Maimuna Barkad, 21, entered a grocery store in Mogadishu, Somalia, in June 1991 to buy food for her parents and 11 siblings. She has not seen them since. “Bombs started exploding,” Barkad told Christianity Today. “The people at the store told me not to go home, that I would be killed. They told me to start running.”

She ran, and then walked, with three other refugees for three months—homeless, hungry, thirsty, and tired. As the refugees crossed a river into Kenya in small, makeshift boats, one of the crafts sank, drowning two of her companions.

After a year in refugee camps, Barkad found a safe haven in the United States with the help of the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program. She later received help from World Relief, an evangelical relief agency. Barkad, a Muslim, settled in the Atlanta area, married, and had two children.

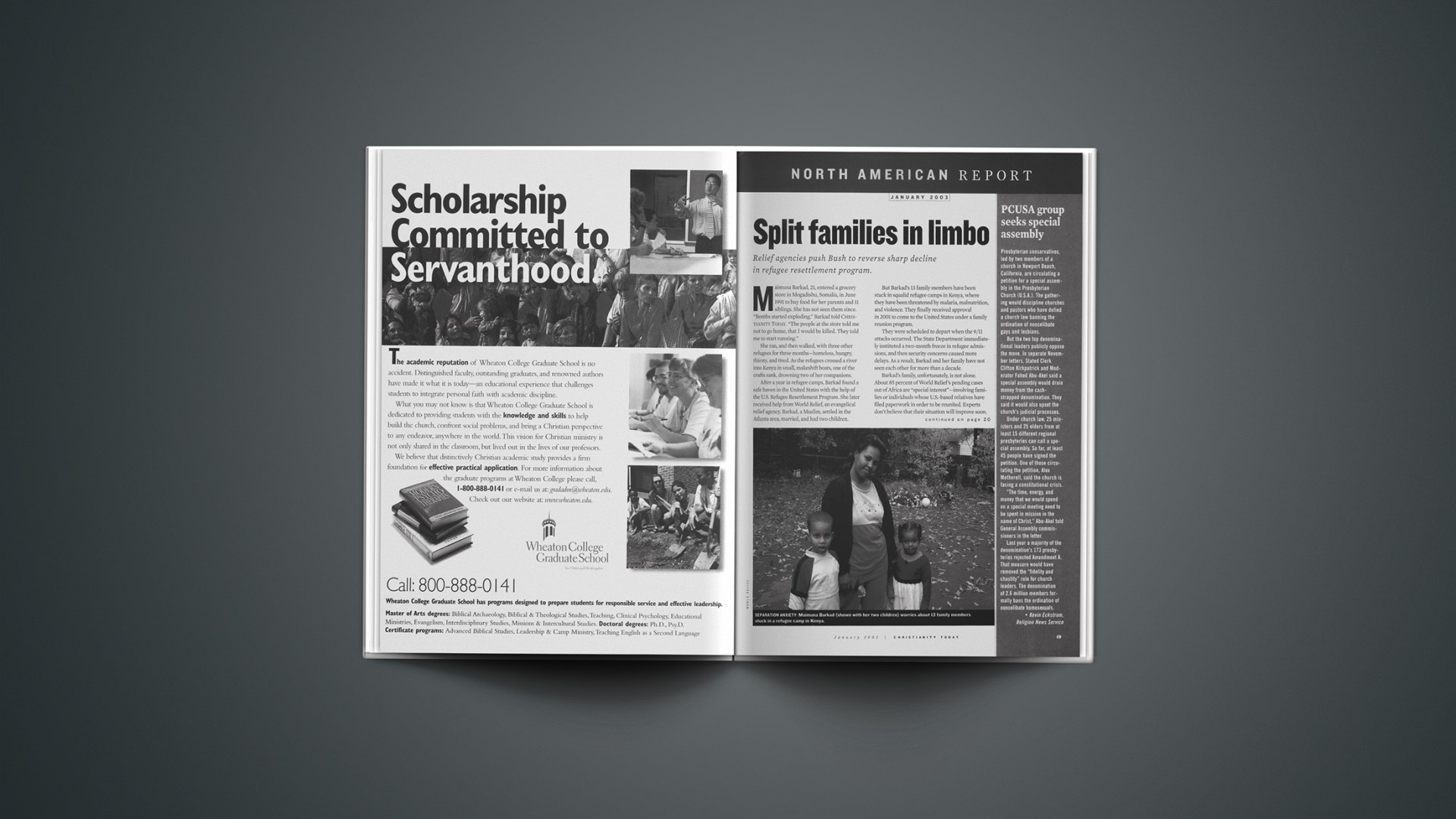

But Barkad’s 13 family members have been stuck in squalid refugee camps in Kenya, where they have been threatened by malaria, malnutrition, and violence. They finally received approval in 2001 to come to the United States under a family reunion program.

