| • |

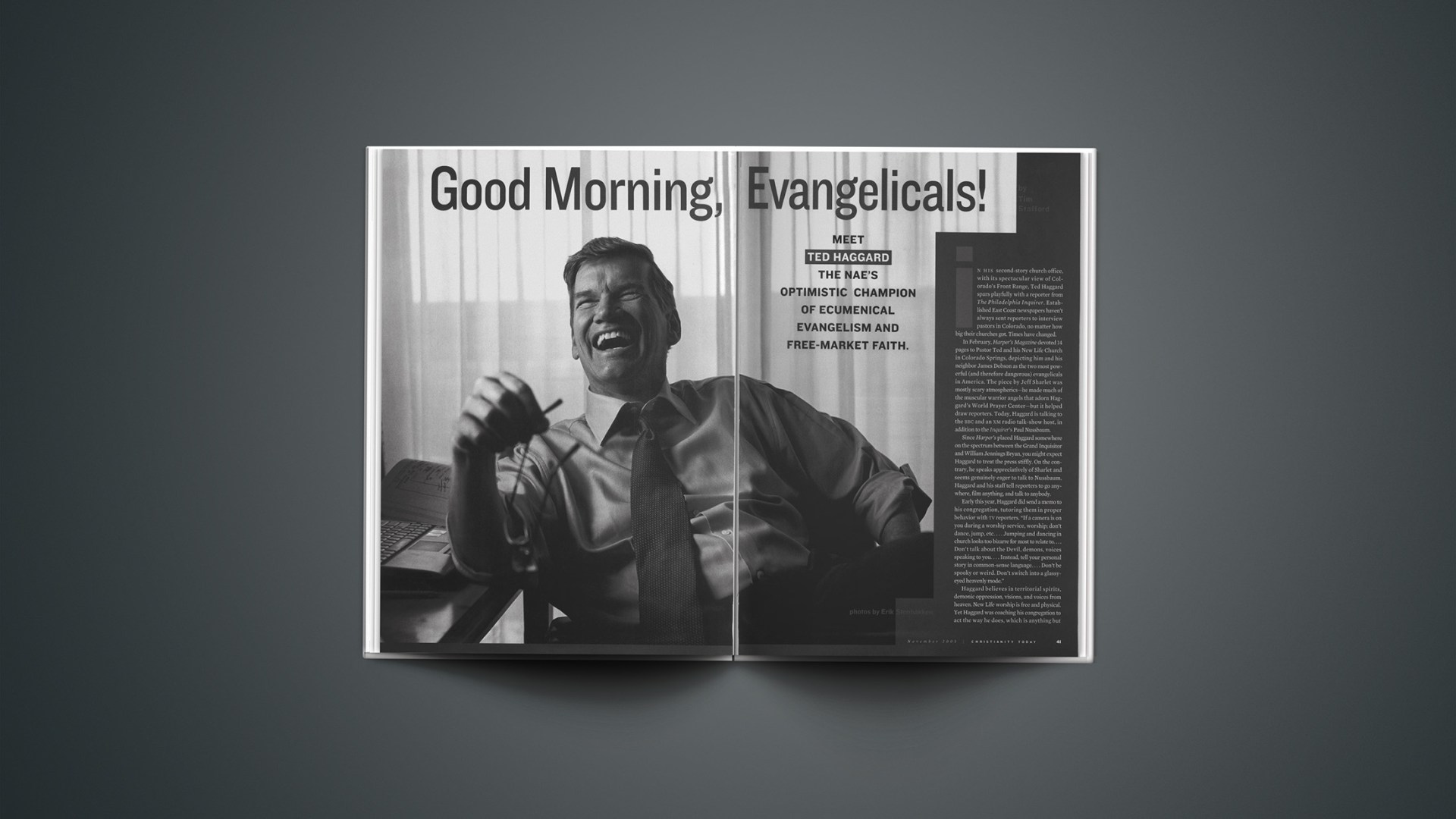

In his second-story church office, with its spectacular view of Colorado’s Front Range, Ted Haggard spars playfully with a reporter from The Philadelphia Inquirer. Established East Coast newspapers haven’t always sent reporters to interview pastors in Colorado, no matter how big their churches got. Times have changed.

