Jackie Roberts drove a carload of kids from Florida to a cornfield in the Midwest out of motherly love and because her son wouldn’t stop bugging her. After six months of pestering, 15-year-old Brock convinced her that this was the only place he could see his favorite Christian bands. Over 1,000 miles later, Roberts wasn’t so sure about the Cornerstone Festival.

Not far from where Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri meet, Roberts, her three kids, a niece, and Brock’s best friend passed through Bushnell, Illinois, a quaint farm town of 3,221. Further down a dirt road, they entered the festival gates and the rural scenery changed drastically. The entire car fell silent.

This wasn’t the contemporary Christian music scene they expected. Inching through the bustling and dirty festival grounds, the Roberts group—except for an ecstatic Brock—gasped as they passed lines of hippies, punks, Goths, brightly colored Mohawks, and lots of tattoos.

Staring at a half-naked man in a dog collar, Jackie’s oldest daughter asked Brock, “What have you gotten us into?”

‘The Cacophony Doesn’t Bother Them’

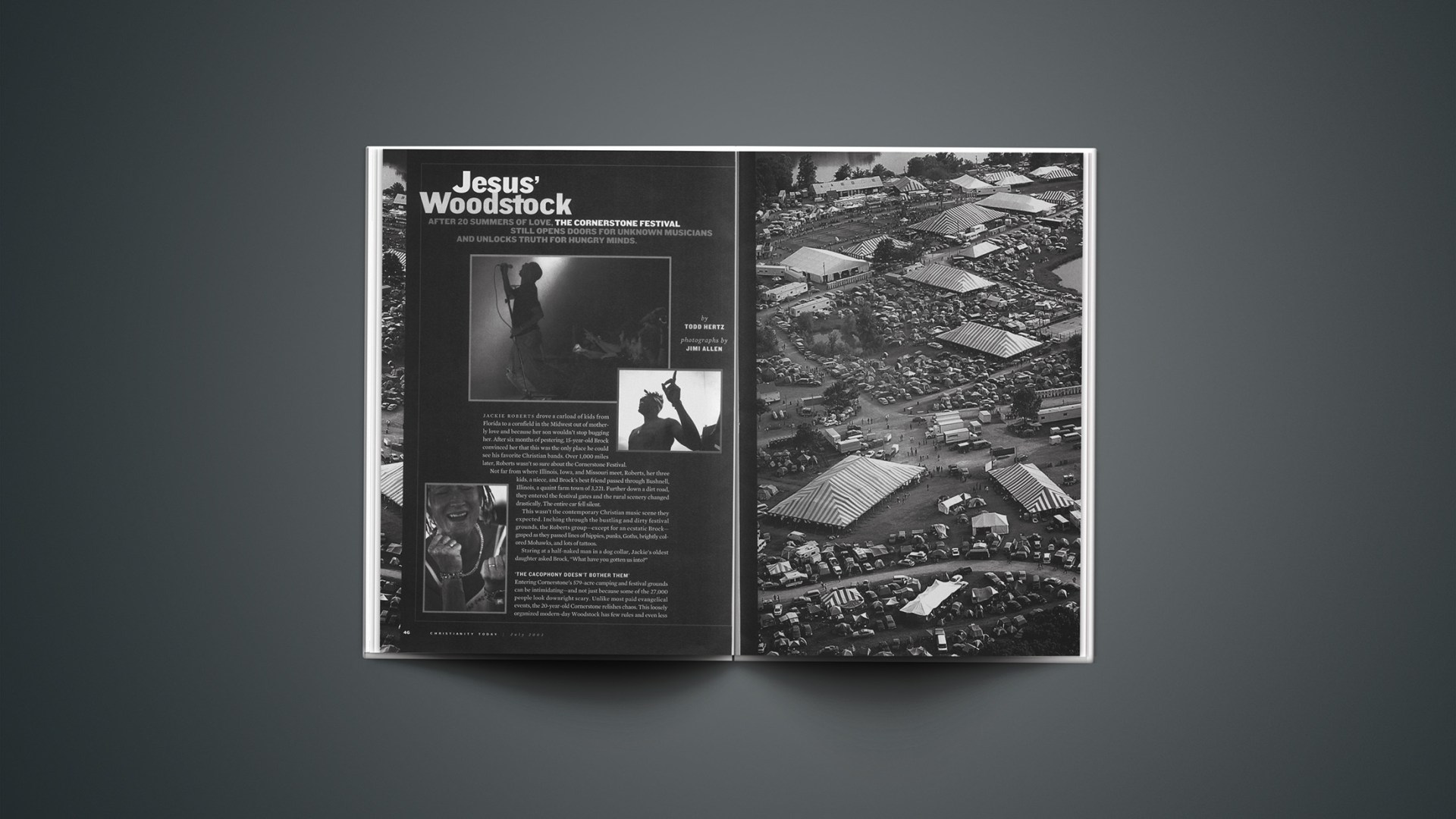

Entering Cornerstone’s 579-acre camping and festival grounds can be intimidating—and not just because some of the 27,000 people look downright scary. Unlike most paid evangelical events, the 20-year-old Cornerstone relishes chaos. This loosely organized modern-day Woodstock has few rules and even less signage to help you know where you are or what is happening.

The July festival’s stock in trade is stimulus overload. Loud music is constant and the visual stimulation is dizzying. All festivals offer multiple events and activities. Cornerstone does them all at once and constantly for five days. Three hundred bands play 11 stages from late morning to early the next morning. Simultaneously, there are sports competitions, a film festival, a dance tent, an art gallery, the children’s Creation Station, and 250 hours of seminars.

This constant and often overwhelming activity, like the festival’s identity itself, is a reflection of who throws the party: Jesus People U.S.A. (JPUSA). The 500 members of this intentional community, which is affiliated with the Evangelical Covenant Church, live in an old Chicago hotel they call Friendly Towers.

“In a small town, you have a family with a story in every house,” says Linda Lafianza, cofounder of Christian pop-culture webzine, The Phantom Tollbooth. “But in an urban area, you have four dramas on a floor. This is why the cacophony doesn’t bother them; they are used to chaos, ambiguity, and everything happening at once.”

Festivalgoers show up days before Cornerstone starts. Crowds swell around campsites-turned-stages where people put on their own shows with dad’s power generator and an amp. Campsites, cars, and a surprising number of VW microbuses stake out what space on the 180 acres is not lake or dense woods. Some people pitch tents only feet from blaring music stages; others don’t camp as much as eventually lie down in the dirt.

