Pastor Johnny Murillo had often empathized with his congregation members at Christian Worship Center in Sacramento, California. But when one member came to his office during the 2006 Christmas season, panicked and desperate to keep his home from foreclosure, it hit too close to home.

“Dude, I know what you are going through,” Murillo told him. “There is a way out.”

He really believed there had to be a way out. The only problem was that at the time, he didn’t know what it was. Unbeknownst to anyone else, Murillo was also facing foreclosure. But not only was his house threatened: the church was struggling to pay its rent.

In California as well as a handful of other states, home foreclosure rates are spiking as prices slump. This fall, prices nationwide dropped 11 percent from one year ago, triggering a boom in distressed sales of single-family homes. In Sacramento, the situation is much worse than in other areas. Homes are selling for about 37 percent less than a year ago, and foreclosure rates are more than three times the national average. The Sacramento area has had 29,000 foreclosure filings since 2007, climbing to 3,640 in October 2008 alone.

Christian leaders around the nation admit they were not well prepared for either the burst housing bubble or the credit crunch. Nobody was, in fact. But many of them have discovered during this season of pain how the church as the body of Christ functions as an agency of last resort (even for its own clergy and members) in times of financial emergency. This seems to be about the only thing giving these leaders a new sense of hope.

“Like Job said, I came naked into the world,” Murillo says. His first father was an alcoholic drifter who was run over by a train. His next father was in and out of jail as a member of the Mexican mafia, and was murdered when Murillo was 11. Murillo and his brother joined a local gang, Barrios Libre Locos, before becoming believers. Then, Murillo told his brother, “We’re done with the gang thing—let’s lead our guys to Christ.” Several of the gang members eventually became pastors.

The young Murillo became a youth minister, and after 22 years of ministry planted Christian Worship Center, a church for Sacramento’s poorest of the poor. He and his wife received support from a San Jose megachurch, which connected them with a mortgage broker associated with World Savings Bank. Murillo and the broker were friends, and in 2003, Pastor Murillo leased a large structure for Christian Worship Center. One year later, Murillo went back to his friend to get a loan from World Savings to buy his first house.

A church plant in a poor neighborhood is not the surest of investments for a bank, but getting the loan was not a problem. And World Savings was offering flexibility: Murillo had options for making monthly mortgage payments. He could make a set minimum payment, pay interest only, pay as if it were a 15-year adjustable rate mortgage, or pay as if it were a 30-year adjustable rate mortgage. Murillo’s first minimal payments had an emphasis on minimal, since the initial rate was so low.

Murillo’s broker friend warned him about the dangers. The accruing interest could be higher than his minimum payments. If Murillo did not keep up, the unpaid interest would be added to the principal balance, resulting in dramatically higher payments down the line. (These types of loans, called “option ARMS” or “pick-a-payments,” were a hallmark of World Savings Bank, the country’s second-largest savings and loan before Wachovia bought it in 2006. In November 2008, the Justice Department announced that it had begun investigating whether Golden West Financial Corp., which ran World Savings, engaged in predatory lending.)

“My faith outweighed the dangers,” Murillo says. “We were full of faith and sold on refinancing.”

At its peak, the church plant gathered a congregation of 150. Murillo has a gift for plain talk, a lot of energy, and a strong, loving wife. People from the street had their lives turned around by God. Dozens of members got steady jobs, and through church-friendly brokers, many were able to buy their first homes, some members’ first steady shelter in years. Giving increased, and the Murillos were able to make the mortgage payments for their home and the rent for the church.

Soon, however, their loan adjusted and the first signs of financial stress appeared. “In June 2004, we bought our house with payments of $1,150 a month. That increased to $2,200 in 2006,” Murillo says. “Still, if the income of the church had stayed the same, we would have been okay.”

But many church members lost their jobs. “Three or four people lost houses. Then my neighborhood started having foreclosures every couple of houses.” By Christmas 2006, Murillo was deeply worried, but he kept it to himself. “It got me to the point that I was constantly thinking, How does a pastor make a buck?“

By June 2007, the pastor was making only partial payments, below the minimum, on his house. He was able to carry on through Christmas 2007, always expecting a miracle. But by January 2008, threatening letters and phone calls started coming. Bankers were adamant that there could be no adjustment to his loan.