In February, Harper’s Magazine devoted 14 pages to Pastor Ted and his New Life Church in Colorado Springs, depicting him and his neighbor James Dobson as the two most powerful (and therefore dangerous) evangelicals in America. The piece by Jeff Sharlet was mostly scary atmospherics—he made much of the muscular warrior angels that adorn Haggard’s World Prayer Center—but it helped draw reporters. Today, Haggard is talking to the BBC and an XM radio talk-show host, in addition to the Inquirer‘s Paul Nussbaum.

Since Harper‘s placed Haggard somewhere on the spectrum between the Grand Inquisitor and William Jennings Bryan, you might expect Haggard to treat the press stiffly. On the contrary, he speaks appreciatively of Sharlet and seems genuinely eager to talk to Nussbaum. Haggard and his staff tell reporters to go anywhere, film anything, and talk to anybody.

Early this year, Haggard did send a memo to his congregation, tutoring them in proper behavior with TV reporters. “If a camera is on you during a worship service, worship; don’t dance, jump, etc. … Jumping and dancing in church looks too bizarre for most to relate to. … Don’t talk about the Devil, demons, voices speaking to you. … Instead, tell your personal story in common-sense language. … Don’t be spooky or weird. Don’t switch into a glassy-eyed heavenly mode.”

Haggard believes in territorial spirits, demonic oppression, visions, and voices from heaven. New Life worship is free and physical. Yet Haggard was coaching his congregation to act the way he does, which is anything but spooky or weird.

“He doesn’t carry Pentecostalism as a chip on his shoulder,” notes Pentecostal historian Vinson Synan. Jack Hayford marvels at how naturally Haggard expresses himself in terms that appeal outside the evangelical community. “I have to work to think, How can I say these things? This stuff just flows out of Ted.”

Who Is an Evangelical?

“When I became president of the NAE [National Association of Evangelicals],” Haggard tells the Inquirer‘s Nussbaum, “the talk was about doing away with the term evangelical. Evangelicalism was morphing and changing so much that people were wondering if the term applied. The first decision I made as president was to start using the term prolifically and defining it simply. I define an evangelical as a person who believes Jesus Christ is the Son of God, that the Bible is the Word of God, and that you must be born again.”

Haggard, who is 49 but looks younger, with sandy hair and eyes that squint when he grins, goes on to explain that the 2004 presidential election has increased popular interest in the evangelical movement.

“Is it correct to say ‘values voters’ are evangelicals?” Nussbaum asks.

“Yes.”

“Because, by your definition, Jimmy Carter is an evangelical.”

“He is.”

“Bill Clinton?”

“He is an evangelical.”

“Hilary Clinton.”

“No, she is not.”

“So, which of these definitions doesn’t she meet?”

“I’m not going to say.”

Nor will he budge from that reticence, though Nussbaum gently badgers him. Haggard loves to talk, and Nussbaum has caught him making an off-the-cuff pronouncement he is unwilling or unable to substantiate. Yet Haggard seems about as chastened as Huck Finn apprehended with Aunt Polly’s strawberry jam. Rather than becoming frosty or severe, Haggard surges forward into his topic.

“Evangelicalism is a continuum of theologies all the way from Benny Hinn to R. C. Sproul. The R. C. Sproul crowd has a hard time with Benny Hinn, and the Benny Hinn crowd has a hard time with R. C. Sproul. But they’re all evangelicals.

