The sun was setting as our small bus bumped along a Vietnamese highway. Then someone began to sing. We were in the middle of a four-hour drive between Buon Me Thuot and Pleiku, having just endured a day of formal meetings with government and church officials, meetings as necessary and exhausting as tilling a garden that has been long neglected.

The singer was our guide, Hoang Cong Thuy, secretary general of the Vietnam-usa Society, an organization with close ties to both the Vietnamese Communist Party and the government. The cliché “he is a small man with a big heart” was invented, I’m sure, after someone met “Mr. Thuy” (as he is called). Unfailingly cheerful, even though he had to endure the quirks of eight evangelical pastors, three businessmen, one nonprofit diplomat, and one skeptical journalist, he worked to keep our spirits up. So during our drive, he grabbed the microphone of our little bus and began belting out a Sinatra tune. A cappella.

It was a joyful noise, as one is wont to say about earnest musical efforts. And it inspired equally modest talents on the bus to join in. One of our party—a man in his retirement years—gave a rendition of Elvis, followed by a bold fellow crooning from the repertoire of the Monkees. Then the Vietnamese sang their national anthem, and we followed with ours.

As Amy Rowe, one of the intrepid travelers, wrote in her blog, “It doesn’t get any weirder than Baptists and Communists singing karaoke together in a van driving through the middle of Vietnam.”

Yes, but weird stuff like this is at the heart of religious freedom efforts in Vietnam. It is the sort of thing that is making a difference for Christians there.

Emerging World Player

I went to Vietnam in late August and early September 2006. The Institute for Global Engagement (IGE) and the Vietnam-USA Society (VUS) organized the trip. VUS is a part of the Fatherland Front, an umbrella of pro-government organizations overseeing many government programs and policies, such as religion policies. The trip was part of an agreement—formally called a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)—between the two parties, saying that American pastors and scholars would visit Vietnam “to better understand religious freedom challenges and progress.”