“I was totally blown away by what I saw,” says Jackie Roberts, who has returned to Cornerstone twice—even without Brock. “I was expecting all young, preppy, youth group kids. The diversity at first was intimidating, but it ended up being an incredible blessing. I saw youth groups. I saw punks. I saw grandmas. I saw families with babies. With 27,000 diverse people loving each other, you know God is there.”

Cornerstone is neither America’s largest Christian festival nor the oldest. In fact, most Christians may have no idea it exists. A constant wall of sound and kids with rings and studs piercing their faces is not everyone’s idea of fun. As founding director Henry Huang says, “Cornerstone tends to attract a certain temperament.”

But there is a method to the madness. Cornerstone may come dressed in an anything-goes attitude and pink hair spikes, but it’s actually a fine balance of liberal self-expression and conservative, evangelical theology.

“To me, Cornerstone looks like an event run by a bunch of old hippies, modern young people, and musicians rather than church leaders, businessmen, and conservatives,” says current festival director John Herrin. “JPUSA itself has always been a funny bunch and probably a dichotomy. We look like the biggest bunch of liberals but live and believe a lot more conservatively than a lot of conservatives. This is how Cornerstone’s culture reflects us. We don’t care if kids stay up too late, make too much noise, and dress wild. In fact, we enjoy it. But we believe in the Bible literally and want these same kids to be grounded biblically and live in a godly fashion.”

America’s Last Jesus Fest

Cornerstone began in 1984 with many of the same ideals that drew thousands of countercultural youth into the Jesus movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s: community, acceptance, musical appreciation, and spiritual intensity. “Cornerstone keeps us connected with those first moments of conversion when we realized Jesus was a way cool hippie, the coolest hippie,” says Lafianza, whose Phantom Tollbooth works with the festival in public and press relations. “God didn’t keep us like that for long. He gave us the urge to wash our clothes, straighten up, and no longer need the things that defined that lifestyle. Cornerstone is a touchstone for evangelicals who put away childish things.”

According to Randall Balmer’s Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism, most of the movement’s “Jesus people” eventually assimilated into mainstream evangelicalism. There were an estimated 600 Jesus communes in 1971. Few now survive. When the Jesus People of Milwaukee broke up in 1972, their traveling evangelism team was touring the country, distributing Cornerstone magazine and staging concerts by their rock & roll group, Resurrection Band. When their bus broke down in Chicago, they made the Windy City home. To support the expense-sharing community, JPUSA established numerous companies. It also founded several ministries, including a free food pantry, a homeless shelter, and a crisis pregnancy center.