“Evangelical does not mean any particular political ideology,” Haggard continues. “The African American [evangelical] community has an honorable concern for social justice, and that affects their politics. That concern comes from the Scripture. The Anglo community has a different history, so different Scriptures stand out to them. To the Anglo [evangelical] community, most of their sermons are theological. It’s salvation by grace through faith, and other theological points, so social-justice issues don’t have the same compelling justification.

“I have a deep love and appreciation for that diversity. I think it’s some of the wonder of the body of Christ. I feel like my role is to help the various members of the body respect one another and appreciate one another, and work together.”

Changing Evangelicals

While much press attention has shone on American evangelicals’ new prominence, less light has focused on a corresponding change in the nature of evangelicals. Case in point: Ted Haggard and the NAE.

The National Association of Evangelicals began during the Second World War, an era when evangelicals had lost much of their influence. Liberal theology was ascendant in many denominations and seminaries.

The NAE was formed for defense—to provide intellectual respectability and organizational counterweight. Its statement of faith, used by many organizations to this day, drew clear lines for scattered evangelicals to rally behind. This cross-denominational fellowship gave evangelicals representation with government agencies like the FCC, to give them more TV access, and with the military in its chaplain selection. Church leaders met at the NAE’s annual convention to compare notes and reinvigorate their relationships. The early NAE was almost entirely white, eminently respectable, deeply intellectual, and fervent in piety. It represented evangelicalism as it wanted to be seen: men in dark suits with advanced degrees. Evangelicalism’s rural, enthusiastic, anti-intellectual cousins were kept mainly out of sight.

During the 1980s and 1990s, evangelicalism changed from embattled minority to the most visible and vital sector of American Protestantism. Furthermore, evangelicals became a potent political force.

Haggard was elected president of the NAE in 2003, succeeding Leith Anderson, who saved the organization from a financial crisis that almost sank it. The financial difficulties were symptomatic of a deeper problem. Evangelicalism had changed, but the NAE had not. Its Washington office, led by Richard Cizik, had a growing insider’s voice in the political world. But to the larger world the organization had become, in Jack Hayford’s words, “a kind of an old men’s club.”

Haggard represents a new direction and a new kind of evangelical leader. He pastors an independent, charismatic megachurch. He has no advanced degrees. He rarely wears a suit and drives a pickup truck with a Napoleon Dynamite “Vote for Pedro” bumper sticker. He is ebullient, not cautious. The NAE has gained media attention with him in the spotlight.

When people describe Haggard, they grasp for words to express how sunny and optimistic he is. John Stevens, retired pastor of Colorado Springs’ First Presbyterian Church, told the Colorado Springs Gazette, “It’s really pretty hard not to like Ted Haggard. You can not like some of the things he does, or some of the things he might say on occasion, but it’s pretty hard not to like him personally.”

His celebrity may continue to grow, but Haggard believes only one cause is big enough and important enough to bring together today’s evangelicals—evangelism.

He laid out the case 10 years ago in Primary Purpose: Making It Hard for People to Go to Hell from Your City. If you want to make an impact on your city, he says, it’s not enough for one church or one denomination to do well. All the churches in the city need to do well. For 20 years in Colorado Springs he has pursued that point of view, working at building up all its “life-giving” churches, from whatever denomination. Through the NAE, Haggard hopes to accomplish at a national level what he has worked for in Colorado Springs—fostering a cooperative, active, outward spirit in all evangelical churches.

New Life’s Unusual Strategy

New Life’s building has all the grace and charm of a Super Wal-Mart, but its inelegant bulk is swallowed up by the vast open spaces of the Rocky Mountains. Across the valley, the Air Force Academy’s jagged, jet-age steel structures are clearly visible below the Front Range. Just down the road is the campus of James Dobson’s Focus on the Family. Dobson and he are good friends, Haggard says, though they lead with very different styles.

Focus on the Family has a tightly controlled corporate environment. Employees follow a strict dress code and would never let a reporter roam the campus unescorted.