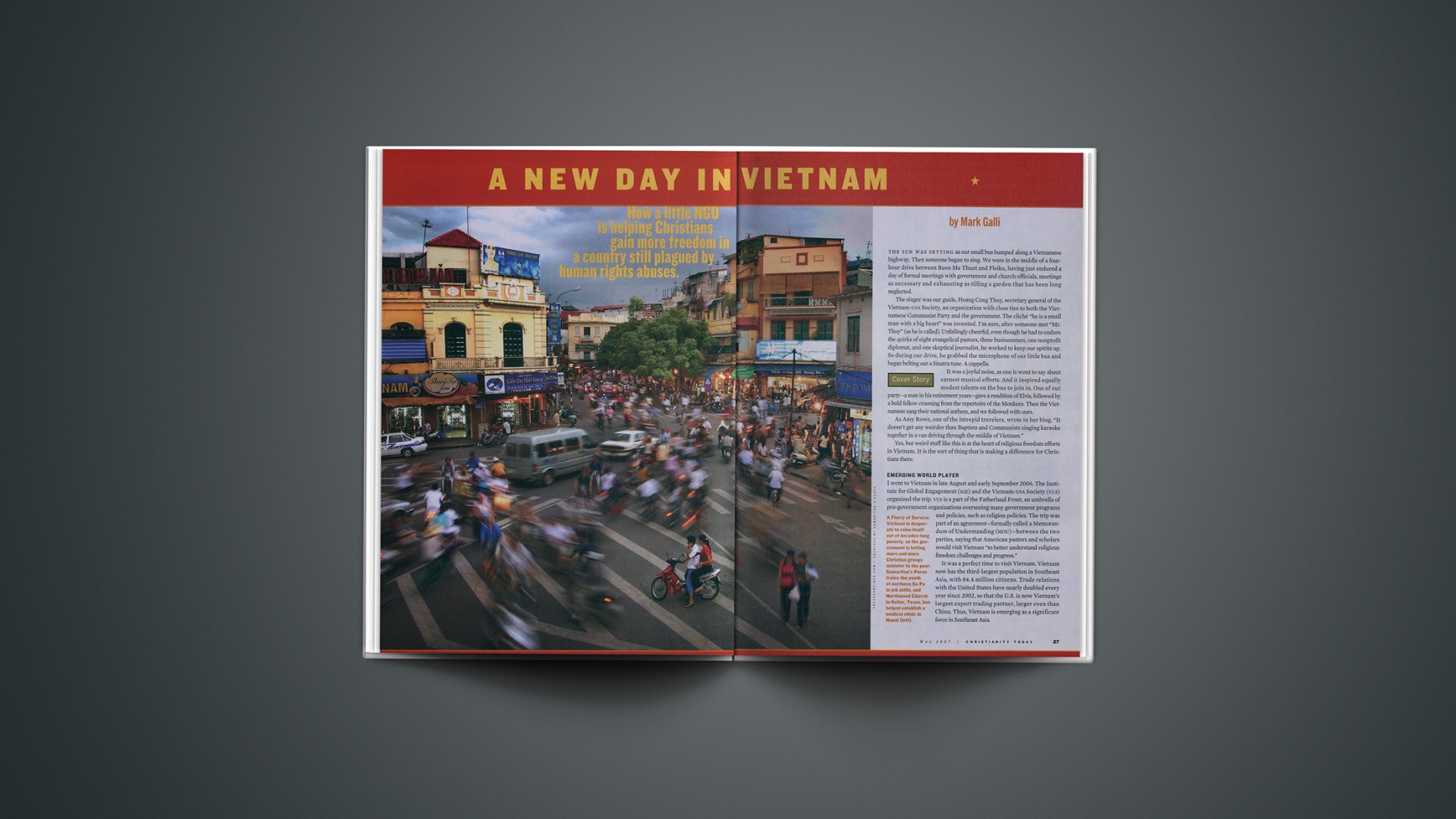

It was a perfect time to visit Vietnam. Vietnam now has the third-largest population in Southeast Asia, with 84.4 million citizens. Trade relations with the United States have nearly doubled every year since 2002, so that the U.S. is now Vietnam’s largest export trading partner, larger even than China. Thus, Vietnam is emerging as a significant force in Southeast Asia.

In addition, a variety of forces were at play last fall. The country has had an atrocious human-rights record since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. It has also had an atrocious economy. Both atrocities were perpetuated by an unswerving, ideological commitment to communism. Human rights abuses had led to various international sanctions. The U.S. had listed Vietnam as a Country of Particular Concern for its religious freedom abuses. That, in turn, had blocked Permanent Normal Trade Relations status, which Vietnam needed to clear the way for U.S. support for accession to the World Trade Organization. Economic isolation had stalled the economy.

But in the 1990s, Vietnam’s rulers began making significant reforms, somewhat along the lines of Communist China, trying to combine political socialism with a liberalizing economy. While Vietnam was trying to get in the good graces of the U.S. and the WTO, it signed an MOU with IGE, a faith-based organization that “promotes sustainable environments for religious freedom worldwide” through “relational diplomacy.” Its work in Vietnam may be the most significant example of how the U.S. and global evangelicals can better expand religious freedom in repressive states.

So the 12 of us found ourselves in a bus with bad shocks and whistling windows, headed for Pleiku, singing like fools. As we were discovering, there was something to sing about: The religious situation in Vietnam is indeed new.

The Bad Old Days

Five years earlier to the month, in the very province we were driving through (Dac Lak), police summoned N. (name withheld by Human Rights Watch investigators). He was badgered with questions: Who were the members of his church? Why did he teach the Bible if he was not a pastor?

At one point, the interrogator, Mr. H., cursed N. and said he was stupid: “So you believe in God? Have you ever seen him? What has God given you? Has he given you money? Have you borrowed money from the bank? God hasn’t given you anything at all, but the state lets you borrow money, the state builds roads, the state gives you electricity!”

Such harassment was common in 2001. But in some places—such as Gia Lai, the district we were heading toward—things were brutal. On March 9, 2001, hundreds of soldiers and riot police surrounded and then entered the village of Plei Lao. They wore white helmets and protective padding; they carried shields, batons, electric truncheons, tear gas, and guns, arriving in jeeps and army trucks. The government had decided to do something about a prayer meeting of more than 500 Christians from the area.

