A movie poster proclaims “Not Suitable for Children” and “Twin Cities of Sin”; lurid couples adorn the background, caught in compromising positions, and the lower half of the poster boasts two beautiful people caught in passionate lip-lock.

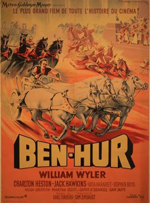

A sleazy summer blockbuster? The latest “edgy” art house fare? No: it’s from a 1963 movie, one of the later members of the “sword and sandal” genre of films based on the Bible, which also includes Ben-Hur, King of Kings, and The Robe.

Granted, this film is called Sodom and Gomorrah

The poster, and other surprises, is currently at the Museum of Biblical Art (MOBIA) in New York City. The museum’s “Reel Religion” exhibit, on view until May 17, is a survey of Hollywood films based on the Bible.

Not only does the exhibit show what a rich source of material the Bible has been to filmmakers, but it’s is also a revealing look into the tactics that studios have used in the past hundred years to market films, and the ways that stories drawn from biblical narratives have fit into Hollywood.

“Reel Religion” is mostly made up of movie posters, drawn heavily from the collection of Father Michael Morris, a Dominican priest, prolific author, and professor at Berkeley. When he began collecting the posters to display, members of his department were initially delighted.

“‘Finally, something uplifting on the walls!’ they said. Little did they know!” recounts Morris, who wrote an essay and recently gave a talk to accompany the MOBIA exhibit, in which he points out some predominant themes in the posters: art, mysticism, magnificence, violence, and sexuality.

And indeed, to walk through the exhibit is to experience the entire range of Hollywood’s aesthetic—from tastefully artistic posters to politically-charged implications to tawdry depictions of fantastical epics. Though we might be tempted to think of Bible films as reverent, moral tales, fit for Sunday school viewing, the exhibit shows a movie business that has treated its source material in different ways.

Familiarity: The Greatest Story of All Time

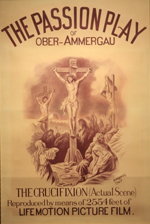

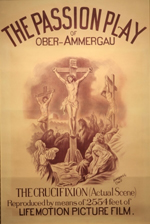

Many filmmakers, looking for gripping, relatable source material, naturally gravitated toward the life and death of Jesus. Early productions often borrowed the form of the Passion Play—a series of vignettes of the hours leading to Jesus’ crucifixion. This “genre” has its roots in educational and devotional practices of the church stretching back to medieval days—and in fact, by 1900, more than a dozen Passion Plays were filmed in Europe and the United States.

One of the most famous of these is the Passion Play of Ober-Ammergau, and its 1898 poster set the size for the industry “one-sheet” standard poster, making it the very first movie poster in existence. Under an image of Jesus on the cross, the poster proclaimed that this was “THE CRUCIFIXION (Actual Scene),” and that it was “Reproduced by means of 2554 feet of LIFE MOTION PICTURE FILM.”

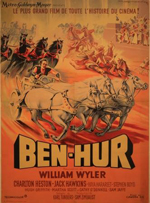

The life of Jesus offered an irresistible wealth of material, inspiring such films as King of Kings, The Greatest Story Ever Told, Jesus of Nazareth (with Robert Powell as a Christ with unnaturally blue eyes), Jesus (also known as The Jesus Film), and countless others. It also spawned the “sword and sandal” genre, which can be best thought of as spin-offs in which Jesus makes a guest appearance: Ben-Hur, The Robe, Sign of the Cross, King of Kings, and others.

Spectacle: Sex, Violence, and Enormous Sets

In 1928, the producers of Noah’s Ark took out a two-page spread in the New York Times, proclaiming, “NOAH’S ARK TAKES BROADWAY.” The advertisement spoke of a “colossal recreation of Deluge, crash of falling temples, tumult of war, human passions in eternal conflict … thrill after thrill—climax after climax—that outreach human imagination!”

That advertisement provided a foretaste of Hollywood’s reliance on spectacle to sell tickets to biblical movies. Part of the MOBIA exhibit is a scaled-down reproduction of a recently restored billboard poster for Cecil B. DeMille’s 1927 production of King of Kings, which features a scantily-clad woman wrapped in a red robe, riding in a chariot pulled by zebras with feathery red fans on their heads and driven by a buff soldier. Legions of people fall down around the chariot. One can only guess whether the actual “King of kings” will make an appearance in the film.