If New Life had a dress code, it would include sports sandals and T-shirts. Weekday staff meetings for the 200 or so employees might be mistaken for a youth rally—or perhaps a Coors commercial, minus the beer. Pastors read the Scriptures from their BlackBerrys, and there is a high level of teasing, laughing, and applause among the staff, with Haggard leading the hijinks.

Haggard came to Colorado Springs in 1984, holding his first worship services in January 1985 in the unfinished basement of his home. He stacked three five-gallon buckets on top of each other for a pulpit and asked worshipers to bring their lawn chairs.

Raised in farm-town, church-attending Indiana, one of six children, Haggard was born again in high school while attending Campus Crusade’s Explo ’72. He followed up college at Oral Roberts University with a brief stint working for a West German Bible-smuggling organization. He then joined the staff of Bethany Baptist Church (now Bethany World Prayer Center) in Baker, Louisiana. He had been there for five happy years when his life’s calling came.

While on vacation in Colorado, Haggard camped alone on the slopes of Pike’s Peak for three days. Praying and fasting, he sensed a call to Colorado Springs. He promptly moved his family there.

The dramatic beginnings of New Life Church included visions and prophecies of future ministry. Haggard tells of satanic opposition, including anonymous death threats on the telephone and someone making cat-screeching noises from the field behind his home. There were anointings with oil—five whole gallons at one point—and cartwheels during worship. Growth was nothing short of spectacular. The church moved out of the basement in four months, and then inhabited a series of ever-bigger commercial sites before building their own facility in 1990. The current auditorium, dedicated in January of this year, seats 8,000 and has section numbers like a basketball arena.

Such a spectacular storyline is almost traditional for independent, charismatic megachurches, but New Life’s history includes some unusual notes. For one, Haggard was less interested in building a megachurch than he was in transforming a city. For another, he saw that he was not in competition with other churches. Quite the opposite: Competition between churches in Colorado Springs impeded him. Haggard means something fairly subtle by competition. For example, he picks a bone with a pastor who advertises his church’s “exciting services with practical, relevant Bible teaching.” According to Haggard, such a slogan really says, “My church is more exciting than the one you go to.”

Haggard’s publicly stated goal is that all “life-giving” churches in Colorado Springs grow. He urges each church, including his own, to keep their doctrinal specialties inside the walls of the church, while broadcasting a common-ground “mere Christianity” outside. New Life people strenuously avoid criticizing other Christians. Success, as they measure it, is not their own church’s attendance figures, but the total attendance at all of the churches in Colorado Springs.

Learning from Communist Society

Haggard is all about evangelism, but more than just evangelism. The New Life Church bookstore has a shelf marked “Pastor Ted Recommends.” Prominently displayed are books by culture warriors like Pat Robertson and Phyllis Schlafly, but also books by public-policy experts, historians, and analysts of secular culture like Dinesh D’Souza, Samuel Huntington, Bernard Lewis, Newt Gingrich, Thomas Friedman, and David Gergen. Yet we are in a church bookstore, where nearly all the titles are inspirational. Haggard is telling his congregation, Think big. Think about the whole world. The Bible does not tell you everything you need to know.

Haggard says he can pinpoint precisely where he learned to shift effortlessly from the religious to the secular. While a student at Oral Roberts University, he took a class entitled “Evangelicals and Communist Society.” He was particularly struck by unconfirmed tales of Albanian believers taken by police to the shores of the Adriatic Sea. The police stuffed the believers into barrels and then, while the victims’ families watched, floated the barrels into the water and took target practice.

“When I heard those stories I thought, What did those people pray in those barrels? They knew in a few seconds they were either going to be shot to death or shot up enough to drown. Could I invest my life to answer those prayers?

“What do you think they prayed? They prayed, ‘God protect my family. God take care of my little kids.’ How do you give them the best chance at having a good life? That became my clarion call: to make life better for people.

