“It is only reasonable to think that matter for praising God should be taken from the sea, which is fraught with so many wonders.” — John Calvin, Commentary on Psalm 148

On a rare, warm day in mid-March, when back in New Hampshire the snow was melting into mud, and in Boston, everyone else was strolling along the harbor or sitting on benches licking ice cream cones, I quit the blessed sunlight for the moist, dim sanctuary of the New England Aquarium. I had a date with a giant Pacific octopus.

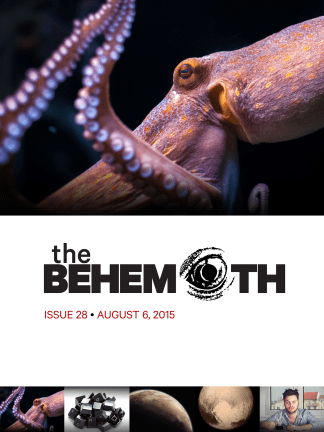

Her name was Athena, but I didn’t know that then. I knew little about octopuses—not even that the correct plural is not octopi, as I had always believed (it turns out you can’t put a Latin ending—i—on a word derived from the Greek, like octopus). But what I did know intrigued me. Here is an animal that has venom like a snake, a beak like a parrot, and ink like an old-fashioned pen. It can weigh as much as a man and stretch as long as a car, yet can pour its baggy, boneless body through an opening the size of an orange. It can change color and shape. It can taste with its skin. Most fascinating of all, I had read that octopuses are smart. This bore out what scant experience I had already had; like many who visit octopuses in public aquaria, I’ve often had the feeling the octopus I was watching was watching me back, with an interest as keen as my own.

How could that be? It’s hard to find an animal more unlike a human than an octopus. They have no bones. They breathe water. Their bodies aren’t organized like ours. We go: head, body, limbs. They go: body, head, limbs. Their mouths are in their armpits—or, if you prefer to liken their arms to our lower, instead of upper, extremities, between their legs. Their appendages are covered with suckers, a structure for which no mammal has any analog.

And not only are octopuses on the opposite side of the great vertebral divide that separates backboned creatures like mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish from everything else; they are classed within the invertebrates as mollusks, like slugs and snails and clams, animals who are not particularly renowned for their intellect. Clams don’t even have brains.

The lineage that would lead to octopuses and the one leading to humans separated more than half a billion years ago. Was it possible, I wondered, to touch another mind on the other side of that divide?

Octopuses represent the great mystery of the Other. They seem completely alien, and yet their world—the ocean—comprises far more of the earth (70 percent of its surface area; more than 90 percent of its habitable space) than the land.

Most animals on this planet live in the ocean. And most of them are invertebrates like Athena.

That was why I wanted to meet the octopus. I wanted to touch an alternate reality. I wanted to explore a different kind of consciousness, if such a thing exists. What is it like to be an octopus? Is it anything like being a human? Is it even possible to know?

So when the aquarium’s director of public relations, Tony LaCasse, met me in the lobby, and offered to introduce me to Athena, I felt like a privileged visitor to another world. But what I began to discover that day, after half a century of life on this earth, and much of it as a naturalist, was my own, sweet, blue planet—a world breathtakingly alien, startling and wondrous, a world in which I would at last feel fully at home.

***

Tony tells me that Athena’s lead keeper, senior aquarist Bill Murphy, isn’t in. My heart sinks; not just anyone can open up the octopus tank, and that’s for good reason. A giant Pacific octopus—the largest of the world’s 250 or so octopus species—can easily overpower a person. Just one of a big male’s three-inch-diameter suckers can lift 30 pounds, and a giant Pacific has 1,600 of them. Also, octopuses can bite, and they can inject a neurotoxic venom, as well as saliva with the ability to dissolve flesh. Worst of all, they can take the opportunity of an open tank to escape, and an escaped octopus is a big problem for both the octopus and the aquarium.

Happily, Tony finds another senior aquarist who is familiar with octopus to help me. Scott Dowd, a big guy in his early 40s with a silvery beard and twinkling blue eyes, is the senior aquarist for the Freshwater Gallery down the hall from Cold Marine, where Athena lives. Scott first came to the aquarium in diapers on its opening day, June 20, 1969, and basically never left. He knows almost every animal in the aquarium personally.