A villager who tried to warn the Christians was handcuffed and thrown into an army truck. His sister, along with other villagers, pleaded for his release, but “the police beat the sister until blood came out of her MOUth,” an eyewitness told hrw. “They hit her with an electric baton and with their fists.”

When villagers tried to fight back, the police fired tear gas into the crowd and started beating people. “Many people ran,” said the eyewitness. “Then the police lowered their guns and fired at the people running away.”

The police ordered some villagers to destroy the church with axes and burn it down. “Afterwards,” the eyewitness concluded, “the police put fresh earth over the ashes and smoothed it so outsiders could not tell there had ever been a church there.”

Five Years Later

“The church here is enjoying very, very good conditions,” the pastor said. “We have about 120,000 Christians, 310 chapters [congregations], and about 226 full-fledged pastors. We are different nationalities, but we are living as brothers in unity and harmony.”

One of four Dac Lak pastors was speaking about the church in his district. We sat in one pastor’s house, in a long room that had been converted for church use, on folding chairs around folding tables. A neon church sign glared at us from one wall. It was almost five years to the day since N. had been summoned by police in the same district.

The pastor said they hoped to build four churches in the coming months. Bob Roberts, pastor of Northwood Church in Keller, Texas, who had organized the pastoral delegation for IGE, was intrigued. Roberts asked about the size of the pastor’s church. The pastor replied that his was a small one, with only 500 followers.

Roberts pointed to another pastor and asked the translator, “How many go to this man’s church?”

“Eight hundred and seventy.”

“And how many go to his church?”

“Two thousand, four hundred, and sixty.”

The eyes of the American pastors widened. Roberts just beamed. He is a church-planting guru for thousands of U.S. pastors. After pausing to take it in, he said, “Ask them if they would come to America and teach us to grow our churches!”

Indeed, Dac Lak, a center of persecution just a few years ago, is now a center of church growth. The Vietnamese government can’t keep up. The chairman of the Dac Lak Religious Affairs Committee, in another meeting, told us there were 100,000 Christians in the district. The disparity in figures was the same nearly everywhere we went. Government officials always cited lower figures than did church leaders. No doubt self-interest tempts each group to adjust its figures. But even the government admits that the church is growing rapidly, as it has been for decades.

In Dac Lak, Human Rights Watch estimated that Protestant churches had grown from less than 12,000 in 1975 to more than 87,000 in 1999. If the pastor’s estimates were correct, the area had experienced another 40 percent jump since that time.

Such growth, reported elsewhere in the country, is wonderful, but Protestants still account for less than 1 percent of the population. There are about 800,000 Protestant Christians in Vietnam, according to the government; about 1.6 million, according to church leaders. The government similarly pegs Roman Catholics at 5.3 million, while Catholic leaders go as high as 8 million, which would be nearly 10 percent of the population.

In addition, for the last year or so, officials have been pushing to increase the number of officially registered churches (to make them legal entities, affording them certain protections). By June 2006, Dac Lak authorities had agreed to register 38 churches. By the end of the summer, that number was 45. This is lightning speed for a bureaucratic, Communist government. We saw the same sort of jump in every area we visited.

“That’s really impressive,” Amy Rowe, director of country programs at IGE, told Dac Lak officials. “We’re very, very encouraged. And I know that the people in Washington, d.c., are very encouraged by the progress being made in Dac Lak province. This is very good news.”

Small. Young. Influential.

The size of IGE’s staff (six full-timers) and the scope of its work (focusing on only five countries) make it absurd to think that IGE would wield much influence in d.c. But in its short history, IGE has become the little nonprofit that could.

That’s partly due to a professional, efficient, and dedicated staff that gets two weeks of work done every seven days—week after week. But it’s also due to its leaders.

I met founder Robert Seiple at an IGE board meeting in November. He’s in his 60s, and he appears to be a mellow, congenial fellow at first meeting. He is that and more. My wife and I sat down for coffee with Seiple and his wife one morning after I’d made a presentation the night before. The first thing he said was, “I disagree with what you said last night.”