“It’s not hard. They need to live in a society where there’s freedom of religion. And if they want to gather up some wood and make chairs and sell them on the corner, they need to be able to do it. Free markets. Free markets have done more to help poor people than any benevolent organization ever has.”

But Jesus made no mention of free markets, Haggard is reminded. Jesus told the rich young ruler to sell all and give to the poor.

“But Jesus was in the 1st century,” Haggard answers, “and we’re in the 21st century.

“The Scripture is the Word of God, and nothing else is. But if the Scripture says we have an obligation to the poor, then you have to take what we’ve learned in the last 2,000 years to help poor people not to be poor. If the Scripture says we have an obligation to the oppressed, then you have to take what we learned in the last 2,000 years to help oppressed people. I maintain that we learned more about those subjects in the 20th century than in any other single century.”

Haggard is so enthusiastic about free-market economics that he applies it to church. New Life offers hundreds of small-group activities, everything from “Growing in God as a Wife and Mother” to “Holy Hip-Hop Jam Session.” How do the pastors decide what to include? They don’t. If someone comes up with an idea, and that person passes a basic screening, the church will help promote the group. New Life organizes the marketplace but leaves the details to the people, who write their own programs.

Gleeful Optimism

Haggard is a natural optimist in an evangelical culture that has sometimes tended toward pessimism about society. His fellow charismatics and Pentecostals, he says, often bemoan that there are no prophets in the modern world. He refers them to Bill Bright. ” ‘God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.’ Think about that. That was a major prophetic statement into his generation.

“You talk about optimism. I’m a depressed, narrow-thinking man in need of medication compared to Bill Bright. That’s in my spiritual genetics. Bill Bright is deep in me.” Haggard proudly displays a relay runner’s gold baton. Bill Bright gave it to him not long before his death, intending to confer on Haggard the responsibility for winning the world to Christ.

Haggard rejects the dispensationalism of The Late Great Planet Earth and the Left Behind novels. “There is no evidence that we should be anything but optimists,” Haggard says. “It was just three years ago that we were saying we support Israel because it’s the only democracy in the Middle East. And now there are potentially four: Lebanon, Afghanistan, Israel, and Iraq. Three are iffy, no doubt about it, but we can’t say Israel is the only one anymore.

“The trends of the last 40 years should make us optimistic. More people are living under representative government than ever before in history. More people’s civil liberties are protected than ever before in history. Women have greater opportunity than ever before in history. Fewer wars than ever before in history. We are really doing a good job of improving global economics and food distribution systems. The fact that [British Prime Minister] Tony Blair met with [religious leaders, including Haggard] to talk about the biggest aid initiative in world history, that’s good news.”

In Letters from Home, Haggard’s book of advice for his children, he tells of a word from God he had while watching a baseball game at summer camp. At one moment “the Holy Spirit came upon me and said, ‘If you will obey me, your life will work like this.'” Haggard watched as the team at bat began to hit every ball, scoring again and again. Then, “the Holy Spirit came on me again and said, ‘If you disobey me, your life will go like this.'” The team got few hits. Their opponents became formidable.

Earlier generations of Christians didn’t find life easy, Haggard acknowledges. Neither do Christians who live where faith is oppressed or where few opportunities exist. But for Christians in Colorado Springs, “I do not believe life is so hard. I think it is easy to live a good life.” Just when did you hear an evangelical leader say that?

Imperfect Consistency

“He thinks strategically, how to get things done,” says Ross Parsley, New Life’s worship leader and one of Haggard’s best friends. “He’s not a theoretician; he’s a practitioner.”

That’s a little maddening if you’re trying to locate a consistent philosophy. Haggard was once known for organizing spiritual warfare against territorial spirits. Now he’s known for free-market economics.

Haggard is a loyal member of the Religious Right who dials in for a White House conference call every Monday. Yet he embraces ecological concerns and says the Supreme Court made a good decision in the Lawrence v. Texas case, ordering the government out of the private lives of homosexuals.