Athena, Scott explains, is about two and a half years old, and weighs about 40 pounds. He lifts the heavy lid covering her tank. I mount the three short steps of a small moveable stair and lean over to see. She stretches about five feet long. Her head—by “head,” I mean both the actual head and the mantle, or body, because that’s where we mammals expect an animal’s head to be—is about the size of a small watermelon. “Or at least a honeydew,” says Scott, staying with the fruit theme. “When she first came, it was the size of a grapefruit.” The giant Pacific octopus is one of the fastest-growing animals on the planet. Hatching from an egg the size of a grain of rice, one can grow both longer and heavier than a man in three years.

By the time Scott has propped the tank cover open, Athena has already oozed from the far corner of her 560-gallon tank to investigate us. Still holding to the corner with two arms, she unfurls the others, red with excitement, and reaches to the surface. Her white suckers face up, like a person extending a palm for a handshake. “May I touch her?” I ask Scott. “Sure,” he says. I take off my wrist watch, remove my scarf, roll up my sleeves and plunge both arms elbow-deep into the shockingly cold, 47°F water.

Twisting, gelatinous, her arms boil up from the water, reaching for mine. Instantly both my hands and forearms are engulfed with dozens of soft, questing suckers.

It occurred to me later that not everyone would like this. The naturalist and explorer William Beebe found the touch of the octopus repulsive. “I have always a struggle before I can make my hands do their duty and seize a tentacle,” he confessed. Victor Hugo imagined such an event an unmitigated horror leading to certain doom. “The spectre lies upon you; the tiger can only devour you; the devil-fish, horrible, sucks your life blood away,” Hugo wrote in Toilers of the Sea. “The muscles swell, the fibres of the body are contorted, the skin cracks under the loathsome oppression, the blood spurts out and mingles horribly with the lymph of the monster, which clings to the victim with innumerable hideous mouths.…” Fear of the octopus lies deep in the human psyche. “No animal is more savage in causing the death of man in the water,” Pliny the Elder wrote in Naturalis Historia, circa AD 79, “for it struggles with him by coiling round him and it swallows him with sucker-cups and drags him asunder…”

But Athena’s suction is gentle, though insistent. It pulls me like an alien’s kiss. Her melon-sized head bobs to the surface, and her left eye—octopuses have a dominant eye, as people have dominant hands—swivels in its socket to meet mine. Her black pupil is a fat hyphen in a pearly globe. Its expression reminds me of the look in the eyes of paintings of Hindu gods and goddesses—serene, all-knowing, heavy with wisdom stretching back beyond time.

“She’s looking right at you,” Scott says.

As I hold her lidless, silvery gaze, I instinctively reach to touch her head. “Supple as leather, tough as steel, cold as night,” Hugo wrote of the octopus’s flesh; but to my surprise, her head is silky, and softer than custard. Her skin is flecked with ruby and silver, a night sky reflected on the wine-dark sea. As I stroke her with my fingertips, her skin goes white beneath my touch. Later, I learn this is the color of a relaxed octopus; in cuttlefish, close relatives of octopus, females turn white when they encounter a fellow female, someone who they need not fight or flee.

It is possible, I later learn, that Athena, in fact, knows I am a female. Though octopuses can taste with all their bodies, this sense is most exquisitely developed in the suckers. Hers is an exceptionally intimate embrace: she is at once touching and tasting my skin, and possibly the muscle, bone and blood beneath. Female octopuses, like us, possess estrogen; she could be tasting and recognizing mine. Though we have only just met, Athena already knows me in a way no being has known me before.

And she seems curious to know more—as curious about me as I am about her. Slowly, she is transferring her grip on me from the smaller, outer suckers at the tips of her arms to the larger, stronger ones, nearer her head. I am now bent at a 90 degree angle, folded like a half-open book, as I stand on the little stepstool. I realize what is happening: she is pulling me steadily into her tank.

How happily I would go with her! But alas, I know I would not fit. Her lair is beneath a rocky overhang, into which she can flow like water, but I cannot, constrained as I am by bones and joints. The water in her tank would come to chest-height on me, if I were standing up; but the way she is pulling me, I would instead be upside down, head first in the water, and soon facing the limitations of my air-hungry lungs. I ask Scott if I should try to detach from her grip. Gently he pulls us apart, her suckers making popping sounds like small plungers as my skin is released.

Sy Montgomery is the author of 20 books for adults and children on animals, nature, and the environment.

From The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery. Copyright © 2015 by Sy Montgomery. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Epigraph added by The Behemoth’s editors.