I’ll admit to feeling intimidated. Seiple founded IGE in 2000 after spending two years as the first U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom, a position created by the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998. He was charged with promoting religious freedom worldwide and making sure that this issue was woven into the fabric of U.S. foreign policy. In addition to stints as president of World Vision (11 years) and president of Eastern University (4 years), in the late 1960s he served in the U.S. Marine Corps, attaining the rank of captain. He flew 300 combat missions in Vietnam and was awarded 5 Battle Stars, the Navy Commendation Award with Combat ‘V,’ 28 Air Medals, and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Seiple is not someone you want to tangle with. He has little patience for shallow or short-sighted thinking—but neither would he respect someone who just wilted before him. He quietly gave his reasons for dissent, I stood my ground, and we soon moved to other matters. It wasn’t personal for him, just an important point to engage.

It is clear that Seiple has imbued the young IGE with tough-minded political realism, compassion for the religiously oppressed, and a commitment to relationship diplomacy. His son Chris is the current president, and the acorn has not fallen far from the tree.

A Stanford graduate, Chris served as an infantry officer in the Marines in the 1990s. His last assignment was in the Pentagon in the Strategic Initiatives Group, an internal think tank for the commandant of the Marine Corps. During those years, he advocated a new national infrastructure for the post–Cold War world. This past February, he earned his Ph.D. from Tufts University, with a dissertation on U.S.-Uzbekistan relations.

I met Chris in Vietnam, when he joined our party for the second week of the trip. We were sightseeing for a day, and he sat next to me on the bus. He started off our first conversation by telling me what was wrong with Christianity Today. Like father, like son.

Many voices today are shouting on behalf of religious freedom through op-ed pages and think-tank declarations, framed in angry rhetorical flourishes that “demand immediately” that someone do something. That something usually amounts to sanctions of one sort or another and a refusal to deal with the repressive regime until it gets its act together.

IGE believes, instead, that religious freedom begins in the heart of “difficult places” (an operative phrase at IGE) with conversations with government officials. Like his father, Chris (who still has that chiseled Marine look) is no touchy-feely peacenik who bends justice so everyone can get along. He has regular contact with the State Department and has testified to Congress about religious freedom in Vietnam. He’s someone who commands respect. He will tell you the truth. He will keep his word. And he doesn’t blink.

The fall trip to Vietnam was designed to end with the signing of another Memorandum of Understanding. So during the trip, Chris, with Rowe’s diligent assistance, negotiated with Vietnamese authorities about the new MOU’s wording. As the trip hurtled to a close, the Vietnamese arranged a signing ceremony, alerted the press, and planned festivities. A few hours before the signing, Chris was shown a “final” draft of the MOU. He said the language in one section was still not strong enough, and he wouldn’t sign it until that changed. High stakes, indeed. But IGE and VUS managed to hammer out an agreement before the ceremony began.

I later told him that many people would not have risked leaving Vietnam without another MOU—it would have made IGE and the entire trip look like a failure.

Chris replied, “We would have failed if we had signed an agreement that didn’t have teeth in it.”

Cultural Complications

Chris is humble and realistic enough to know he’s only one part of a complex human-rights ecosystem. It needs hard-hitting op-ed denunciations as well as effective government sanctions. And he doesn’t hesitate to use that leverage, but he mostly uses the strong relationships he has painstakingly built. Consequently, the latest MOU establishes an annual scholars’ conference on religion and rule of law (one was held in September 2006 as part of the first MOU), partnerships between Vietnamese and American communities to promote socioeconomic development, “exchanges of analysis on religious discrimination reports,” and “dialogue between governmental and religious representatives on Vietnam’s religious freedom laws.”

For a Communist country that five years ago was breaking up prayer meetings and shooting into crowds, this is extraordinary. The freedom of people “to choose or not choose their religion” has been a part of the Vietnamese Constitution for some time, but the government is only now getting around to enforcing that ideal—thanks to forceful op-eds, government sanctions, and the patient, relational work of IGE.

No, Vietnam has not suddenly blossomed into a liberal democracy. A quick Google search for “Vietnam persecution” reveals plentiful examples of ongoing human rights violations, some of them brutal. Thus the need for continuing “dialogue between governmental and religious representatives.”