Meanwhile, Rez Band continued playing churches and a dwindling number of Jesus festivals, the movement’s answer to Woodstock. By the early ’80s, however, JPUSA felt these events had turned shallow and were tainted by commercialization.

“Due to tremendous church resistance to rock music and other cultural forms of expression, [festival] promoters favored ‘safe’ middle-of-the-road CCM performers over the increasing number of innovative Christian rock bands,” writes Jon Trott, editor of Cornerstone, in an article on JPUSA’s history. “In addition, festival teachers sometimes seemed to be chosen more for their drawing power than their power to minister.”

If they couldn’t find the festival they were looking for, JPUSA members reasoned, they would start it. They had little experience in event planning (director Huang helped form Britain’s Greenbelt Festival), but set three non-negotiables for their vision. First, bands could play the fest regardless of their marketability as long as their members were believers. Second, seminars would be weeklong classes on in-depth topics, not the one-hour talks of many events. Third, Trott wrote, Cornerstone would be “a bridge between young, culturally radical believers and older, culturally ‘straight’ believers.”

In the last 20 years, Cornerstone has established itself in these areas. This last major American Jesus festival has become a successful outreach to countercultural youth, Christianity’s largest and most influential gathering for cutting-edge music, and an unlikely center of theological training and discussion.

‘Christians Can Do that?’

“There are elements that make this feel like a Christian Woodstock—brotherly love and caring for each other,” says festival director Herrin. “But what comes out of that is a presentation of the gospel that is more understandable to your postmodern kid on the fringe. I know a lot of kids who would not step a foot in the door to bigger, more conservative events. Cornerstone reaches kids who are more interested in what [secular heavy metal band] Korn’s new album sounds like than what Michael W. Smith is doing.”

JPUSA members’ experience in fringe outreach comes from their own Jesus Movement conversion stories. Their blueprint is simple: be honest and make the gospel culturally relevant. “In ministry, it is important to stay true to who you are,” Herrin says. “It is obvious to kids if you are pretending. Don’t put together a festival of bands you would never listen to. When I was 17 years old, what helped me embrace the gospel was meeting a bunch of young Christians with hair down to the middle of their backs who were playing rock & roll. I thought, ‘Christians can do that?’ “

JPUSA’s passion for the arts is the major draw for countercultural youth. But the festival, unlike what many festivalgoers say they find in the church, is also an accepting community. “I grew up in a conservative church where I always felt like an oddball,” says Melissa May Blair of the band Madison Greene. “I had to defend myself for having a tattoo or burning incense. It’s nice to find a place where people understand you. You can find that elsewhere, but they won’t have your connection to Christ.”

Maintaining this comfortable environment for non-Christians or the disenfranchised while proclaiming the gospel is a fine line. “I don’t want the gospel to be watered down where this becomes just another fun, happy camping blowout weekend,” Herrin says. “We don’t believe in mushy truth.”

The festival is designed for relationship evangelism within a supporting community. Not every band or speaker will make an altar call or directly preach salvation, but JPUSA believes the gospel will find a way. “The message will be there,” Herrin says. “But this is a place seekers can come to find truth, regroup with solid Christians, or not be scared off by Christian lingo. There are a lot of ways to see the truth. Perhaps they will hear the gospel in a seminar, from a band, or see it in a picture.”

JPUSA deliberately leaves gaps in Cornerstone’s logistics and policing. Herrin says the fest’s defining feature is freedom in Christ. JPUSA considers festivalgoers partners and relies on the honor system. Cornerstone’s only real rules prohibit fireworks, drinking, and drugs. Last year was the first fest with a nightly curfew. “We take an enormous risk,” Herrin says. “We have people do some silly things. It’s worth it, though, to have an event that is a little more free and a little more fun.”

Jim Owens, a retired state police officer, was part of a Bushnell group that met with JPUSA when the fest moved there in the early ’90s. He says that while the town was slightly worried at first, there have been fewer than 10 arrests since. There are times when you will smell marijuana smoke. Most other incidents at Cornerstone fall under the category of “stupid things unsupervised teenagers do.”

Gabriel Wilson, a singer for the band Rock & Roll Worship Circus, says that in any Christian subculture, members will push the limits of grace in order to find their identity. Other observers say that besides providing an accepting Christian environment to youth who feel outside the church, Cornerstone also leaves room for kids to act out or try countercultural behaviors and fashions. Wilson says that the fest’s identity gives it a different code of ethics.