“I talked to the bank, which had been taken over by Wachovia,” says Murillo. “They said, ‘There is nothing we can do.’?”

In fact, Wachovia was hearing the same pleas from countless borrowers like Murillo. It held $122 billion in such pick-a-payment loans—about 72 percent of its residential loan portfolio. In October, the bank said it had lost $23.9 billion in three months and was projecting another $26.1 billion in mortgage-related losses in 2009. Wells Fargo, which is in the process of buying Wachovia, said it expects to lose $32 billion in pick-a-payment loans once the deal goes through.

For a while, though, the loans were lucrative. Wachovia and other banks made billions by selling the New York banks a steady stream of complex, mortgage-backed investments that were split into multiple parts and repackaged with pieces from other loans.

‘WHY DO WE HAVE TO MOVE?’

At the bottom of the heap, beneath all the bank mergers and mortgage portfolios, lay Pastor Murillo, who was so deep in shame over his debt that he began wondering if he should take his own life.

“I was not only endangering our house but the Lord’s house, too,” he said. He was struggling to come up with enough money to buy every jug of milk. When someone left groceries on the Murillo doorstep, he was overcome with gratefulness and grief.

Throughout the spring, the church’s income kept plummeting. “We tried everything. We sold fireworks, cookie dough, you name it.” Finally, on June 11, 2008, Murillo stumbled up the steps of the Sacramento Superior Court to turn over his keys. It was the end of his home. He prayed it would not be the end of his ministry.

Murillo prayed, “Forgive me, God, for what I have done and not done.” In the spirit of Philippians 1:21 he prayed, “Let me live for Christ!” He earnestly wanted to live differently. “God, renew my mind so I will be wiser and lead my family and congregation better,” he prayed.

Murillo says his heart was convinced he needed to walk a new path. “I knew my way was not good business for the kingdom of the Lord.” But his mind was confused by hopes and responsibilities.

“I stood there, still believing for a miracle,” he said. “It never happened.”

The next day, the Murillo family was homeless. They fled to Nevada to live with relatives. The pastor looked around as they traveled by car. He looked at his wife, who told him, “We will be okay.” He looked at his three children, whom he had shielded from the ugly details. “It was the biggest break of my heart when our youngest asked, ‘Why do we have to move?’

“We were stripped down to our family, bobbing up and down in our car with our Lord. I shook off my shame and despair as I looked around. I realized that everything that mattered, everything that was eternal, was in that car right then. We go naked back to the Lord, clothed only with his righteousness.”

Murillo’s church turned its lease over to another congregation and now meets in a local Christian high school. The Murillos and other families in the church are renting homes. No one is homeless anymore. What the congregation has in common is tragedy—but also a newfound honesty and unity.

Pastor Murillo finally shared with the congregation all his secret heartaches and struggles that had led up to the disaster. He told them that they needed to dedicate themselves to teach others about pursuing righteousness in finances. When he told his full story, he was swarmed with expressions of relief from members who now knew that their struggles and heartaches were shared.