Haggard thinks churches should keep their doctrinal distinctives to themselves, but he broadcasts political stands that some NAE members find objectionable. (When he produced a memo last spring listing “judicial restraint” at the top of the NAE’s priorities and “care for creation” at the bottom, the NAE board made clear they didn’t share his priorities.) Talking with Haggard, it isn’t entirely clear why politics should be argued in public, but doctrine shouldn’t.

Haggard isn’t searching for perfect consistency. He is attracted to what works. For him, everything seems to work these days. He loves to drop names of the politicians and journalists who have called. But he’s not stuck on politics. Should the political scene change and his influence wane, he would move on to the next thing.

In Haggard, one can see the new confidence of American evangelicalism. Previously consigned to the margins of respectable society, today’s evangelicals are on a roll. Those like Haggard enjoy their newfound influence and haven’t paused to sort out a philosophy of cultural engagement. They’re too busy making a difference.

But personality-driven and media-centric organizations don’t necessarily develop strong institutional foundations. Politicians are notoriously fickle. Today’s darlings are tomorrow’s has-beens.

And as the Bible amply warns, success is seductive. Haggard’s optimistic evangelicalism could become self-congratulatory religion-lite, baptizing the American way. It could turn evangelicalism into the church wing of the Republican Party. It could wrap free-market individualism around the Cross, confusing material wealth and personal happiness with spiritual riches. It could neglect the Cross altogether. The new evangelicalism that Haggard represents suffers such temptations, most obviously in the prosperity gospel.

What Is the Wealth For?

For Haggard, however, the ease and wealth of America is only a means to an end. “God’s salvation plan isn’t just about us,” he says. “God’s salvation plan is about us participating in his plan for the world. Thus, deny yourself, take up your cross, follow him.

“How do we respond to the people who are not persuaded by our message? We are responsible to make their lives better. Genesis 12 tells us that we are supposed to be a blessing to the world, even if they don’t respond. Maybe even especially if they don’t respond.

“We are responsible to help them, to serve them, to provide a community and a society and a culture that they can live in. That is the only way I can survive the concerns being raised now by secularists, that we may want a theocracy. I argue that’s not why we’re involved. We have a responsibility to serve everybody. Our own interests are not our interests, because we’re here for them.”

Such talk leaves doubters nervous. Theocrats often see themselves as beneficent. In Haggard’s case, the concern is muted by his love of dialogue, his enjoyment of difference, his genuine friendliness. He likes living in a pluralistic society. All he asks is a chance to speak his piece freely.

“We need to hear multiple voices in order to adjust our attitudes about things that are not absolutes,” Haggard says. “We shouldn’t shy away from discussions on substantive issues. We are citizens. We need to think and to let others think. We need the best ideas. We are the church. We have a responsibility to 6 billion people.”

Tim Stafford is a senior writer for CT.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Harper’s Magazine‘s piece on Ted Haggard, Soldiers of Christ is available online.

The Philadelphia Inquirer‘s Paul Nussbaum article on Haggard is also available online.

Haggard’s website has more info on his books, beliefs, and biography.

New Life Church offers mp3 sermons and more information for visitors.

The NAE website has more information about the organization, it’s government affairs office, and other news.

The Association of Life-Giving Churches, New Life’s church network, has the goal of seeing “churches, no matter their denomination, age or style of worship, promote and facilitate freedom of operation for the Holy Spirit.”

CT interviewed Haggard after his election as president of NAE:

Ted Haggard: ‘This Is Evangelicalism’s Finest Hour’ | The new president of the National Association of Evangelicals talks about the current state and future goals of the association and evangelicalism. (June 3, 2003)

Articles on our site by Haggard include:

Decalogue Debacle | What we can learn from a monument now locked in an Alabama closet. By Ted Haggard (April 12, 2004)

Life vs. Law | Your preaching can inspire graceful or grudging obedience. by Ted Haggard, from Leadership Journal, Fall 2002