They were scheduled to depart when the 9/11 attacks occurred. The State Department immediately instituted a two-month freeze in refugee admissions, and then security concerns caused more delays. As a result, Barkad and her family have not seen each other for more than a decade.

Barkad’s family, unfortunately, is not alone. About 85 percent of World Relief’s pending cases out of Africa are “special interest”—involving families or individuals whose U.S.-based relatives have filed paperwork in order to be reunited. Experts don’t believe that their situation will improve soon.

On October 16, the Bush administration announced new and tighter restrictions on admissions of refugees (people displaced outside their home countries). It doesn’t look bad on paper. The guidelines allow for up to 70,000 refugees to enter this county, the same as last year. But 20,000 slots are designated as “unallocated reserve,” meaning the government is not likely to admit those 20,000, except in extraordinary circumstances. Refugee advocates liken this reserve to “unused lifeboats.”

Lowest in 22 years

Furthermore, refugee advocates say the U.S. government will admit no more than 50,000 refugees through the end of this fiscal year, which ends in October. But even that projection may be optimistic. Although the administration authorized 140,000 refugees during the past two years, no more than 78,000 have been admitted.

The United States resettles more of the world’s 12 million refugees than does any other country. According to the United Nations, America resettled 68,400 refugees in 2001, followed by Canada (12,200), Australia (6,500), Norway (1,300), and Sweden (1,100).

But World Relief said the U.S. admission numbers for the last two years are the lowest in the 22-year history of the program. “President Bush has turned his back on refugees,” said Galen Carey, director of advocacy and policy for World Relief. “[It] is one of the most mystifying failures of this administration. It is unconscionable to allow even one refugee to die unnecessarily in a refugee camp when we have the capacity to help.”

Advocates point out that many refugees have been victims of religious persecution—though this is sometimes difficult to prove. “I am not aware of any reliable statistics on the numbers of refugees fleeing religious persecution, or how many of those would be Christians,” said John Arnold of World Relief’s Atlanta office. “In many cases, such as Sudan or Bosnia, religion is intertwined with race, culture, tribe, and ethnicity.”

Refugee advocates and politicians, including Senators Orrin Hatch, Edward Kennedy, Sam Brownback, and Bill Frist, are asking Bush to help those refugees in limbo because of security concerns. In October, Brownback, R-Kansas, introduced the North Korean Refugee Relief Act of 2002. It would solve a technical problem that inhibits American assistance, Brownback said.

Fraud allegations

Refugee advocates recommend that the Bush administration authorize 100,000 refugee admissions to make up for last year’s shortfall. But that’s unlikely without fundamental changes in the program, according to a September report to Congress.

The Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (BPRM) reported that more lengthy background checks and other factors have dramatically slowed processing time. “We must first recover from the setbacks of [fiscal] 2002 before we can grow the program,” the bureau said.

The bureau said new security procedures enacted since 9/11 play a role in the decline. The report also said the Immigration and Naturalization Service (ins) has discovered fraud or misrepresentation in 40 percent of approved family reunion cases. (Resettlement programs attempt to expedite family reunion.)

But World Relief’s Carey said that alleging fraud is a weak excuse for lowering refugee admissions ceilings, adding: “The response to fraud should be to improve verification standards.”

Carey said a significant number of fraud allegations concerned legitimate refugees who claimed a closer relationship to family in the U.S. than really existed.

Aside from the 9/11 attacks, achieving refugee admission status is a lengthy exercise. First, a United Nations agency or a U.S. Embassy must refer a person to the BPRM. The bureau then decides whether the applicant meets the State Department’s established criteria for refugee status. To qualify, a person must be persecuted, or be in danger of persecution, because of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. The bureau then presents the applicant’s case to the ins for screening. The ins links an approved refugee with a resettlement organization.

Nonprofit agencies help with practical matters, such as finding a home and a job. Among the 10 agencies authorized by the Department of State to resettle refugees, only World Relief is evangelical. Working with evangelical churches and volunteers, the agency has resettled 180,000 refugees from 30 countries in 27 communities since 1978—up to 10,000 per year.

World Relief helped Barkad, who has a work permit but is not a U.S. citizen. After working as a travel agent, she is now studying to be a respiratory therapist.

There are many other success stories. A former military officer from Vietnam told his resettlement story to ct, provided he was not named. Vietnamese communists had sent the officer to a re-education camp. He escaped by boat, and a Malaysian navy ship rescued him. The United States eventually admitted him as a refugee. He is now a Christian who helps other refugees.

Back in the refugee camp in Kenya, the waiting continues. Barkad doesn’t know what more she can do. “They were already approved,” Barkad said. “I don’t understand it.”

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

The official presidential determination on refugees is available online at the White House site.

An in-depth article of the restrictions is online at the site of the U.S. Committee for Refugees.