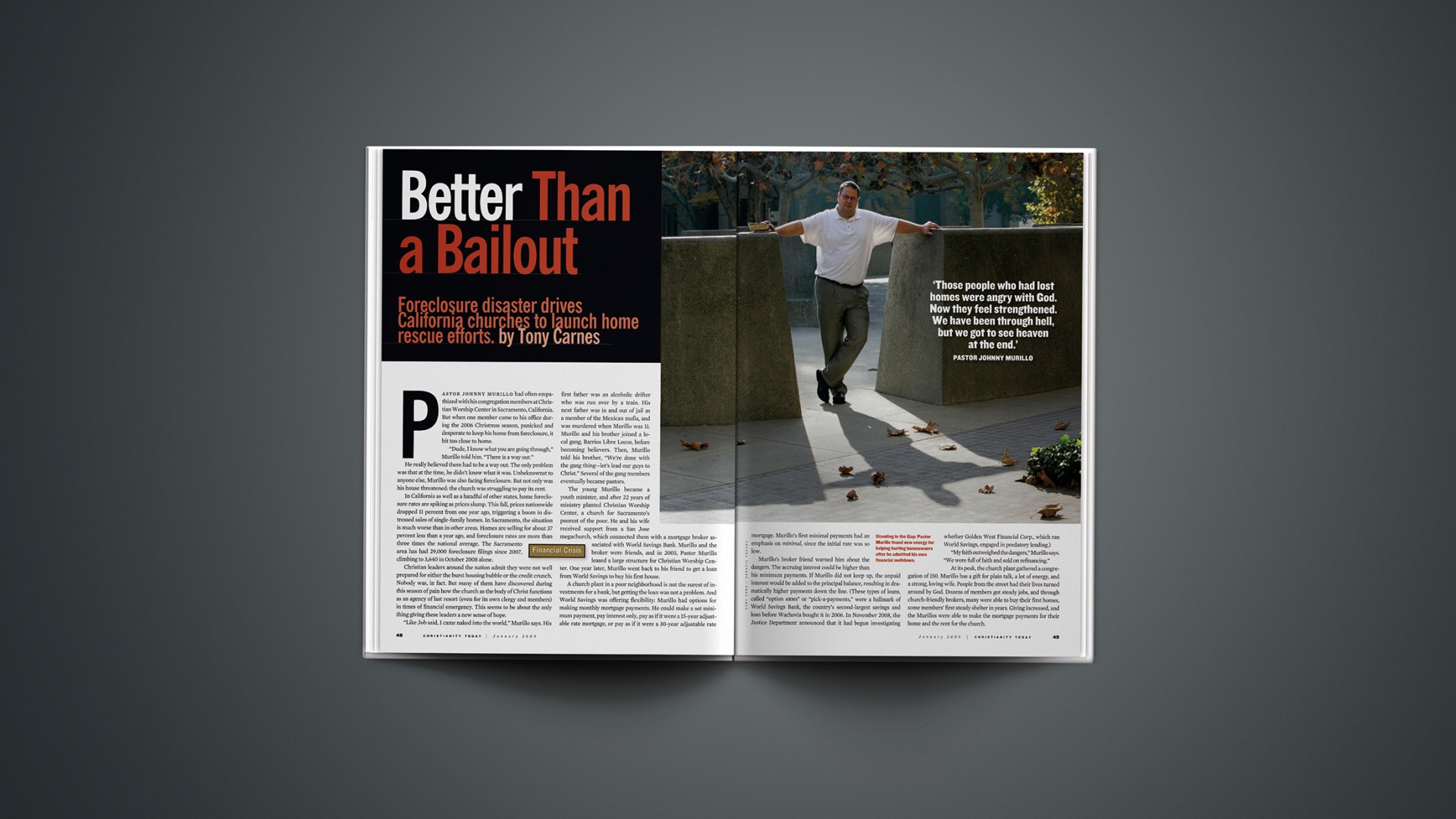

“Those people who had lost homes were angry with God,” Murillo says. “Now they feel strengthened. We have been through hell, but we got to see heaven at the end.”

LOST DREAMS IN SANTA ANA

In Santa Ana, a blue-collar town in Orange County, signs of economic collapse are still apparent. Lee de León serves as executive pastor of Templo Calvario, a Latino megachurch, while his brother Danny is senior pastor. The two take me down Camile Street, a typical residential neighborhood, and discuss the spiritual and financial lives of the homeowners.

“The homebuyers prayed about whether to buy in 2003, bought in 2004, and dedicated in 2005,” Lee says. At one point, these 1920s-era bungalows, set in pine trees with blooming bougainvilleas and green lawns, sold for as much as $650,000. Home values peaked in 2005 and have since plummeted by 50 percent or more.

Now Camile Street has one of the highest foreclosure rates in the country, tripling in less than one year. Rats scurry under the parched pines surrounding foreclosed homes. Lawns are ragged and home exteriors show obvious need of repair. Within earshot are policemen in hot pursuit of a suspect. Officers chase a young man and tackle him just around the corner on Baker Street. Gangs use the empty foreclosed houses as hideouts and party spots. Four people have been killed on this street within the past year.

Many of the families who lived in or owned these homes went through foreclosures in 2008, before banks set mortgage rescue plans in motion. Some families were homeless for a time, and are now either renting or living with family or church friends.

Lee remembers the spiritual dedication of many first-time homebuyers, the prayers of family members for their homes, and then the job stress and inability to meet mortgage payments as higher interest rates kicked in. In the past 18 months, the de León brothers saw the resulting shame and despair take root, leading to anger, bankruptcy, alcoholism, suicide, crime, and increased gang activity.