“Cornerstone is the only Christian music festival where a guy can light up a cigarette or spout four-letter words and no one thinks anything of it,” says Wilson, who has played the fest twice. “Of course, Cornerstone doesn’t condone these behaviors and JPUSA doesn’t practice them, but it also doesn’t have rules forbidding them like other fests do.”

In regulating behavior, Cornerstone draws the line at essentials. “We feel people have decent common sense so we only focused on elements of safety and biblical rights and wrongs,” says Huang, who now works for Wycliffe Bible Translators. “But it is an issue they continue to wrestle with. Cornerstone has had to deal with some security, safety, and liability problems. People have been hurt physically and spiritually. These things are normal for any major event, but particularly so for something so laissez-faire as Cornerstone.”

The Christian Music Thrift Store

A prominent worship singer once played Cornerstone only weeks after appearing at Creation Fest, the nation’s largest mainstream CCM festival (Creation’s two locations draw annual crowds near 95,000 and feature 50 of Christian radio’s top artists). After her set, the performer told festival staff: “If Creation is the Gap, Cornerstone is the thrift store.”

CCM and Nashville are practically dirty words at Cornerstone. Many festivalgoers won’t even approach the main stage, which the well-known names usually play. Instead, most excitement occurs in hot, smelly tents at midnight. Bands that sell fewer than 3,000 albums a year are legends in Bushnell.

“I have always felt that at other festivals, the smaller or independent bands without radio play get the shaft,” says Blair of Madison Greene, a “tribal” group that plays a blend of African, Celtic, and Native American music. “You don’t get respect and people are not conscious of you. But there is equality and respect at Cornerstone that is not elsewhere because it’s a fest put on by musicians.”

With the festival’s loose criteria for bands—they’re good and they’re believers—the playbill is eclectic. In one night you can hear punk, blues, heavy metal, ’60s rock, bluegrass, Peruvian pan flute, and music that really has no definition. Bands range from pioneers of Christian music to groups that haven’t played beyond their parents’ garage. Many acts are popular in the CCM or mainstream markets but either grew up at the fest or are considered edgy enough to be hip. Some bands only get together for Cornerstone. Others won’t play any other Christian venue.

Critics argue that band selection is too open. Some bands tour with controversial secular acts like Limp Bizkit, Offspring, and Marilyn Manson. Festivalgoers voiced concern last year when Pedro the Lion—whose album, Control, critically depicts adultery with some explicit language—was booked for the main stage.

“The artists we look for are ones with a connection to the faith despite whether they feel they are evangelists,” says Herrin, Rez Band’s former drummer. “We have many for whom this is the only Christian event they’d consider. They do it because they feel they won’t be scrutinized here. No one is going to ask them how many kids got saved last year. We believe God brings some bands for their own good. Maybe they have a bad taste in their mouths and need to see Christians in a new light.”

Of course, this is not a stellar business model. “The greatest strength of Cornerstone is that it was allowed to develop over time,” says Huang. “It lost incredible amounts of money for many years. It was supplemented and supported essentially as a ministry outreach by the community. That situation gave Cornerstone the ability to develop impervious to the market forces or economic return.”

The festival has now become self-supporting, Herrin says, but has never been considered a moneymaker. He said Cornerstone wouldn’t have made a dime if staff weren’t JPUSA members, who are not paid salaries but receive stipends.

By giving a national stage to music that wouldn’t have stood a chance in the CCM market, Cornerstone has changed the Christian industry by creating a need for more alternative venues, labels, and markets. Brandon Ebel, founder of Tooth & Nail Records, has credited being a “Cornerstone kid” with influencing him to form what is now the country’s largest edgy and progressive Christian label. Observers consider Cornerstone an indicator of what will next be big in the overall Christian industry.

Perhaps Cornerstone’s biggest musical legacies lie in the stories of individual bands. Sixpence None the Richer, MxPx, and Third Day grew up here. Christian artists including the 77s, Adam Again, The Choir, and Daniel Amos have all said they couldn’t have lasted without Cornerstone. Others—like Larry Norman and Randy Stonehill, Stryper, Altar Boys, and White Cross—have reunited in Bushnell.

Mainstream superstars P.O.D. began on the New Band Stage. Others have been signed playing in their own campsites. “I don’t think there is another place where an unheard-of band can come away from having played for thousands of kids,” says Tooth & Nail’s Johnson. “Overnight, they have an instant fan base.”