Yet nearly every case of religious repression I have investigated since my trip involves Christians advocating democracy. This by no means condones the government’s terrible repression of political free speech. But it says that Vietnam—its government and people—is deeply and mainly concerned about political unrest. The nation was at war for half of the 20th century. Like other totalitarian governments, Vietnam’s administration quickly becomes anxious about groups that advocate political change. Much of the persecution in 2001 was grounded in this fear, and government officials, often tone deaf to religion, have struggled to discern which religious groups advocate democracy and which do not. Those that do are treated harshly.

I asked one of the pastors in Dac Lak about repression. “We live a normal life,” he said. “But there have been a number of bad elements instigating the people to do some evil.” That is, some—Montagnards or Dega Christians—push for democratic reforms. “But here, the Christian followers have respect for the governing officials. Everyone needs to abide by the law. And every Christian needs to pray for peace, so that we can enjoy the freedom to worship in the service of God, and so we can pass on the faith to other people.” This sounded like a speech coached by the government, but it was something this man really believes.

In a formal meeting in Hanoi, I asked the vice chairman of the Committee for Religious Affairs, Nguyen The Doanh, about a pastor in Ho Chi Minh City whose church had reportedly been closed by police officials. As soon as the translator mentioned the pastor’s name, the official shook his head and sighed.

“I met him last month and had a dinner with him,” he said. He wanted to tell the man about the new church registrations policy. “[But] I must say that under the terms of the governmental management, he’s not recognized as a pastor.” Actually, Doanh continued, he doesn’t have a church, but people merely meet in his home. So the government could not have “shut down his church.” The problem with this man, he said, is that he is an “extremist”: “He was trying to dismiss one traditional belief of the Vietnamese people. Why does he need to tarnish other religions, insulting the belief of the Vietnamese people?”

Apparently, the pastor had criticized the cult of the dragon, a symbol of supernatural power and blessings.

“He insulted it,” the vice chairman continued. “The dragon is a holy symbol of the people and the ruling spirit of the Vietnamese people. So everywhere he goes, he is opposed by the people, by the community.”

I later questioned Vietnamese Christians about the case, and they didn’t disagree with the vice chairman’s assessment that the pastor is “a man who is always losing his temper, unstable in personality.” Whether or not this particular assessment is accurate, it is clear that one cannot take all persecution reports at face value. Sometimes Christians get in trouble for cultural insensitivity.

But neither should we take government explanations at face value. I asked the same official about the 2005 closing of New Life Fellowship, an international church in Ho Chi Minh City, and he acted like he hadn’t heard of the incident and promised to look into it. A confidential and highly respected source on Vietnam told me the Committee for Religious Affairs “played dumb. … That is ultimate disingenuousness! They are involved up to their eyeballs!”

The government has a way to go. Still, some cultural tensions cannot be easily solved. A typical scenario told to me by more than one official: A Vietnamese man becomes a Christian. He refuses to offer sacrifices to his family ancestors any longer. His father dies, and his brothers claim the family property, excluding the Christian because he has essentially disowned the family. The Christian sues and demands his rights as a son. This is just a small consequence of religious freedom that the government has got to get used to.

Another problem, which the deputy director alluded to, is bureaucracy and human nature. A central government decree ordering respect for religious activity isn’t necessarily going to be obeyed by local officials far from the capital. Especially if the policy is a change and local officials have yet to be trained in its nuances.

A New Paradigm

So when working for religious freedom, one cannot simply shout “persecution” from the rooftops and ignore the complex social and political situation. This is where IGE shines.

I asked Chris Seiple what sustainable religious freedom looks like. “It has two dimensions,” he said. “One, religious freedom is legally protected. Two, it is culturally owned. Culturally owned means the people who live there understand that this is in their self-interest, and they contextualize the principle [of religious freedom] to a pre-existing principle that’s already in their culture.”

Seiple gave an example from Vietnam. Government officials have been reluctant to allow seminaries to be built. His response to them has been, “Seminary is security.” He argues that if they don’t encourage the church to have theologically trained Christians who can educate their flocks, those flocks are open to being hijacked by extremists who can create social unrest. The argument makes sense to officials and allows churches to work their spiritually liberating influence on society quietly—like the early Christians did in the Roman Empire.