Until recently, the members of Templo Calvario, which meets in an industrial zone in Santa Ana, had no idea they were near the epicenter of a global financial crisis. Starting in late 2005, the crisis began with slowing economic growth coupled with rising interest rates, oil prices, and real estate values. But mortgages were still easy to get, and many homeowners still epitomized the American dream.

In 2004, many members of Templo Calvario were making their first home purchase. A few were buying homes as investments. They generally did not have the kind of credit histories that make bankers salivate, but an aggressive group of home loan agencies—Countrywide Financial, New Century Financial Corporation, Fremont Investment and Loan, and ACC Capital Holdings—had risen to specifically target Hispanic and African American first-time buyers.

Loan paperwork is almost always complex, but The Orange County Register and other reports say the loans to Templo Calvario’s parishioners and others like them were deliberately obfuscated. In some cases, borrowers were reportedly not told how rates would rise over the life of their loans. Loan officers told borrowers that they didn’t need a lawyer and often gave them misleading and false information.

The loan companies have either been closed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Company for corrupt lending practices or have paid more than $9 billion to settle allegations of fraud, forgery, and deception. These loan companies had many well-heeled partners in the investment world. Big banks in New York, London, and other financial centers asked few questions about billions in subprime loans. The finance industry repackaged these loans and sold them to investors, in turn making billions in commissions and transaction fees along the way.

Times were flush not only for the banks: A handful of early buyers in the church were able to “flip” their houses, selling them at a 100 percent gain.

“It was an exciting time,” says Lee. The economy was booming. The church was growing. People were being saved in record numbers. Real estate and loan agents inside the church promoted home ownership and church construction. Nearly 30 percent of the congregation took mortgage loans.

And so did the church. It seemed obvious that the church should jump into the buying spree. Templo Calvario is very active in community outreach, hosting three or more activities each day. So it expanded its community development corporation and launched a $9 million building and ministry campaign. Danny started building the new church and tended the flock, while Lee got the community development corporation humming. The brothers were absorbed in managing a complex enterprise, raising money and fighting City Hall over building permits. They say that they simply did not see the danger coming.

The de Leóns admit they and other church leaders started to take notice of the loan troubles in 2007. “A couple came to me because their [adjustable rate mortgage] was ballooning in costs,” Lee recalls. Soon, more people started showing up with their troubles. The church responded on a case-by-case basis, providing help with emergency food and shelter.

THE TRAP IS SPRUNG

When the housing bubble burst, federal regulators were most worried about inflation. For 2005 and 2006, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates in hopes that this would slowly cool off the economy. But by 2007, the American economy was souring quickly. Meanwhile, billions of adjustable rate mortgages were resetting to higher rates, triggering a cascade effect in the housing and financial industries.

The economy was going bad, but Lee says personal behavior—financial fraud and foolishness—were larger problems at his church. And, regretfully, Lee admits he and other pastors had their guards down. “We fell asleep at the wheel,” Lee said. “We can’t allow people to prey on our people. The mortgage people made a whole lot of money and victimized our people.”

The pastor points to a signpost of their slide into the trap. “In 2002, I stopped teaching our ‘manage your finances’ seminar because there was so much to do,” Lee says. “We stopped focusing on management of money.” Instead, the church’s focus was on raising money to buy real estate, especially residential real estate. Stewardship campaigns became more about fundraising and building than about prudence and minimizing debt. After all, church leaders reasoned, the good steward in Jesus’ Matthew 25 parable is the one who invested his five talents to reap five more.

“We were not balanced in our stewardship,” Pastor Lee says. “We talked to our members a lot about giving.” Just as the subprime mortgage sharks were developing myriad financial gimmicks to pump the enthusiasm and gullibility of their victims, the church developed financial expertise that would have won the admiration of Wall Street.

“We had all kinds of ways to give,” he said. “What we didn’t do was teach how to manage money.”

De León finally spotted a red flag when a mortgage broker in the congregation came to him with the opportunity to free up money for Christian ministry by refinancing Lee’s house. The pastor became suspicious when he could not understand the broker’s complicated explanation of a “tremendous opportunity” that would cost “almost nothing out of pocket.”

“It sounded too exotic for me. I wanted plain and simple, and what I got back was too out there,” Lee says. But the deal making continued inside the church as two or three brokers worked with 15 others to bring fellow congregants into complex refinancing deals. Pastor Lee’s nephew bought into the scheme and is still struggling to keep his home.