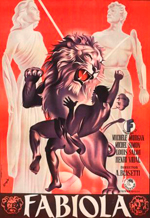

Later, some posters for movies such as Fabiola, Quo Vadis, The Ten Commandments, and The Sign of the Cross relied on the tantalizing promise of epic violence to interest the viewer. A surprising number also depended on sexuality, with posters for films such as The Silver Chalice featuring women in flimsy garb in the arms of strong, handsome men.

This is true even when the tale is ultimately one of redemption from a violent, promiscuous way of life. The Belgian poster for the 1955 retelling of the parable of the prodigal son (starring Lana Turner) depicts a lascivious scene, complete with fire, fleeing mobs, and what appear to be Vegas Showgirls. The American poster is the same—but uglier.

Politics: “A Retelling”

The Bible has been used as backing for many political groups, and unsurprisingly, movies based on Bible stories are often drawn into this function.

D.W. Griffith—who just a year before had produced Birth of a Nation, infamous for its positive portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan—made a film in 1916 called Intolerance, which presented a four-story narrative about tolerance and intolerance throughout history, using the life of Christ as its centerpiece.

Much later, Roberto Rossellini injected his 1975 film Il Messiah with a Marxist reading of the Gospels, which is drawn out in the French poster for the film, which uses the familiar workers-of-the-world-unite, power-to-the-people hand holding a hammer, but replaces the hammer with a cross.

Color of the Cross, a 2006 film, re-casts the crucifixion of Jesus as a racially motivated hate crime; the poster doesn’t intimate this theme—except for a link to blackchristianmovies.com.

The most interesting of the politically-motivated Bible movies is Cecil B. DeMille’s Sign of the Cross. Originally released in 1932, the film was re-released by DeMille in 1944—near the end of the Second World War—with an extra scene at the beginning of two Army chaplains flying over liberated Rome, talking about the martyrs who died there. The poster for the re-released film featured Allied planes flying in cruciform configuration over the burning city of Rome, and making a powerful implication about who was on God’s side.

Marketing: Dali, Warhol, and Group Sales

Today’s Hollywood movie posters often rely on vivid photographs of stars or familiar figures to trigger the audience’s interest. Movie studios have had a few extra tricks up their collective sleeve when marketing biblical films.

One effective way was to draw on familiar paintings to evoke a mood. For instance, the American poster for the 1920s re-release of The Passion Play explicitly quoted Heinrich Hoffmann’s 1980 painting, Christ in Gethsemane.

Later, the Czech poster for The Gospel According to St. Matthew echoed Salvador Dali’s surrealist painting, Christ of St. John on the Cross. The Italian poster for Rossellini’s Il Messiah, produced in 1978, uses a pattern of faces to echo Warholian pop art.

Marketing biblical films also presents an easy partner to movie studios: the church. One of the most startling pieces in the exhibit is a display of marketing materials for the 1959 Ben-Hur, which lay out in peppy detail a number of ways to increase the ticket sales for the movie by marketing to religious organizations.

What’s striking about these materials is their similarity to the way that Mel Gibson’s The Passion of The Christ approached the same group: glowing letters from religious leaders; sample letters to churches, school superintendants, and Catholic school administrators, explaining why Ben-Hur would be a valuable film for their parishioners and students; ideas for capturing airtime on TV and radio; and, of course, group sales. Movies might change, but Hollywood stays the same.

The Future of the Biblical Epic

Bible movies come in and out of style—John Huston’s failed 1966 film The Bible, for instance, killed the “sword and sandal” sub-genre. The MOBIA exhibit is strikingly lacking in any posters for the more mainstream Bible or Bible-based films from the past twenty years, such as Prince of Egypt and The Nativity Story, except for one for Gibson’s Passion.

One might wonder: do Bible movies have a future in the mainstream, outside of the Christian bookstore and on the silver screen? Or is the genre finally spent?

Father Morris thinks about this a lot, and points out that most biblical films to date have been produced by Roman Catholics and Jews. As a Catholic priest, he’d like to see more Protestants enter the fray. There are many more stories ripe for respectful but vibrant adaptation, and Morris is excited about the possibilities.

As Morris points out, the movies still present a way for cinemagoers to experience majesty and mystery in a powerful way. One thing is for sure: whatever form biblical movies take next, it will certainly be colorful. The posters don’t lie.

To see a slideshow of some of the posters in the MOBIA exhibit, click here.

All poster images courtesy of MOBIA, except Color of the Cross

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.