It is mind-boggling that a festival known for loud, raucous, and off-center music could also be the home of serious theological education. “Of course, this is not a really comfortable learning environment,” says Jay Phelan, dean of North Park Theological Seminary and a two-year teacher at the fest. “It’s hot and you’re sitting in a tent near a band that sounds like someone playing a guitar with a cat.”

“Cornerstone U” classes range from social justice to apologetics and from dispensationalism to parenthood. Every year the fest attracts top Christian theologians such as Norman Geisler and Stanley Grenz and ministry leaders like John Perkins and Clive Calver.

“They are engaging modern culture with the gospel in ways I don’t see many groups doing,” says Mimi Haddad of Christians for Biblical Equality. “I am a member of the Evangelical Theological Society, and I am telling you, Cornerstone can hold its own. It’s a place for irenic dialogue, a place to think rigorously, and a place where no one agrees on much.”

The mode of presentation usually involves analyzing the various sides of a hot issue. “We want this to be a place where people come to seek the truth and debate about it,” Herrin says. “We aren’t some liberal hotbed where any goofy theory is given equal footing, but it is a place where we can talk about any number of things and look at all sides of the discussion.”

JPUSA is much more selective in programming Cornerstone U, Herrin says, than in who it allows to play a stage. “We want assurance we can vouch for them,” he tells CT. “We might not agree with them, but we ensure they have a point of view that is biblically based and can be defended as such.”

‘Christian Pilgrims’

What often impresses speakers is not that there is such heady, in-depth learning happening at Cornerstone but the seriousness with which festivalgoers take it. With about 10 sessions happening at once, most still draw audiences of more than 50 who stay with their courses for the week.

“I get to speak in a lot of churches and venues, but there is no place like Cornerstone to encourage me about the coming generation,” says Elliot Miller of the Christian Research Institute. “Hundreds of young people travel across the country and live in tents to spend their days in lectures on really heady, intellectually challenging Christian material. And they just eat it up. They ask engaging questions. They line up to continue the discussions with me afterward.”

Haddad, who spoke at Cornerstone for the first time last year, was shocked by the scholarship of festivalgoers. People gather materials, study them overnight, and return to discuss what they learned. A 17-year-old woman studied from a Greek New Testament. A young man carried the entire works of archaeologist W. F. Albright on his laptop.

“This is a group of Christian pilgrims,” Haddad told CT. “They are not settled into their opinions; they want to continue to explore, learn, and debate. You are going to find your leaders of tomorrow from this group. How many 17-year-olds read the Greek Bible?”

That this studious young woman is at a fest with bands called One Bad Pig and Noise Ratchet illustrates the balance struck at Cornerstone. But such a delicate balance and loosely organized structure may not last forever.

“It started out as a big party and every year it continues is a miracle,” says Phantom Tollbooth’s Lafianza. “There are simply some aspects to it that just are not permanent.”

In the meantime, Cornerstone is expanding. This spring and summer, JPUSA has launched two-day festivals in both Florida and North Carolina. “I found this move astounding since these guys are so loosey goosey,” says Phil Olson, a vice president with Evangelicals for Social Action, who has spoken at four Cornerstone festivals. “Cornerstone organizers don’t return e-mails, they don’t call you back, but now they are adding two more events? I’m amazed.”

Todd Hertz is

Christianity Today

‘s online assistant editor.Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

The official Cornerstone site covers the festival live as well as posts concert schedules, seminars, and other information for all three 2003 festivals.

The JPUSA website has more information on the community including a full history written by John Trott. An entire chapter of the account focuses on the birth and development of the Cornerstone Festival.

Cornerstone Magazine is available online. A current article tells the “unofficial story” of the festival.

More information about The Phantom Tollbooth, Creation Festival, and the Greenbelt festivals is available at their respective websites.

Christianity Today‘s earlier articles on Cornerstone and Jesus People U.S.A. include:

Stryper Returns to Play the Festival They Always Should Have | Cornerstone Music Festival takes a look back at artists who paved the way. (July 12, 2001)

Come for the Music, Stay for the Worship | Diversity in artists, worship and people last through 18 years of the Cornerstone Festival. (July 6, 2001)

Weblog: Chicago Tribune Investigates Jesus People USA (Apr. 3, 2001)

Conflict Divides Countercult Leaders | A 1994 Christianity Today article reports on the conflict between sociologist Ronald Enroth and JPUSA. (July 18, 1994)

Jesus’ People | Lessons for living in the “we” decade. (Sept. 14, 1992)