Templo Calvario has 5,500 members in 1,200 families. Up to 30 percent of the congregation has purchased homes since 2004. Of that 30 percent, the majority had adjustable rate mortgages, balloon payment loans, escalating interest loans, jump interest loans, no down payment loans, no principal payment loans, negative interest loans, or secondary and tertiary refinancing. In theory, each of these kinds of loans could be a good investment. But generally speaking, they were a bad idea for the families at Templo Calvario.

The de Leóns estimate that 90 percent of the families with suspect loans, about 300 families, might lose their homes. Another 200 families are barely holding on due to other economic hardships.

The brothers are confident that Templo Calvario will survive and thrive again. They are determined to be a leading advocate for financial education within the Latino community.

RESCUES GATHER STEAM

After surviving financial storms, pastors at the center of the foreclosure crisis say they have learned lessons about practical theology, the responsibilities of the church, and pastoral leadership.

“We stayed away from members’ whole financial world,” Pastor Lee says. “We didn’t see this financial stuff as ministry, and dropped it.”

In northern California, Pastor Eva Rodriguez, a friend of the Murillos’, put it this way: “We should have been more aware. But our church has been put in a box by theology and Hispanic culture, where you are not allowed to talk about finances.”

Some churches that had financial seminars turned them over to their own financial people in the congregation. But these churches often did not vet volunteers to separate those honestly eager to help from those eager to expand their client base through the church. It’s worth remembering that the rain falls on the just and unjust alike. “Our method of setting up classes raises a question. Some of our own bankers bought into that stuff themselves,” Pastor Lee warns.

As one banker with Countrywide Financial told me, “I just didn’t see the problems on the horizon. I bought my home and two rental condos and have lost them all.”

Hispanic pastors are hoping to pool the lessons they have learned. Through the Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference they are drafting a three-point plan to address the crisis:

- Work proactively with affected families, banks, and mortgage companies to expose fraud.

- Create a formula to help prospective home buyers detect and avoid problem loans.

- Start a charitable fund to help families and churches that have lost everything.

The churches might take notes from a predominantly black church in Queens, New York. Bethel Gospel Tabernacle of South Jamaica sits at ground zero of the Northeast’s mortgage meltdown. There are more foreclosures and homes close to foreclosure there than anywhere else in NYC. Yet out of 2,000 Tabernacle church families (a number of whom have members who work on Wall Street), fewer than five succumbed. Why?

Tabernacle’s Bishop Roderick Caesar is far from conventional. “The church needs to grow people with faith and habits in their bones, not two-hour-per-week Christians,” he says. Caesar preached a mini-sermon against subprime mortgages during every sermon on every Sunday for ten years.

The congregation can recite by memory Caesar’s four-point credo for the use of money:

- Tithe and pay your bills on time.

- Save systematically and invest.

- Spend wisely and responsibly within your means.

- Don’t buy what you don’t need.

Bishop Caesar is preparing church members to help individuals financially adrift in the flotsam of lost dreams. “We in the church must gather the down-to-your-bones Christians and launch out in rescues.”

A similar rescue outreach is gaining momentum in Southern California. It combines elements of evangelism and financial service. Here’s Life Inner City of Los Angeles is developing a partnership with 120 churches called FAITH: “Foreclosure Assistance in the Hood.” The ministry provides lists of foreclosures around a church and trains church members to visit each family in the foreclosed or soon-to-be foreclosed home with offers of prayer and financial counseling seminars at the church.

FAITH director Ken Frech says most people in the Los Angeles area don’t see the church as a place to turn when foreclosure looms. They only come to the church after they are on the street.

“People say, ‘How is the church relevant to our situation?’ But we can bring a radical Christianity that goes to the spiritual roots of the people’s catastrophe,” says Frech.

In Santa Ana, the de Leóns are planning seminars for Hispanics in danger of foreclosure. Such events will involve the major banks, mortgage companies, Christian financial counselors, and attorneys. The church is working with a team of reliable real estate people to keep out mortgage sharks. Pastor Lee says their credibility will be based on a new reality: “We have gone through it and have turned our lives around with Christ.”

Tony Carnes is a Christianity Today senior writer living in New York City.

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today has a special section on the economic crisis.