Thus, IGE works from the top down (with high government officials) and from the bottom up (with local churches and other religious bodies). Freedom is not going to last without engaging all sectors of society, as embodied in the September trip.

Besides singing karaoke, this type of religious freedom work requires the stamina to endure long-winded, boring speeches by controversy-averse officials. It means having to sit through mind-numbing scholarly presentations, hour after hour, on religion and the rule of law. It means sharing cups of tea with government officials, professors, and pastors—asking them about their families, their lives. It means sitting down to dinner with officials, eating exotic foods with apparent pleasure and drinking toasts to one another long into the night. (The toasts presented a particular challenge for some of our teetotaling Baptist pastors, who felt culturally obliged to partake—and then warned me that the Baptist mafia would be after me if their names came out.) All this makes possible private, frank conversations with government officials that begin to shape attitudes.

In short, IGE is practicing a new paradigm in advocating for religious freedom. The Cold War model of many organizations has been covert support for oppressed Christians combined with outsider advocacy. In the early years of the 21st century, IGE is flipping this model on its head: open support for Christians and insider advocacy.

The Vietnamese are still trying to maintain control, hamfistedly at times, while recognizing the need for more freedom. But as Le Hoai Trung, a deputy director in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, put it, “On our part, we’re not saying that we are error or mistake free. That is why we very much want to improve things, and that is why lately the government has sent out instructions—a decree to make sure that the government at different levels abides by the laws [already on the books].”

Furthermore, the Vietnamese, like most Asian cultures, emphasize community and stability. Westerners exalt the individual. It’s hard to imagine that a culturally grounded religious freedom in Vietnam will ever mimic the U.S. model.

Still, Vietnam’s religious landscape has brightened. The United States government late last fall revoked Vietnam’s status as a Country of Particular Concern and granted it Permanent Normal Trade Relations, which in turn paved the way for Vietnam’s acceptance by the WTO. Now the country has an opportunity to jump-start its economy.

Naturally, the question for the future is: Will Vietnam abandon its stated commitments on the religious side? The recent crackdown on human rights and democracy advocates (see caption above) gives one sobering pause. But no one said pursuing justice was a cake walk—certainly not IGE.

Mark Galli is managing editor of Christianity Today and the author of many books, including Jesus Mean and Wild: The Unexpected Love of an Untameable God (Baker, 2006).

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

“Chris Seiple on ‘Relational Diplomacy’” and “Inside CT: Graveyards Came First” accompanied this article.

Vietnam was taken off the US State Department’s list of Countries of Particular concern in 2006, but the USCIRF urged that the country be put back on in its most recent report.

The Institute for Global Engagement‘s section on the fall 2006 relational diplomacy in Vietnam has press releases, articles, an op-ed on constructive advocacy, and a trip blog.

Other Christianity Today articles on Vietnam are available on our site.

Christianity Today articles featuring the work of IGE include “Living with Islamists” and “Love Your Muslim as Yourself.”

IGE founder Robert Seiple has contributed to Christianity Today on topics including international relations and persecution:

Madam Reverend Secretary | With the publication of The Mighty and the Almighty (Robert Seiple, June 29, 2006)

The Dick Staub Interview: Robert Seiple on the War in Iraq | The founder of The Institute for Global Engagement says America suffers from an inconsistency between national values and national interests. (April 1, 2003)

The USCIRF Is Only Cursing the Darkness | The increasingly irrelevant U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom seems intent on attacking even those countries making improvements. (Robert A. Seiple, October 1, 2002)

Also: USCIRF’s Concern Is To Help All Religious Freedom Victims

Religious Liberty: How Are We Doing? | The challenges of being an international cop for human rights—a report by the first U.S. ambassador at large for religious freedom. (Robert Seiple, October 22, 2001)

De-Seiple-ing World Vision | Straight talk from Bob Seiple on myopic Americans and the new realities facing international development. (June 15, 1998)

Clinton Names Seiple to New Post | President Clinton named former World Vision president Robert A. Seiple to the new post of senior adviser for international religious freedom. (July 13, 1998)

De-Demonizing the UN | While bloated and badly in need of reform, the UN fills a necessary role that Christians should support. (Robert A. Seiple, December 11, 1995)