013). You can follow him @brettmccracken.